Introduction

Long before journals, and digital object identifiers (DOIs), science was shared in ink and wax. Letters were the vessels of discovery between natural philosophers. Galileo writing to Kepler, Darwin sending drafts to Hooker, Émilie du Châtelet debating Newtonian physics with Voltaire, or Marie Curie exchanging ideas with Albert Einstein. The 17th-century Philosophical Transactions wasn’t just a repository of findings; it was the latest evolution of a timeless question: how should scientists communicate?

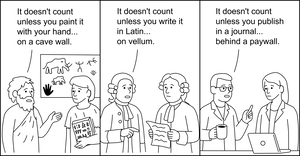

From handwritten correspondence to conferences, from lab notebooks to preprints with living analyses (e.g.1), scientific publishing has never been static. It has always evolved with the communication technologies of its time (see Figure 1). Today, we find ourselves in a new transition. Podcasts, blogs, open code repositories, online video tutorials, social media threads, and collaborative documents offer us tools to share science faster, more broadly, and often more effectively. And yet, many of us cling, often out of habit or institutional inertia, to the PDF as our sacred format of choice.

Interlude: A 10 point guide for publishing like a proper scientist today

-

Everyone loves a 12-month publishing cycle. The anticipation! Submit, wait four months, get cryptic reviewer comments, revise, wait again. By the time it’s published, you’ve changed institutions, and forgotten half the project. Nothing builds character like slow feedback.

-

The gospel of the immutable PDF. Sure, your methods section might have unintentionally left out half the pipeline. But that’s the beauty of a PDF, it freezes your work in time, imperfections and all. It will never update, never improve. Ideal.

-

Why make your work reproducible when you can make it mysterious? Sharing your talk recordings, conference presentations, and analysis code are fine in theory. But if a colleague can actually replicate your analyses without emailing you… What is left of the scientific mystique?

-

Blogs are for people with hobbies. You might be tempted to write a short, clear explanation of your latest model. Maybe even highlight its limitations, and use cases. Resist. A true scientist knows that insights belong in 10-point font, two-column PDFs behind journal paywalls.

-

Video tutorials might help people. But helping people doesn’t earn citations. Making a clear, narrated walkthrough of your pipeline could save hundreds of hours for others. But is it indexed on PubMed? Will your tenure committee ever watch it? Exactly.

-

Podcasts are dangerously human. They reveal things like: how ideas were formed, where you struggled, what you’re curious about. These things don’t fit neatly into an abstract, and they might even make science feel accessible. Best avoided.

-

Preprints are anarchic. Why share your work before it’s been anointed by Reviewer 2? Imagine publishing without waiting 10 months, or receiving open feedback from multiple colleagues. Chaos.

-

Social media threads let you explain your work too quickly. And worse, people might actually read them. The brevity, the visualizations, the conversational tone… these are dangerous tools in the wrong hands. Some people even use them to summarize entire conferences in real time. Scandalous.

-

Visibility is a dangerous thing. People who communicate well across platforms often gain visibility. And visibility can lead to collaboration, funding, and recognition… but not necessarily the “right kind.” A real scientist measures success with impact factors, not impact.

-

You might enjoy it. Writing a blog post, recording a video, responding to a comment on your tutorial… These are activities that can feel energizing, engaging, and rewarding. This sets a dangerous precedent.

Breaking the rules is how we got here

When scientists started mailing letters across the world, it was not official publishing. When journals went online, people doubted the legitimacy of digital peer review. When preprints first appeared, they weren’t respected. Each of these shifts felt uncomfortable, even inappropriate, at first. But they shaped what we now consider standard. So maybe a video tutorial is today’s Darwin’s letter to Hooker. Maybe your blog post is the Philosophical Transactions of your circle. Maybe the tools we’re hesitant to legitimize are exactly the ones the next generation will take for granted.

The long game of modern science communication

I’ve personally found that the time I have “lost” engaging in modern forms of communication has repaid me in unexpected but meaningful, and quantifiable ways. For instance:

-

During my PhD, a spontaneous exchange in the OHBM Open Science Room led to a collaboration that became one of my most impactful projects. What started as a casual conversation evolved into a multi-institutional publication with a PhD student in another continent working on auditory brainstem nuclei.2 Together, Kevin Sitek and I produced something far greater than either of us could have achieved independently. It remains my second most cited manuscript to date.

-

Around the same time, I became involved in a multi-species brain imaging project that began with a spontaneous exchange on social media and evolved into a full collaboration. Katja Heuer, a researcher in brain evolution and development, had posted a request asking whether anyone could segment a dolphin brain MRI. I responded, applied my segmentation software to the data, and produced accurate gray matter segmentation within hours of her initial post. This quick success sparked a series of follow-up conversations with Katja, eventually leading to a collaboration in which I helped segment 34 non-human primate brains.3 The experience not only earned me a co-authorship but also broadened my technical perspective, demonstrating that the methods we had developed for human imaging4 could generalize to other species.

-

After reading blog posts on LayerfMRI.com, I reached out to Renzo Huber to contribute to the open-source LayNii software suite. What began as an informal connection through shared online resources led to a deep technical collaboration, and eventually my first last-author paper.5 By 2024, LayNii had become the most widely used software in its niche, surpassing even established tools like FreeSurfer,6 and BrainVoyager7 in this very specific domain (see 8, Figure 1). To date, this has also become my most cited publication, reflecting not just academic attention but real-world utility, and widespread adoption in the field.

-

Building on this spirit of open collaboration, I began experimenting with open peer review by informally inviting colleagues to comment directly on my preprints. In one instance, I reached out to Nikola Stikov (a fellow MRI scientist I knew only through social media) and invited him to review my bioRxiv preprint9 (see version 1 comments section). His feedback, shared publicly in the bioRxiv comments section, served as an additional review and helped me refine the final, peer-reviewed publication.10

-

Not all fruitful exchanges came through formal research collaborations. I once received an unexpected invitation to publish a deeply niche, “non-publishable” side project: an English translation, and contextual commentary on a scientific paper from the 1880s. The editor, Dr. Maria Holland, who had read my social media posts offered the perfect venue for it.11

-

Even passive engagement with modern communication platforms sometimes sparked new directions. Long-haul flights became opportunities for discovery. While listening to a podcast episode featuring Audrey Fan on Neurosalience,12 I was inspired to adapt my high-resolution, limited-coverage imaging methods10 toward clinically relevant applications.13 I’ve never met Dr. Fan beyond sending her a single email of thanks, she likely has no idea how influential that podcast was on my work.

-

Finally, thanks to a mix of writing scientific blog posts, recording video tutorials, dabbling in podcast production, and the occasional social media thread, in addition to regularly publishing fully peer-reviewed, traditional scientific papers, I somehow ended up being invited to write this very commentary, ironically, on modern scientific publishing.

These moments were not born in formal review processes or indexed journals, they emerged from being open, visible, and curious in public scientific spaces. They were not distractions from “real” science; they were how real science happened.

But not without risks

This modern publication ecosystem is not without its shadows. The line between authentic engagement, and performative self-promotion can blur easily. It’s tempting to chase followers, impressions, and visibility to become an “academic influencer” chasing metrics, rather than a scientist pursuing insight. Just because someone produces slick videos, engaging posts, or charming podcasts doesn’t mean their science is stronger, or even sound. A good thumbnail is not a good hypothesis.

Michael Strevens,14 in The Knowledge Machine, describes science’s strength as its “Iron Rule”: an obsessive commitment to empirical argument, method, and rigor. This rule demands that, regardless of how science is communicated, its foundation must remain intellectually dry, and methodologically sound. Communicating well should never replace writing excellent papers, it should amplify them.

Conclusions

Still, in a world where science is increasingly politicized, misunderstood, or actively undermined, those of us who have the privilege, and skill to speak across platforms may carry a new kind of responsibility. If a tutorial video, a podcast, or a social media thread can clarify science to someone outside our echo chamber, or inside it, then perhaps we owe it to the discipline to keep pressing “record.”

The landscape has changed. Today’s early-career scientists are not just navigating research, they’re navigating a social, digital, political, and economic environment vastly different from the one their mentors came up in. Even the simple act of writing and reviewing scientific work is being reshaped by artificial intelligence, adding yet another dimension changing the landscape of science communication.15 Gatekeeping old channels won’t preserve science, it might instead paralyze it. Maybe it is time to accept that progress might come one video tutorial at a time.

Therefore, no, I’m not going to stop publishing PDFs. Peer review, archiving, and formal structure are still extremely critical for science (in fact most of the references in this manuscript are pointing to traditional PDFs). However, I am going to keep supplementing my PDFs with videos, blogs, threads, and conversations, before, during, and after publication. Not to replace scientific rigor, but to enrich the ecosystem around it. To make science more visible, more alive, and above all, more human.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this work.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.