Introduction

Belonging under the umbrella of severe mental illness, psychotic disorders typically manifest during adolescence or early adulthood and their course often involves symptom recurrence or relapse.1–8 Psychotic disorders refer to disorders belonging to the schizophrenia spectrum as well as other severe illnesses (such as bipolar disorder) which can also show psychotic symptoms despite being distinct illnesses in the DSM-5.9 These disorders are heritable conditions with genetic overlap10,11 and could be considered along a nosological continuum.12 Across psychotic illnesses, the intensity of psychotic symptoms contributes to significant social and occupational functional impairment,7,8,13,14 rendering schizophrenia amongst the top 15 causes of disability worldwide15 and representing a significant burden for individuals, families, and communities.16,17 Current first-line treatments are largely effective in controlling acute episodes of positive psychotic symptoms; however they are less effective for negative symptoms18–21 which are associated with cognitive deficits, particularly episodic memory.22–24 Cognitive deficits and negative symptoms both predict poorer functioning.25,26 Gaining a better understanding of episodic memory impairments might thus provide insight into the underpinnings of such poor functional outcomes in psychotic illness.

Episodic Memory in Psychosis

Positive and negative symptoms are the diagnostic hallmark of schizophrenia9; yet a majority of patients also experience cognitive impairment, particularly prominent in the domain of episodic memory.27–31 Verbal memory is a specific type of episodic memory involving language information and shows amongst the highest rates of impairment in schizophrenia (d = 1.17).27,31 It is also noticeable in individuals at clinical high-risk and with first-episode schizophrenia, even when considering intelligence, executive functioning, and working memory.28–34 Verbal memory has transdiagnostic relevance and is also significantly impaired in bipolar I disorder (d = 1.05).27 Clinically, poorer memory performance is strongly predictive of transition to psychosis, even when accounting for general cognitive ability and medication.28,35 Relatives of persons with schizophrenia also show memory impairments, indicating that memory impairments may be a heritable precursor for psychosis, and changes in episodic memory may coincide with the emergence of psychosis.36 Our previous work further showed that verbal episodic memory predicts early remission following a first episode of psychosis (FEP) with association between memory capacity and clinical outcome also holding over time.37,38 Findings in FEP span the entire psychosis spectrum and can thus be considered particularly meaningful for the development of psychotic disorders. Baseline verbal episodic memory and persistent negative symptoms were the strongest predictors of social and occupational functioning after two years of care39,40 and both factors predicted future employment status.41 Memory capacity often remains stable following a FEP,42 but there is evidence for selective worsening of verbal episodic memory after a 10-year period43–46; these dynamic changes may explain why memory has such a central association with functioning47,48 and quality of life.49,50

Episodic memory is an important dimension of cognitive impairment and functional outcome in psychotic illness. Non-invasive measures of brain structure and function, through neuroimaging, have provided important insights into the neural correlates of memory such as the hippocampus. Decreased hippocampal volume in schizophrenia51–55 has been linked with memory performance56 but the hippocampus does not act in isolation; its role in memory is likely driven by connectivity with other regions, such as dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,57 parietal areas58,59 and the medial temporal lobe.60 Below, we describe key contributing factors to the relationship between memory impairments and functioning, including hippocampal circuitry, relational memory, social cognition, and negative symptoms.

Key Components of our Model and their Connections

The Hippocampus and its Associated Circuitry

The hippocampus and associated circuitry have long been implicated in the emergence of psychosis.53,61 Evidence from Misic et al. establishes the hippocampus as a key convergence zone for cortical regions.62 A better understanding of hippocampal-cortical dysconnectivity in psychosis may shed light on the highly robust finding of hippocampal structural abnormalities in schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorder.63–65 Dense hippocampal connections to other cortical regions suggest a role for the hippocampus in the manifestation of functionally important cognitive and clinical symptoms, namely memory deficits and negative symptoms. Recent advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition and analysis, including graph theoretical techniques to summarize brain connectivity,66,67 have allowed for quantitative in vivo measurement of the brain,68,69 offering an unprecedented opportunity to investigate individual hippocampal components that may be dysfunctional in schizophrenia. We recently demonstrated how alterations in hippocampal centrality (a graph measure denoting hippocampal-cortical connectivity) relate to episodic memory and negative symptoms in FEP.70 This work revealed for the first time that hippocampal-cortical connectivity, particularly through myelin-rich hippocampal output regions, is reduced in people with FEP and that its relationship with negative symptoms is mediated by verbal memory over time.

Relational Memory and the Hippocampal System

Relational memory also belongs in the category of episodic memory and describes the memory of a specific relationship between two items.71 Deficits in relational memory can be observed across the psychosis spectrum (including affective psychoses),72–83 based on which we suggested relational memory as a potential biomarker for psychosis.84 Anatomical and functional MRI studies show that episodic memory, and especially relational memory, correlate with activity in the hippocampal system and prefrontal cortical regions which appear to work in tandem to form contextual bonds between distinct memory items.85–97 As proposed by Eichenbaum, the particular role of the hippocampus in this process lies in flexibly updating and integrating information and context.85 In individuals with psychosis, including schizophrenia, abnormal activity can be observed in hippocampal and cortical regions during relational memory tasks.60,97–100

Social Cognition, Relational Memory, and the Hippocampal System in Schizophrenia

Social cognition comprises the cognitive processes needed to successfully navigate social interactions, and includes the domains of emotion processing, social perception, attributional bias, social knowledge and theory of mind (ToM).101 ToM is considered a mentalizing ability and describes the inference of others’ beliefs and mental states, as well as the interpretation of their social behaviour.102 Mentalizing deficits show large effect sizes in recent onset psychosis, early-course bipolar disorder and across schizophrenia spectrum disorders.103–108 ToM shows a strong relationship to functioning relative to other domains,108–110 with interventions targeting ToM leading to improved functional outcome in schizophrenia.111 ToM tasks requiring the attribution of intentions, such as the Hinting task,102 are also strongly related to episodic memory.112 Relational memory abilities are proposed to not just bind objects to form contextual memories but to also determine how we process, perceive and integrate social cues.113 Montagrin et al.114 relate this idea back to the hippocampus and associate the hippocampal ability to flexibly update contextual cues to the ability to navigate through social dynamics. Eichenbaum’s updated relational memory theory proposes that the hippocampus creates a ‘memory space’ creating an association between events and items,115 rendering the hippocampal system central for cognitive processes and social interactions.116,117 Understanding the relationship between the hippocampus, relational memory and social cognition could thus be particularly informative for investigating the underpinning of poor functional outcomes of psychosis.

The Role of Negative Symptoms

Negative symptoms include the diminished ability to exhibit emotion (blunted affect), reduced speech (alogia), pleasure (anhedonia), and motivation (avolition), and social withdrawal (asociality).9 These prevalent symptoms appear early in the illness process and can increase with time.118–120 They strongly relate to poor functioning25 and have been reported in at-risk populations, FEP, and enduring schizophrenia.118–120 Beyond the diagnostic role of negative symptoms in schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, negative symptoms are evident across the psychosis spectrum including bipolar disorders.121,122 In a large Australian cohort (n=1469) comparing patients living with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, all groups had negative symptoms. Patients living with schizophrenia had the most severe symptomatology, while patients living with schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder still had similar severity of negative symptoms.123 Diagnostic comparisons of the core negative symptom domains showed that schizophrenia and bipolar disorder differed only on blunted affect and alogia items. Bipolar disorder patients with a history of psychosis did not differ from those without a history of psychosis on negative symptom severity,121 and the severity of avolition/apathy in bipolar disorder was comparable to that of schizophrenia patients.124–126 While mechanisms underlying negative symptoms, such as depressive symptoms or brain activity,124 may differ between bipolar and schizophrenia spectrum disorder, the transdiagnostic nature of negative symptoms is thus well-established.

A Testable Neurocognitive Model

Our previous work in FEP clearly identified associations between persistent negative symptoms, verbal episodic memory127,128 and hippocampal structure.70,129,130 These findings echo the work of others reporting an association between hippocampal volume, memory131 and negative symptom severity132–135 yet very few conceptual models currently account for this association. One of these models from Harvey et al. posits related etiologies but no specific underlying mechanism.136 Tying in the social cognitive impairments discussed above, ToM in schizophrenia is not only related to functional outcome, but also to negative symptoms and verbal episodic memory.112,137–142 Schafer & Schiller propose an association between the hippocampus and social impairments in clinical populations, suggesting the hippocampus is involved in general relational processes.143 The hippocampus may thus organize social information into relational maps to guide social decision-making. As such some social impairments may be secondary to psychotic symptoms while others may be rooted in faulty hippocampal-based representations of social maps. It has further been proposed that the shared neural substrates between social cognition and negative symptoms may involve frontal-temporal circuitry.144

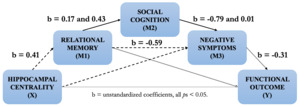

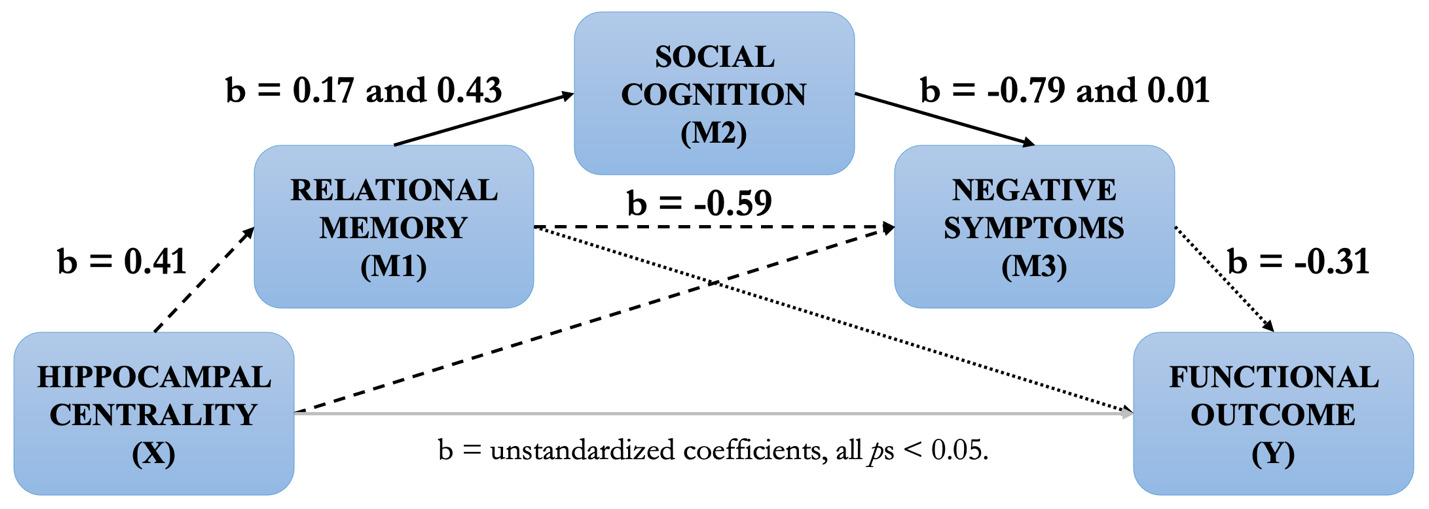

Based on this cumulative body of work, we propose a testable neurocognitive model of psychosis (spanning the schizophrenia and bipolar disorder spectrum) from hippocampal centrality to functional outcome (see Figure 1 below). This model builds upon our previous work and is rooted in hippocampal centrality based on findings (i) showing that reduced hippocampal centrality predicts negative symptoms as mediated by memory in FEP (R2 = 0.26, Figure 1, dashed lines).70 In schizophrenia spectrum disorders, (ii) the relationship between memory and negative symptoms is further mediated by social cognition (R2 = 0.07, solid black lines),145 while (iii) memory also predicts functional outcome in FEP through negative symptoms (R2 = 0.14, dotted lines).146 Based on these mediation analyses, we hypothesize a temporal development from decreased structural and functional hippocampal dysconnectivity (assessed through centrality) leading to relational memory impairments and, in turn, social cognition impairments. These impairments pave the way for the emergence of negative symptoms, which ultimately worsen functioning.

While functional outcome is the ultimate stage of this model, our goal is to systematically evaluate the contributions of hippocampal centrality to functioning through relational memory, social cognition, and negative symptoms, while taking into account potential moderating factors. It is also inspired from Rubin et al.,117 who theorized that successful social behaviour depends upon constant encoding, updating, and flexible manipulation of relational memory representations via the hippocampus. Our model unites and extends theories of the hippocampal system and notably integrates cortical connectivity, since complex information processing relies on the coordinated performance of multiple brain regions or networks. We set out to test the overall model, for which each component was derived from our prior findings, for the first time.

A Subtyping Approach Integrating Clinical Stages

Data-Driven and Clinical Staging

From our prospective model, we propose to develop a translational approach with potential clinical applications. We will use an unsupervised machine learning technique called Subtype and Stage Inference (SuStaIn) to disentangle temporal and phenotypic heterogeneity and identify subgroups with common patterns of inferred disease progression across neurobiological, clinical, and cognitive features.147 SuStaIn builds upon and combines ideas from clustering and disease progression modelling, which makes it possible to identify subgroups from cross-sectional data with common patterns of disease progression as well as assign new subjects to a subgroup based on these features. This method holds potential for precision psychiatry, as it indicates which symptoms an individual has already developed, and which future progression is to be expected. Based on event-likelihood modeling, SuStaIn can use cross-sectional data to predict events which are seen in the majority of the sample to occur earlier in the disease progression, whereas events which are seen in only a few individuals will occur later. Combining neurobiological and clinical data provides even further insight into the underlying disease biology and a mechanism for in vivo fine-grained stratification beginning at early disease stages. In this context, SuStaIn is thus providing a data-driven approach towards the staging of mental illness, adding to literature on traditional clinical staging models as initially proposed by McGorry et al.148

Clinical staging models can map the development, progression, and extension of mental illness over time, and may prove to be heuristically and practically useful in clinical practice, particularly for biomarker research.149 With respect to the psychosis continuum (see150 for more details), we can define multiple stages from at-risk states to the first episode of psychosis to recurrence of multiple episodes to severe, persistent, and unremitted illness. When considering that the collection of longitudinal imaging data often proves challenging in clinical populations, applying machine learning in cross-sectional data can be of clinical value. Sampling across populations of first-episode as well as enduring psychosis allows for data-driven results to be translated to meaningful clinical stages.

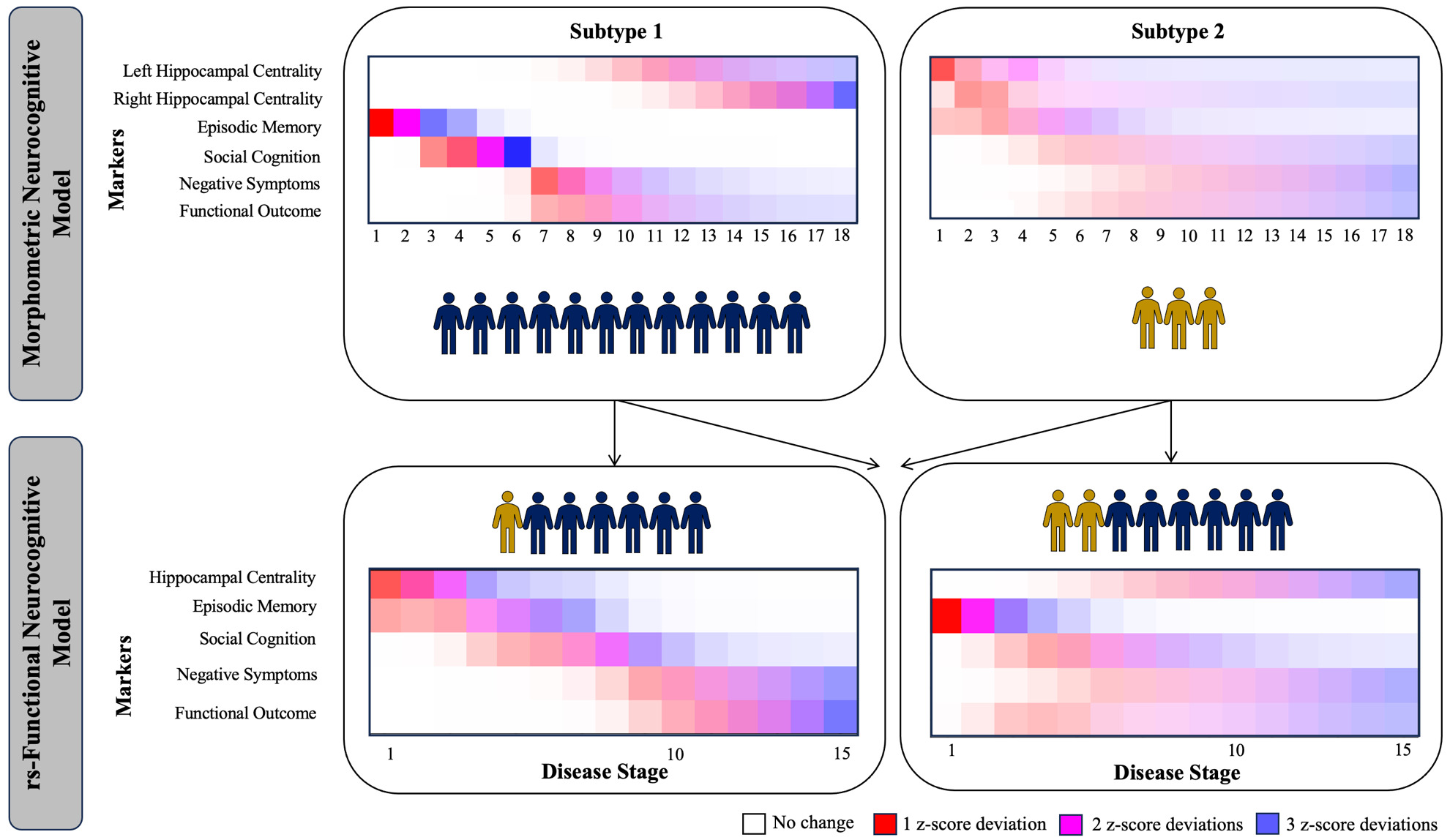

Applications of SuStaIn to date

Originating in the field of neurodegenerative illness, SuStaIn has been successfully used in multiple neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease,147,151,152 fronto-temporal dementia,153 Parkinson’s disease154 and multiple sclerosis.155 One of the strengths of SuStaIn is its capacity to work with purely cross-sectional data because it requires no information about change over time in a given individual, but instead infers staging from bio/clinical marker severity via a disease progression model. Resulting subtypes have been validated with longitudinal data.147 Moving into the field of psychiatry, two independent investigations recently applied SuStaIn to model the development of cortical and subcortical volume reductions156,157 in psychosis, identifying one subtype where reductions in hippocampal volume lead to cortical atrophy. While this combined work from the fields of neurodegenerative illness and psychosis has focused on the progression of neuroimaging-based measures, work by Oxtoby et al.154 simultaneously integrated behavioural and neuroimaging (i.e., multiscale) data for the first time. On this foundation, we recently provided the first multiscale implementation of SuStaIn in the field of psychiatry,158 by investigating a neurocognitive model of psychosis spanning morphometry-based hippocampal connectivity, episodic memory, social cognition (emotion recognition), negative symptoms and functional outcome. Across patients with affective and non-affective psychosis, we identified two subtypes of psychosis in addition to a group of patients with little impairment. In the first morphometric subtype, we observed a development from reduced memory toward poorer social cognition, increased negative symptoms, lower functional outcome and then reduced morphometry-based hippocampal connectivity, while reduced hippocampal connectivity led the disease progression in a second (smaller) subtype. This work has since then been extended in the modality of resting state functional MRI in FEP.159 Figure 2 shows the progression patterns in the morphometric and resting-state functional models, revealing similar progression patterns across modalities. As both analyses partially used the same sample, this figure further shows how FEP participants with impaired morphometric connectivity might also showed impaired resting-state functional connectivity, as well as how many individuals without morphometric dysconnectivity might show resting-state functional connectivity. Importantly, these results visualized that morphometry-based and rs-functional connectivity have an additive effect in explaining the observed disease progression according to our model. Both studies considered reductions of hippocampal connectivity towards cortical regions vs. reductions within the hippocampus itself as the foundation of this model. To thus build on these findings and potentially identify one overarching measure of hippocampal dysconnectivity in psychosis, the relationship between graph-theoretical measures and cognition (i.e., participation coefficient67 and relational memory networks) needs to be investigated further. Through such an approach, SuStaIn might result in one single subtype of psychosis, with increasing certainty and applicable to a broader range of patients.

Need for a new study

Our body of work over the past two decades and that of others has consistently supported links between the hippocampus, relational memory, social cognition, negative symptoms, and functional outcome in psychosis. Our recent mediation findings have contextualized this work and allowed us to develop an integrative model, which we preliminarily tested through novel machine learning approaches; yet there are several needs which must be addressed through a new study. First, there remains the need to validate this model using a large, well characterized sample for improved consistency and reliability and to accommodate advanced analyses. Although the current literature on functional outcome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is substantial, there are no studies that have examined a potential brain mechanism that can account for the relationship from cognitive impairments to functioning, except for our own implementation of SuStaIn, which was limited by sample size. Second, the proposed imaging protocol leverages recent developments in high-resolution and quantitative MRI to generate a rich set of multimodal imaging data from a well-characterized sample with clinical and cognitive data. Task-based functional MRI (fMRI) will identify relational memory networks, considering the neural substrates of relational memory as the foundation of the model for the first time. Third, we propose a translational component by applying a novel machine learning technique (SuStaIn) to subtype participants and determine stages of progression using cross-sectional data. With this model, it will be possible to predict individual-level membership into potential subgroups and trajectories and outline the relevance of multimodal hippocampal dysconnectivity and relational memory impairments in evoking poor functioning in psychosis. This could be used to reduce heterogeneity in intervention studies and/or help identify those who would benefit from specific interventions. Our model might also prove applicable to other psychiatric conditions in which hippocampal centrality, memory, and functioning deficits can be observed (e.g., depression160,161).

Need for open science practices

Finally, this study will help establish an ethical framework for Open Science to encourage other researchers in the field to contribute to and use this unique database. The term Open Science (OS) has many definitions in terms of implementation. We aim to develop the necessary framework to share scientific data and resources while protecting participants’ rights. OS is a key strategy to maximize impact in the field, promote forward-thinking, encourage collaborative endeavors, and facilitate discovery. The Tanenbaum Open Science Institute (TOSI) of the Montreal Neurological Institute is a major leader in the development of such a framework.162 The Douglas Research Centre in Montreal, Canada, the primary research site for the proposed study, has implemented an OS strategy in collaboration with TOSI.163 A key objective is to capture the data generated by all of our research activities and to ensure that this data is used to improve approaches to mental health care locally, across Canada, and globally. Our initiative will have a lasting impact on the field with the generation of high-quality OS schizophrenia datasets.164–166

Aims & Hypotheses

Using a multi-site, cross-sectional study, we propose to collect data from 300 people with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar I disorder varying in clinical stages and from 150 non-clinical controls to address two distinct aims. First, we aim to refine and validate our model of relational memory impairments in psychosis by applying partial least squares (PLS) to identify multivariate patterns of brain-behaviour associations and by incorporating these into a mediation model using a bootstrapping approach. Here, we hypothesize to (a) identify latent variables showing significant associations between decreased structural and functional hippocampal centrality, poorer relational memory and social cognition, and decreased functioning, including more severe negative symptoms and poorer outcome. In addition, we hypothesize that (b) a bootstrapping mediation approach to validate our model will reveal a significant indirect effect from decreased multimodal hippocampal centrality to impaired relational memory to poorer social cognition to more severe negative symptoms to poorer functional outcome. As secondary hypotheses, we expect that (i) impairments in people with psychosis relative to non-clinical controls on relational memory, social cognition, and hippocampal centrality will be confirmed, and that (ii) male sex, greater chronicity, greater cannabis use, and higher medication dosage (antipsychotics and others) will emerge as reliable predictors in the PLS analysis and male sex and longer chronicity will act as moderators in the mediation model.

Secondly, we aim to translate this mediation model into a subject-level predictive model by applying a novel machine learning approach to identify subgroups of participants based on patterns of disease progression. Here, we hypothesize to (a) identify a subgroup of patients showing a disease trajectory consistent with our mediation model (hippocampal centrality – memory – social cognition – negative symptoms – functional outcome) as a primary subtype based on both brain imaging and behavioural data. As a secondary hypothesis, we (b) expect to identify a smaller subgroup(s) of participants who show a distinct pattern of disease progression, potentially including control participants and cognitive and functionally unimpaired patients. Lastly, we aim to contribute to open science by establishing an ethical framework for Open Science, where data sharing can be facilitated and international collaborations in the field of psychosis are encouraged and fostered.

Methods

Participants

Three hundred individuals with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar I disorder with psychosis will be recruited across the three study sites (Montreal, Vancouver, and Ottawa). Visits will be conducted in English and French. For inclusion and exclusion criteria see Table 1. One hundred fifty non-clinical participants will be recruited from various websites, such as Kijiji and Reddit, in the same ratio per site. Controls will be similar to psychosis participants on age, sex and parental education. See Table 2 for inclusion and exclusion criteria of controls.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval has been granted by the research ethics board across all three sites. For the Montreal site, the Douglas Research Centre approved the study under protocol 2023-763 on April 23rd, 2023. For the Vancouver site, the UBC Behavioural Research Ethics Board approved the study under protocol H23-03376 on March 26th, 2024. For the Ottawa site, the study was approved under protocol REB2023020 on May 8th, 2024. The study will be conducted in compliance with the declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to the study.

Procedure

Screening

Participants will be contacted via phone during which a screening form will be completed. The screening will specifically focus on eligibility criteria by assessing clinical stability over the past 3 months, including the systematic assessment of suicidality, recent hospitalization and any changes to neuroleptic medication. We will further screen for the status of their general health, recreational drug use and the possibility of not using prior to the visit, physical disability, weight, height and waist circumference, and the potential of feeling claustrophobic in an MRI. They will be offered a mock scan visit, if they desire.

Visit 1

During the first visit, participants will be asked to sign the consent form. The first visit will then start with the sociodemographic interview and questions on medication and adherence. The next assessment will target the diagnostic assessment through the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).167 The MINI will be administered in two parts, with the second part covering family history of mental illness which will only be administered in controls. The next assessment will be for substance use through the Chemical Use, Abuse, Dependence (CUAD) Scale,168 followed by the assessment of premorbid IQ through subscales of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.169 Afterwards, participants will undergo a hybrid interview assessing positive, negative, and manic symptoms through the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-6) (patients only),170 Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS),171 and the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS).172 The last part of the hybrid interview is the assessment of functioning through the Personal and Social Performance (PSP) Scale.173 After a 5-10 minute break, the session will continue with the assessment of premorbid adjustment through the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS)174 and neurocognitive assessments through the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB).175 Afterwards, the Ambiguous Intentions and Hostility Questionnaire (AIHQ-B)176 and the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory177 will be administered, followed by the pen and paper assessment of verbal fluency,178 and the NAART179 for premorbid IQ.

Visit 2

The second visit will commence with the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – immediate recall,180 the Symbol Coding Test169 and the Trail Making Test.181 Emotion recognition will then be assessed through the Penn Emotion Recognition Task (ER40-B),182 followed by the assessment of depressive symptoms through the Beck’s Depression Inventory – II.183 The next step is the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – delayed recall and recognition,180 followed by the assessment of theory of mind through the Hinting Task.102 Then, the MRI scan will take place, including the Relational and Item-Specific Encoding (RiSE) Task in the scanner.100 Notably, all the same questionnaires and tasks will be administered in patients and controls. Afterwards, participants will be thanked for their participation and will receive monetary compensation after each visit.

Clinical and Behavioural Measures

Sociodemographic Interview

Our sociodemographic interview combined with a systematic chart review will provide systematic information on multiple dimensions including duration of illness, age of onset, and duration of untreated psychosis, factors known to influence memory performance in schizophrenia.46,184 We will also collect information on sex and gender,185 age, physical health, handedness, parental education, level of education, premorbid IQ and socioeconomic status. Premorbid IQ will be assessed by the means of a reading task (NAART179) and estimated IQ based on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI subscales: vocabulary and matrix reasoning measure169). We will further assess dosage and adherence of primary medication over the past month. If possible, length of time since medication was first prescribed will be acquired through medical chart review.186,187

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)167

The full MINI, adapted to DSM-5 criteria, will be administered with a research assistant on site. The administration of the MINI will allow us to confirm a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum or bipolar I disorders (see inclusion criteria) in patients and the absence of such lifetime diagnoses in controls. The MINI will further be used to address the exclusion criterion of current substance use disorder in patients and non-clinical controls. The MINI has good psychometric properties, with an interrater reliability of >0.75 on all subscales.167

Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS)174

The PAS is a measure of premorbid social and occupational functioning and will be used as a potential covariate in our analysis to account for the confounding effect of premorbid adjustment on current functional outcomes. The PAS used in our study will assess premorbid functioning on the two subscales of functioning in childhood (up to age 11) and in early adolescence (12-15 years). Per subscale, the PAS assesses sociability and withdrawal, peer relationships, scholastic performance and adaptation to school on a scale from 0 (excellent performance) to 6 (severe impairments). Scores are summed per subscale and divided by the total possible number of scores on the subscale. An overall PAS score is then calculated by averaging the subscale scores. The PAS has been shown to have good reliability, with an interrater reliability of 0.74.174

Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS-6)170

We will use the PANSS-6 to assess psychotic symptoms using the recently developed SNAPSI interview,188 now validated in French Canadian in collaboration with the authors.189 The PANSS-6 consists of 6 items in total, 3 assessing positive symptoms and 3 assessing negative symptoms, which are all measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (absent) to 7 (severe). The scale will be administered by a trained rater and has been shown to have an interrater reliability of 0.74.190

Beck’s Depression Inventory – II183

The BDI-II is a self-report measure of depression covering symptoms as experienced throughout the past two weeks. It contains 21 items in total which are assessed on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe). In our study, the BDI-II is used to assess depressive symptoms in our sample as well as for the potential of including depression as a confounding factor in our analyses. The BDI-II has good psychometric properties183 with an internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87 at pretreatment.191

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)171

The YMRS is a self-report scale consisting of 11 items and assesses manic symptoms over the time span of the past two days. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (normal) to 4 (severe). The YMRS has good psychometric properties, with an interrater reliability of 0.93.171

The Chemical Use, Abuse, Dependence (CUAD) Scale168

The CUAD is a measure of drug use, abuse and dependence and will potentially be used to covary for effects of drug dependence (especially cannabis use) in our analyses. The CUAD will be administered throughout a semi-structured interview and consists of 10 items in total. It measures frequency of drug use on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (less than 1x month) to 5 (daily) and duration of drug use on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (less than 1 month) to 3 (longer than 6 months). Mode of administration and amount are assessed as well. The scale has been shown to have good psychometric properties, with acceptable criterion validity and an interrater reliability of 0.82.168

Neurocognitive Measures

Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB)175

The CANTAB is a validated measure of neurocognition in the field of psychosis192 and will be used to measure the domains of attention, working memory, visual learning & memory, and reasoning & problem solving. In addition to the test battery, pen and paper measures for the domains of processing speed and verbal learning & memory will be administered. See Table 3 for a summary of all neurocognitive domains that will be assessed, their respective measures and their duration of administration.

Relational memory and social cognition measures

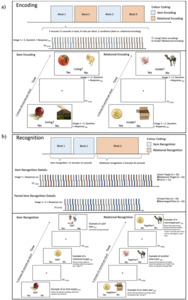

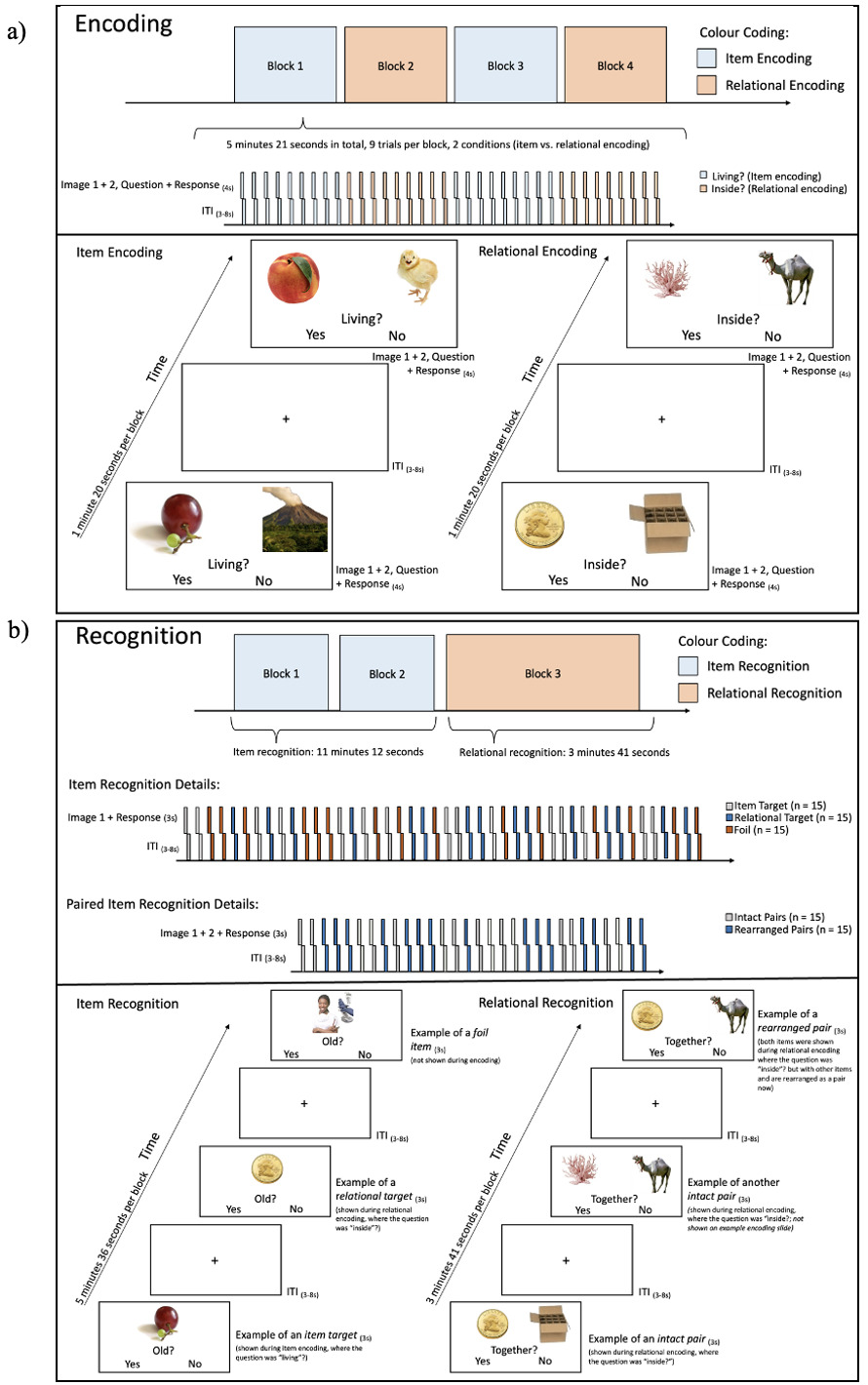

The Relational and Item-Specific Encoding (RiSE) Task100

The RiSE task is a validated encoding task involving item and relational encoding conditions. During item encoding, pairs of images are presented for 4 seconds each followed by a 3-8 jittered inter-trial interval. Participants are required to press a button to indicate if any object shown on the image is a living object. During relational encoding, pairs of images are presented for 4 seconds each and participants are required to press a button to indicate if one of the objects can fit inside the other in real life. Item and relational memory are tested sequentially with a recognition task, in which novel objects as well as the item- or relationally-encoded objects are presented one at a time (item test) or in pairs (relational test). Participants are then asked to indicate if each object is ‘old’ (item test) or if the pairs were presented together originally (relational test).

Participants will be asked to engage in a practice run outside of the scanner. This practice run will begin with the practice of 5 pairs of item encoding followed by 5 pairs of relational encoding. To practice recognition, participants will see 10 pairs related to item recognition, and 10 pairs related to relational recognition. For the encoding task inside the scanner (see Figure 3a), participants will go through 4 blocks of 9 pairs each, with blocks of item and relational encoding alternating. In block 1 and 2, 5 pairs will be positive for the living/inside condition while 4 pairs will belong to the non-living/not inside condition, and vice versa in block 3 and 4. Participants will be asked to respond with their right index finger for “yes” and their middle finger for “no”. The recognition task in the scanner (see Figure 3b) will consist of three blocks. The first two blocks cover item recognition, 45 single items will be shown. 15 items will be images that were shown during item encoding (item target), 15 items will be images that were shown during relational encoding (relational target), and 15 items will be unrelated images. During relational recognition, 30 pairs of items will be shown, 15 are a collection of rearranged images that were not initially shown together, and 15 pairs which were shown together before. The task will take place in a 3T MRI scanner and will last approximately 25 minutes. The link to the task has been made publicly available: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ZEJ5W

Adapted Brief Battery of the Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation (BBSCOPE)193

The BB-SCOPE is a global measure of social cognition and assesses the domains of emotion processing, attributional bias and theory of mind. This battery consists of the brief version of the Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (BLERT-B)194 to address emotion recognition, the brief version of the Ambiguous Intentions and Hostility Questionnaire (AIHQ-B)176 to assess attributional style, and the full version of the Hinting Task102 to assess theory of mind. The Hinting Task includes 10 stories which describe dialogues between two people and all end with one person giving a social cue to the other person. Participants are then asked to socially interpret what the intention of the person was and what the cue really meant in this context. As the BLERT-B is not available in French, we will adapt the BB-SCOPE and use the second most suitable measure for emotion recognition instead, the brief version of the Penn Emotion Recognition Task (ER40-B).182 Throughout the BB-SCOPE, participants can gain up to 16 points on the AIHQ-B, 40 points on the ER40-B and 20 points on the Hinting Task. The proportion of correct responses is multiplied by 33.33 per subscale, resulting in a total score between 0 and 100. Scores below 60 are considered to indicate impaired social cognition. Overall, the original BB-SCOPE has been shown to have acceptable psychometric properties.193 Through the inclusion of the full Hinting Task in the BB-SCOPE, distinct scores of theory of mind can also be evaluated.

Negative symptom and functioning assessment

The Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS)172

The BNSS follows the NIMH MATRICS Consensus and assesses the severity of negative symptoms along the dimensions of blunted affect, alogia, asociality, anhedonia, and avolition for the duration of the past week. The BNSS was designed for clinical trials and other research use and is composed of 13 items which are measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (absent) to 6 (severe). The scale will be administered by a trained rater through a semi-structured interview. The BNSS has strong internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93.172 Importantly, the BNSS will also be administered in non-clinical controls to generate required data for our machine learning-related aims.

The Personal and Social Performance (PSP) Scale173

The PSP assesses functioning along the four dimensions of socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care and disturbing and aggressive behaviours. After each of these four dimensions is scored on an anchored Likert-type scale, trained raters select a 10-point range within a 100-point scale. This scale with recent improvement in scoring195 has shown excellent psychometric properties (see Chiu et al.196). Like the BNSS, the PSP will also be administered in the control group.

MRI Protocol

Structural and Functional MRI

Participants will undergo MRI scanning on a 3T MRI scanner at each site (Douglas: Siemens Trio; Royal: Siemens Biograph mMR; UBC: Philips Elition). Some differences between sites were unavoidable due to scanner differences. We are reporting the imaging parameters of the primary site (Douglas Research Centre). Participants will first undergo a localizer scan (duration = 17s, voxel size = 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.7mm, field of view (FOV) = 250mm, repetition time (TR) = 7.5ms, echo time (TE) = 3.69ms, flip angle = 20°). Then, the field maps for the encoding of the RiSE Task will be acquired (duration = 1m43s, voxel size = 2.5mm3, FOV = 225mm, TR = 555ms, TE1 = 4.92ms, TE2 = 7.38ms, flip angle = 60°), followed by the encoding task (duration = 5m43s, voxel size = 3mm3, FOV = 222mm, TR = 1000ms, TE = 31ms, flip angle = 60°), which has been shown to robustly activate the hippocampus and surrounding areas (see “Relational memory and social cognition measures” for a detailed description of the RiSE100 design). Anatomical MRI will consist of an MP2RAGE sequence (duration: 4m23s, voxel size = 1mm3, FOV = 256mm, TR = 5000ms, TE = 2.88ms, flip angle 1&2 = 4°), which produces a quantitative T1 (qT1) map, serving as a proxy measure of myelin content, as well as a standard T1-weighted-like image. We will further acquire a high-resolution T2-weighted image to capture detailed hippocampal subfield information (duration: 6m10s, voxel size = 0.7mm3, FOV = 224mm, TR = 2500ms, TE = 198ms). We will then acquire a brief resting-state functional acquisition (duration = 5m37s, voxel size = 3mm3, FOV = 222mm, TR = 1000ms, TE = 31ms, flip angle = 60°) followed by the RiSE Recognition Task including two item recognition runs and one relational recognition run (durations: each item run = 5m58s, relational run = 3m57s, all voxel size = 3mm3, FOV = 222mm, TR = 1000ms, TE = 31ms, flip angle = 60°).

Incidental Findings

Incidental findings, either found by the MRI technician or a member of the research team conducting reviews/analysis of the MRI scan, will be submitted to a radiologist to review at each site. We will then contact the participant to let them know that a revision by a radiologist was done of their brain MRI and physician follow-up will be recommended if necessary.

Multisite Data Harmonization

Clinical Assessments and Rating Calibration

Each site includes a clinical psychologist who will be responsible for the training of symptom raters and for quality of the administration of clinical interviews and clinician-rated scales. Calibration across sites will be performed by having videotape interviews rated by all three clinical psychologists and symptom raters, and inter-rater reliability will be calculated using the intra-class correlation coefficient.

MRI Acquisition Quality Assurance and Data Harmonization

We harmonized the scan protocols as closely as possible across sites with the imaging parameters reported above corresponding to the primary site (Douglas Research Centre). For example, the MP2RAGE acquisition time differs across sites (between 4 and 8 min) due to advanced acceleration (compressed sensing) reducing acquisition time. In addition, the T2-weighted FOV varies from 224 mm to 235mm. Some changes were also applied to all sites to ensure consistency, such as the 3mm3 fMRI acquisition voxel size, as a higher resolution was not feasible at all sites.

To address unavoidable scanner differences, we will employ ComBat Harmonization,197 a neuroimaging correction tool that minimizes site differences while preserving biological signal. This tool has been shown to increase statistical power and generalizability in both structural197,198 and functional199 multisite MRI data. We will also conduct analyses to better understand site differences as a means of elucidating both univariate and multivariate differences that can be expected. This will help estimate the minimum effect size necessary to estimate a true group difference.200

MRI Processing

Structural and Functional Parcellation

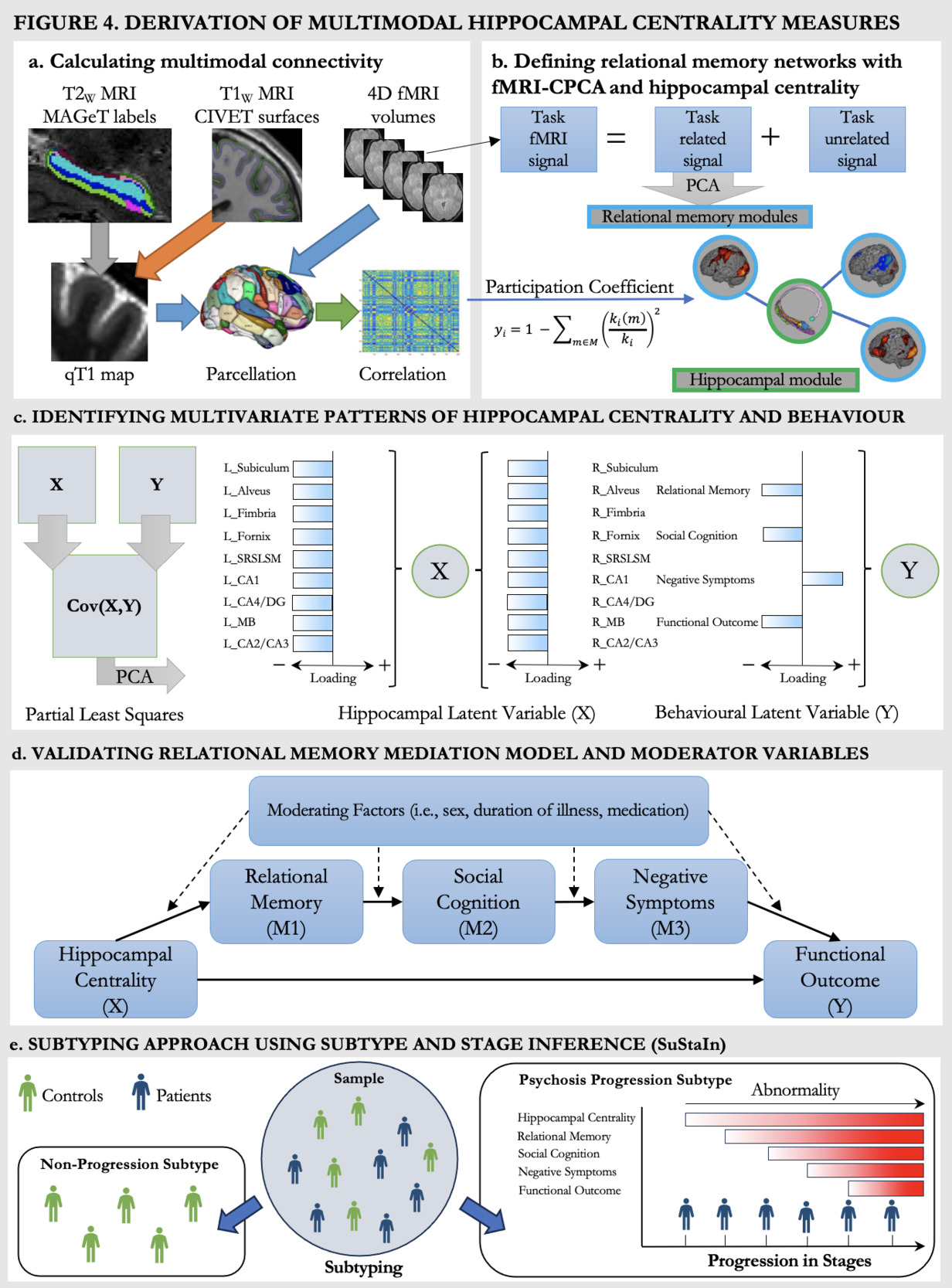

Structural hippocampal subfields will be derived through the MAGeT-segmentation procedure68 which will provide labels of hippocampal subfields for the T2-weighted MRI and will be registered to qT1 volumes (Figure 4a, grey arrow).70 MAGeT provides specific labels for the subfields cornu ammonis (CA) 1, CA2/3, CA4/dentate gyrus, subiculum, molecular layer, and for the white matter structures alveus, fimbria, fornix, mammillary bodies, thus resulting in 18 measures of hippocampal subfields in total.69,201 Cortical surface qT1 maps will be sampled from T1-weighted surfaces with CIVET202 (Figure 4a, orange arrow). qT1 surface maps and fMRIprep203 processed fMRI data will be parcellated via the Brainnetome Atlas204 (Figure 4a, blue arrows), resulting in 210 cortical measures and four hippocampal subfields (two per hemisphere). To then derive the relationship between hippocampal measures and the structural (qT1) cortical measures, we will first calculate group-level structural covariance matrices through Pearson correlations. To calculate subject-specific structural covariance matrices, we will then employ a jackknife procedure which uses a leave-one-out approach to identify individual contributions to the group-level covariance structure.205–207 As functional data is already processed on a subject-specific level, the jackknife procedure is not required and correlations are provided (Figure 4a, green arrow). Following these pre-processing steps, we will have a 228x228 correlational matrix showing the structural covariance between cortical and hippocampal regions, as well as a 214x214 correlational matrix showing the functional covariance between cortical and hippocampal regions.

Defining Relational Memory Networks

Coordinated spatial patterns of BOLD signal elicited by the RiSE task will be retrieved by constrained principal component analysis for fMRI (fMRI-CPCA).208–210 fMRI-CPCA employs multivariate multiple regression and PCA, constraining fMRI activation that related to task timing prior to PCA (Figure 4b). The spatial patterns for each dimension can be classified into pre-existing templates, and the BOLD signal changes associated with each can be interpreted for a functional interpretation of the spatial pattern.211 This means that fMRI-CPCA allows for the identification of task-predicted brain activity (via regression) in addition to patterns of coordinated activation (i.e., networks). This processing step will thus provide us with a data-driven way of defining cortical brain regions working together during our relational memory task in addition to the hippocampal network. These networks then build the foundation for deriving hippocampal centrality.

Calculating Hippocampal Centrality

Centrality is a graph-theoretical measure capturing connectivity relative to brain modules or networks. Centrality can thus capture the degree of connectivity of hippocampal regions to cortical regions during the memory task. Based on the fMRI-CPCA results, cortical regions will be classified into relational memory networks (Figure 4b, blue outline) and hippocampal regions will be sorted into a separate module (Figure 4b, green outline). The specific measure of centrality employed will be the participation coefficient66,67 (Figure 4b, equation). The participation coefficient looks at the connectivity of each region within their own module relative to outside of the module, providing potentially reduced hippocampal-cortical network connectivity in clinical populations. With regard to the hippocampus, we will thus have 18 structural measures of hippocampal centrality and 4 measures of functional hippocampal centrality.

Statistical Analyses

Identifying Multivariate Patterns of Hippocampal Centrality and Behaviour

We will first compare both patients and controls on main variables of interest: multimodal centrality, relational memory, social cognition, negative symptoms and functional outcome. Then focusing on patients, we will assess patterns of covariance between hippocampal centrality and behaviour with PLS.212–214 PLS identifies latent variables representing maximally covarying brain (multimodal hippocampal centrality) and behavioural (e.g., memory, symptoms, functioning, etc.) data (Figure 4c). We will leverage this multivariate technique to identify specific hippocampal subfields associated with the variables in our model, which will then inform which subfields we include in our input measure of hippocampal centrality for SuStaIn. In this PLS, we will also include potential moderators (i.e., sex, duration of illness, medication) which will be implemented in later analysis steps if significant. Reliability and significance of latent variables will be assessed with 1000 permutations and bootstrapping, a resampling method.215 This allows for estimation of the population parameter by repeatedly randomly resampling the data (e.g., 1000 times) and provides a confidence interval for the effect of interest. This will result in a ‘new’ and slightly different cohort of patients being randomly generated through sampling with replacement (each patient may be sampled multiple times). This process will be repeated 1000 times to form 1000 resampled cohorts (which each include all patients). In each of these resampled cohorts, the relevant statistical measures will be computed, and these results will be pooled to determine internal validation performance. We have recently used PLS to identify brain-cognition associations in psychosis216,217 and hippocampal-cognition associations in non-clinical groups.214 As PLS analyses are data-driven, the resulting relationships between the input variables and latent variables are dynamic. Hypothesis 1a) will be supported if we identify a latent variable which is significantly related to all variables of our model and will not be supported if we find no significant pattern showing associations between our measures of interest.

Validating the Relational Memory Mediation Model

We will assess our mediation model in the patient data (Figure 4d, solid lines) using the sem package in R,218 with hippocampal centrality as the predictor variable (X), relational memory as mediator 1 (M1), social cognition as mediator 2 (M2), negative symptoms as mediator 3 (M3), and functional outcome as the outcome variable (Y). Multimodal hippocampal centrality (structural and functional) will be assessed separately. As the PLS might reveal distinct relationships between hippocampal subfields and the behavioural/clinical variables, we will derive an averaged measure of hippocampal centrality based on the significantly associated regions per modality. Significance of the indirect (mediation) effects are assessed with bootstrap confidence intervals and model summary statistics. As suggested by Hayes et al.,219,220 we will perform a validation using bootstrapping.215 Hypothesis 1b will be supported if the identified associations are significant and not supported if the full indirect path from hippocampal dysconnectivity to functional outcome is non-significant. We will further assess the reverse model (functioning to negative symptoms to social cognition to relational memory to hippocampal centrality), which will allow us to identify sub-relationships through intermediate paths.

Contribution of Moderator Variables

To examine potential moderators, we will perform a moderated-mediation analysis on the patient data (Figure 4d, solid and dotted lines) for each potential moderator defined from PLS separately. Site effects will also be assessed as a moderator variable. Moderated-mediation refers to an indirect effect (e.g., the effect of predictor X on outcome Y through serial mediators M1, M2, and M3) that depends on the levels of a moderator variable (e.g., sex, site). The moderators selected for analyses stem from our previous work identifying sex as a contributing factor to the associations between verbal memory, negative symptoms, hippocampal volume, and clinical/functional outcome in psychosis.146,217,221 Other factors, including duration of illness222 and age of onset184,223,224 have consistent negative effects on memory, whereas medications225 and cannabis use226 show equivocal results. Based on those results, we expect sex and duration of illness to act as moderators, but will also investigate additional variables (e.g., gender, age of onset, cannabis use) emerging from the prior PLS.

Subtyping Approach using SuStaIn

To assess the translational potential of our mediation model, we will employ SuStaIn147 in the full sample (patient and control data), which combines clustering and disease progression modeling into a unified framework and has been used extensively in neurodegenerative disorders. Building on an event-based disease progression model employing non-parametric mixture modelling,227 recently updated to combine neuroimaging and clinical data in Parkinson’s disease,154 we aim to employ z-score SuStaIn147 which allows for the assessment of severity in addition to event-based abnormalities. Z-score SuStaIn requires control data as the baseline for z-scoring and leverages the heterogeneity of cross-sectional data to learn the sequence of abnormalities (earlier/later events) and their severity (in z-score deviations from control norms) in a set of disease-relevant features (as a simple example: brain alterations followed by cognitive deficits followed by impaired functioning) and the probability of this sequence in each individual. The sequence of alterations is derived in a data-driven fashion and not anchored in our proposed model. This approach holds the advantage that SuStaIn can identify progression patterns in addition to our model, and will extend our mediation results with a temporal component, providing a data-driven lens to test whether results align with our hypothesized model.158 Incorporating our relational memory model into SuStaIn will thus allow us to infer subtypes of disease progression through our neuroimaging (hippocampal centrality), cognitive (relational memory, social cognition), and clinical (negative symptoms, functional outcome) markers (Figure 4e). The best number of fitting subtypes will be identified through the Cross-Validation Information Criterion (CVIC), a SuStaIn-specific measure of model fit as well as log-likelihood estimates.147 Hypotheses 2a and b will be supported if we identify a progression pattern aligned with our model, and not supported if this is not the case.

Sex and Gender-Based Analysis

When recruiting patients, we will seek to achieve a sex distribution that is reflective of demographics in clinical practice. All participants (patients and controls) will be asked both their sex assigned at birth and their current gender identity and that data will be reported systematically as suggested by Clayton and Tannenbaum.228 Gender will be operationalized as a categorical variable as recently proposed by Lindqvist et al.185 This approach provides a balance between taking existing gender diversity into account while assigning participants into gender categorizations suitable for statistical analyses. For our analyses, sex will be examined as a moderating factor, and we will explore associations with gender identity to determine whether including this factor as a moderator is warranted.

Sample Size Calculation

Sample size determination for basic group differences (t-test) was calculated with GPower, using a one-tailed test with an expected medium effect size of d = .5, consistent with our previous findings70 and the literature. We estimated that 120 participants would be required to detect a medium effect at a power of .90. To determine the appropriate sample size for our PLS and mediation analyses, we incorporated effect sizes from our previous mediation findings and preliminary data into two software packages, the Generative Modeling of Multivariate Relationships229 and Monte Carlo Power Analysis for Mediation Models.230 We estimated that the sample size required to detect a medium effect at a power of .90 would be 300 and 230 participants, respectively. In addition, to address generalizability of our findings, we will assess the accuracy of out-of-sample prediction of our models using k-fold cross-validation by splitting the patient sample into train (n=225) and test (n=75) sets 100 (k) times and evaluating R,2 as done previously.231 For SuStaIn, our sample compares well with those that have been used to test this approach in neurodegenerative cohorts.147,154

Open Science

The data will be stored and made accessible through the CRISP (Comprehensive Research into Schizophrenia and Psychopathology) databank of the Douglas Research Centre. The neuroimaging data will be defaced with the tool ‘pydeface’ and will be made available in nifti format following the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS). In addition, all headers will be anonymized and no personally identifiable information (PII) (i.e., sex, age) will be included in the neuroimaging files. For the behavioural data, PII (i.e., birth date, decimals following age) will not be made available, and PII collected throughout the semi-structured interviews (i.e., workplace) will be redacted as well. The overall access to the databank is restricted, and researchers must request access to the databank on an individual basis, with data made available following review and approval by the databank committee. A requirement for data access is ethical approval for their research by their host institutes.

Limitations

We need to consider two main limitations of the proposed study. First, our proposed model of psychosis does not necessarily provide a comprehensive model of psychosis overall. More precisely, we focus on cognitive components of psychosis, their potential foundation in the hippocampus, and their impact on negative symptoms and functioning. We acknowledge that this model does not consider positive symptoms or other neurodevelopmental factors contributing to psychosis. Second, the machine learning approach is based on monotonous modeling of the illness. SuStaIn was first developed in neurodegenerative illness, where a consistent decline of considered variables is innate to the disease. In this context, the algorithm was developed to model progression patterns under the assumptions that markers deteriorate but do not necessarily improve. This assumption is challenged by the episodic nature of mood and psychotic illness and, depending on the marker, might not be suitable to fully capture the progression of the illness. As our work is amongst the first to consider SuStaIn in a multiscale context of mental illness, these findings will nevertheless assist in defining patterns of illness severity across the variables of our model in the sample, and contribute to the interpretation SuStaIn in psychosis and its current limitations in mental illness. As all code will be made publicly available, our framework will allow for external researchers to contribute to the algorithm to better meet the reality of disease dynamics in psychiatric illness.

Strengths & Impact

We propose a model of psychosis, relating multimodal hippocampal dysconnectivity and relational memory as the foundation of poor functioning in psychosis for the first time. This hypothesis- and data-driven approach to investigate and validate the model in a sample of 300 patients with psychosis and 150 non-clinical controls holds relevance across several domains. From a clinical perspective, this model outlines the central role of the hippocampus and relational memory deficits in predicting functional outcome in psychosis across stages of illness. To date, there are no studies to our knowledge which directly address the relationship between the brain (and hippocampal connectivity specifically), cognition and their influence on functioning. While we previously provided evidence for a subtype of individuals with psychosis which shows reduced hippocampal connectivity prior to impaired episodic memory and functioning,158 no mediation analyses controlling for potential moderators has ever been conducted. The validation of our model could thus assist in guiding the development of more holistic interventions for improving quality of life. Novel treatment approaches, such as cognitive remediation, have proven successful in improving memory, functioning, and negative symptoms232 while targeting the brain.233 Our model thus paves the way for the implementation of such treatments while also informing the development of novel and innovative memory interventions and provides alternate paths of treatment which can alleviate the burden of cognitive and negative symptoms of psychosis.

Our sophisticated machine learning approach will assist such treatment efforts by providing metrics for individuals who are most likely to benefit from treatment at a specific point in their illness. Our approach offers potential for precision prognostication and guidance for implementing treatments, such as cognitive remediation, in a preventive capacity. In this context, our results will be central for evaluating the potential of data-driven staging approaches (such as SuStaIn) to be mapped onto traditional clinical staging models (such as McGorry et al.148). These clinical implications are extended through our innovative measures of multimodal hippocampal network connectivity. While often considered in solitude, our model considers the hippocampus in its role as a coordinator of cognitive and social behaviours in tandem with higher-order brain regions. By addressing this relationship across neuroimaging modalities, we may be able to capture the additive effect234 of hippocampal structure and function on the progression of psychosis. Lastly, our approach might yield a translational component by being applicable in mental disorders in which the hippocampus and memory are implicated, such as depression,160,161 allowing for the transdiagnostic assessment of biomarkers.

A central component and strength of this protocol is promoting open science principles and making our dataset publicly available to other researchers in the field. To date, such deeply phenotyped clinical neuroimaging samples are often not openly available, rendering our efforts a major stepping stone towards implementing open science principles in psychiatry. Such initiatives are key drivers of maximizing impact in the field, promoting forward-thinking, and facilitating discovery. Lastly, we hope to promote research into the neural and cognitive underpinnings of psychosis on a global scale by allowing for large-scale collaborative endeavors.

Timeline

From our previous collective experience, we expect to assess 70-80 patients and 35-40 controls per year across the three sites over the 5-year period (accounting for an attrition rate of 10-15% which is typical for such cross-sectional studies). This project has been funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and recruitment began at the Montreal site in summer 2024 and is currently ongoing at all sites. We have developed several strategies to maximize participation in our studies and limit attrition. This includes the use of a mock MRI scanner to habituate participants to the scanning process. Maintaining quality in assessment and calibration across sites represents a potential challenge, but we will prioritize strategies that will enhance the quality of our data across sites (i.e., through harmonization procedures).

Knowledge Transfer

Our knowledge transfer plan will target academics and practitioners in the field of mental health. On the academic side, we aim to make our dataset available to all researchers. This will be accomplished by publicizing our database at schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Schizophrenia International Research Society; International Society for Bipolar Disorders) and brain imaging (Organization for Human Brain Mapping) conferences. Further, working with the Open Science team at the Douglas Research Centre we will organize a series of academic events to bring exposure to our initiative. As we aim to make the dataset available within an ethical open science framework as well as all code used for analysis, we hope to allow for knowledge transfer to increase reproducibility and accessibility for large-scale analyses. On the clinical side, and as part of a funded initiative on the development of a learning platform for practitioners,235 we will develop a series of training modules on the importance of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, and how they relate to psychopathology and brain structures. We will present information on cognitive remediation, which is effective in increasing memory and functioning, while decreasing negative symptoms.232 Training modules will be made available to practitioners from our three institutions and more broadly as part of accredited professional development activities. Moreover, we hope to define the scope within which data-driven stages could complement traditional clinical staging models,147 and potentially add a predictive modeling component to these theoretical frameworks. Finally, this work can inform the development of innovative memory interventions as we have been spearheading in the last few years.236,237

Author Contributions

Jana F. Totzek: conceptualization, writing - original draft, visualization; M. Mallar Chakravarty: conceptualization, methodology; Synthia Guimond: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review & editing, resources; Stephan Heckers: conceptualization; Ridha Joober: conceptualization, writing - review & editing ; Carolina Makowski: conceptualization, methodology, writing - review & editing; Mahesh Menon: conceptualization; Bratislav Misic: conceptualization, methodology, writing - review & editing; Delphine Raucher-Chéné: conceptualization, writing – review & editing, writing - original draft, methodology, resources; Jai L. Shah: conceptualization, writing - review & editing; Todd S. Woodward: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review & editing, resources; Katie M. Lavigne: conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft, writing – review & editing, visualization, supervision, resources; conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft, writing – review & editing, supervision, resources, funding acquisition.

Code Availability Statement

The code for all analyses and processing steps as well as the data will be made publicly available upon completion of data collection and analyses. Code for the RiSE task can already be found here:

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ZEJ5W.

Acknowledgements

We thank the research coordinators and assistants across sites, as well as the programmers of the RiSE task and the MRI technical staff for harmonization. In addition, we thank the clinical staff and coordinators for recruitment. We also thank Karyne Anselmo for her support in preparing study related documentation and the ethics approval.

Funding Sources

We would like to thank the Canadian Institute of Health Research and the reviewers for funding this project (#480695). MMC holds salary awards from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé and reports funding from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Weston Brain Institute, Healthy Brains Healthy Lives and the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. SG holds a salary award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé and funding from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. CM holds funding from the National Institutes of Mental Health (R00MH132886) and the Brain Behavior Research Foundation (grant number 31876). JLS holds a salary award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. KML holds a salary award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé, and funding from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded to the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University (2b-NISU-22). ML holds salary awards through the James McGill Professorship, the Canadian Institute of Health Research and the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. JFT reports receipt of the Canadian Network for Research in Psychosis and Schizophrenia Graduate Studentship.

Conflicts of Interest

SG reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada) Ltd. RJ served as member of advisory board committees and speaker for Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Sunovian, Janssen, Myelin and Associates, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Shire, and Perdue, and received grants from Janssen, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, and HLS Therapeutics Inc. KML reports personal fees from Otsuka Canada, Lundbeck Canada, and Boehringer Ingelheim. ML reports grants from Otsuka Lundbeck Alliance, diaMentis, Hoffman-La Roche, personal fees from Lundbeck Canada, personal fees from Otsuka Canada, grants and personal fees from Janssen outside the submitted work. All of these disclosures are unrelated to the present study and all other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.