Introduction

Open data is now central to neuroscience, creating new possibilities for increased transparency and meaningful collaboration in research. As datasets expand and become more complex, building infrastructure for ethical and accessible data sharing, as well as data longevity, has become increasingly essential. Open data platforms have the potential to significantly enhance scientific reproducibility as well, which is an urgent need given that a 2015 study estimated $28 billion1 is spent annually on biomedical research that cannot be replicated, and concerns regarding false research findings have been growing in the scientific community.2,3 These platforms also hold the potential to increase innovation through secondary analyses, meta-science, and machine learning applications that will allow researchers to build on the work of others. As the field embraces open science, a critical question remains: How well are our current platforms meeting these demands?

Databases like the Neuroimaging and Electrophysiology Metadata Archive and Repository (NEMAR)4 aim to facilitate transparency and reusability of data, particularly in neuroscience. NEMAR operates as a web-based gateway to data housed within OpenNeuro,5 a repository originally developed for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data based on the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standards. OpenNeuro has since expanded to include all types of human neuroimaging data for which a BIDS standard is available, offering a centralized data-sharing platform. NEMAR specifically focuses on human neuroelectromagnetic (NEM) data, including electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and intracranial EEG (iEEG).4 All statements made in this paper about NEMAR equally apply to electrophysiology datasets hosted on OpenNeuro.

NEMAR’s integration with OpenNeuro enriches the platform by adding advanced features tailored to NEM data. These include automated data quality metrics, precomputed visualizations, and tools for annotating experimental events with Hierarchical Event Descriptors (HED), enabling precise data search and analysis. Furthermore, it connects directly to the Neuroscience Gateway (NSG),6–8 leveraging the high-performance computing infrastructure of the San Diego Supercomputer Center to support large-scale data processing and analysis without requiring users to download datasets. Academic researchers can get an account on the NSG at no cost and run custom MATLAB or Python scripts, enhancing the flexibility and scalability of their analyses.4,9,10

The integration of data, tools, and computational resources facilitates advanced neuroimaging analyses and meta-analyses, making it easier for researchers to adhere to emerging standards for data formatting, identification, and annotation.11 NEMAR also works to address some of the root causes of the replication crisis, such as inconsistent reporting of methodologies, limited accessibility to raw data, and lack of tools for cross-study analysis.1,12

Despite the growing number of datasets hosted on NEMAR, only limited analysis has been conducted to assess their composition, quality, or adherence to data-sharing standards.4,13 The present study systematically analyzes the datasets within NEMAR to assess dataset composition and coverage, identify areas of strength, and highlight potential gaps in metadata quality. Our goal is to provide a high-level overview of the current state of open neuroelectromagnetic data sharing on NEMAR, identify areas of strength and persistent limitation, and offer actionable insights to support more effective, equitable, and sustainable data governance in neuroscience.

Methods

This study drew from an initial pool of 306 datasets available on the NEMAR database as of August 2024. Some metadata, such as electrophysiology modality, was automatically pooled from the NEMAR and OpenNeuro databases. However, most metadata (Supplementary Table 1) was manually extracted from each dataset. Each dataset was systematically reviewed by a group of five students to extract and log key information into a dedicated spreadsheet (Supplementary Table 1). The extracted details included, but were not limited to, participant demographics (age range, type of subjects), dataset characteristics (dataset size, number of files, number of sessions, scans per session), and technical specifications (format, modality, additional modalities, number of EEG channels, and number of different imaging channels, adherence to the 10-20 system). Experimental parameters (type of data, modality of the experiment, type of experiment, tasks involved) and institutional data (first author, author affiliations, country of origin, multi-institution collaborations, publication date, references, funding sources, and ethics approval) were also logged.

The information was primarily obtained from the NEMAR database entries provided by the dataset authors. In cases where the uploaded data lacked sufficient detail, corresponding publications (when available) associated with the datasets were consulted to complete the missing information.

Modality of experiment, type of experiment, and type of subject data were catalogued free-form by interns on the team. Each dataset was categorized based on the modality used to collect it (e.g., Visual, Audio, Motor, Resting State, etc.) and experiment type, classified according to the task involved (e.g., Emotion, Decision, Attention, etc.). Given the inconsistency and high specificity of the initial inputs, authors TB, AR, and AD standardized the classifications by mapping detailed entries (e.g., “object recognition”) to broader categories (e.g., “Perception”), reclassifying entries to maintain consistency, enhance comparability, and achieve a balanced distribution across categories. They did the same for the modality of the experiment and the type of subjects.

Final categories for modality of experiment included: Auditory, Anesthesia, Motor, Multi-sensory, Tactile, Other, Resting State, Sleep, Unknown, Visual. Final categories for type of experiment included: Affect, Attention, Clinical/Intervention, Decision-making, Learning, Memory, Motor, Other, Perception, Resting-state, Sleep, Unknown. Final categories for type of subjects included: Alcohol, Cancer, Dementia, Depression, Development, Dyslexia, Epilepsy, Healthy, Obese, Other, Parkinson’s Disease, Schizophrenia/Psychosis, Surgery, Traumatic Brain Injury, Unknown.

After the data sets were logged, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to refine the dataset pool. A list of excluded datasets and the reason for their exclusion is available in Supplementary Table 2. Datasets were excluded if they involved non-human subjects, served as placeholders, were corrupted or incomplete, or did not comply with BIDS. Although all datasets on NEMAR are intended to be BIDS-compliant, dataset authors may use ignore flags to submit non-compliant datasets. Additionally, datasets were excluded if, even after performing research on the dataset and its associated publication, it was impossible to determine the locations of the channels, making it unusable. Based on these criteria, 18 datasets were excluded, leaving 288 datasets that met all requirements.

In our analysis, a single dataset may be divided into multiple datasets if different experiments are included in a single BIDS dataset. It is important to note that if all data corresponded to the same experiment, this division was not performed, for instance, in a learning task where the learning and testing phases are involved. However, if the experiment included distinct, unrelated sessions—such as eyes-open/eyes-closed resting data and unrelated task-based data — a split was applied, processing the original dataset as two separate datasets, each corresponding to one experimental condition. This allowed for a fine-grained analysis. In total, four datasets met this criterion, necessitating the creation of a new row for each distinct experiment (highlighted in blue shade in Supplementary Table 1), which resulted in analyzing 292 entries in total.

Python scripts were written to parse through the database (Supplementary Table 1) and perform data analysis. These analysis scripts have been released to the public and are available at the following link: https://github.com/sccn/nemar_paper_plot. Given that the databases were manually filtered and labeled by discrete criteria, software preprocessing was minimal and did not involve any modifications of the data itself. Descriptive analysis was performed in order to obtain relevant metrics, as further described in Results and Discussion. The Matplotlib and Plotly Python libraries were used to generate Figures 1-8 and provide data visualization upon the compiled NEMAR database.

Additional BIDS-compliant technical metadata associated with the NEM data were extracted from relevant studies to assess how frequently such information is reported. Metadata files were collected via web scraping from the publicly available OpenNeuro GitHub organization (https://github.com/orgs/OpenNeuroDatasets/repositories), and the proportion of repositories containing each relevant metadata element was quantified (Supplementary Table 3). All web-scraping and data analysis procedures were implemented in Python, and the corresponding scripts are available in the paper-associated GitHub repository.

Portions of this manuscript were prepared with the assistance of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. The tool was used for editorial purposes, including refining phrasing and structural editing to improve readability.

Results

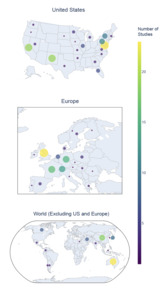

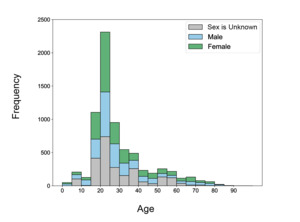

The majority of studies originated in the United States (US; 42.8%), followed by the United Kingdom (UK; 8.2%) and France (5.8%) (Fig. 1). Significant contributions (>10 studies) were also noted from Germany, Australia, Switzerland, and China. Within the US, the greatest number of studies came from Maryland (18.4% of US-based studies, 7.87% of total studies), California (15.2% of US-based studies, 6.5% of total studies), and New Mexico (15.2% of US-based studies, 6.5% of total studies), with additional significant contributions (>10 studies) from Pennsylvania and New York.

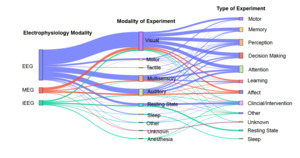

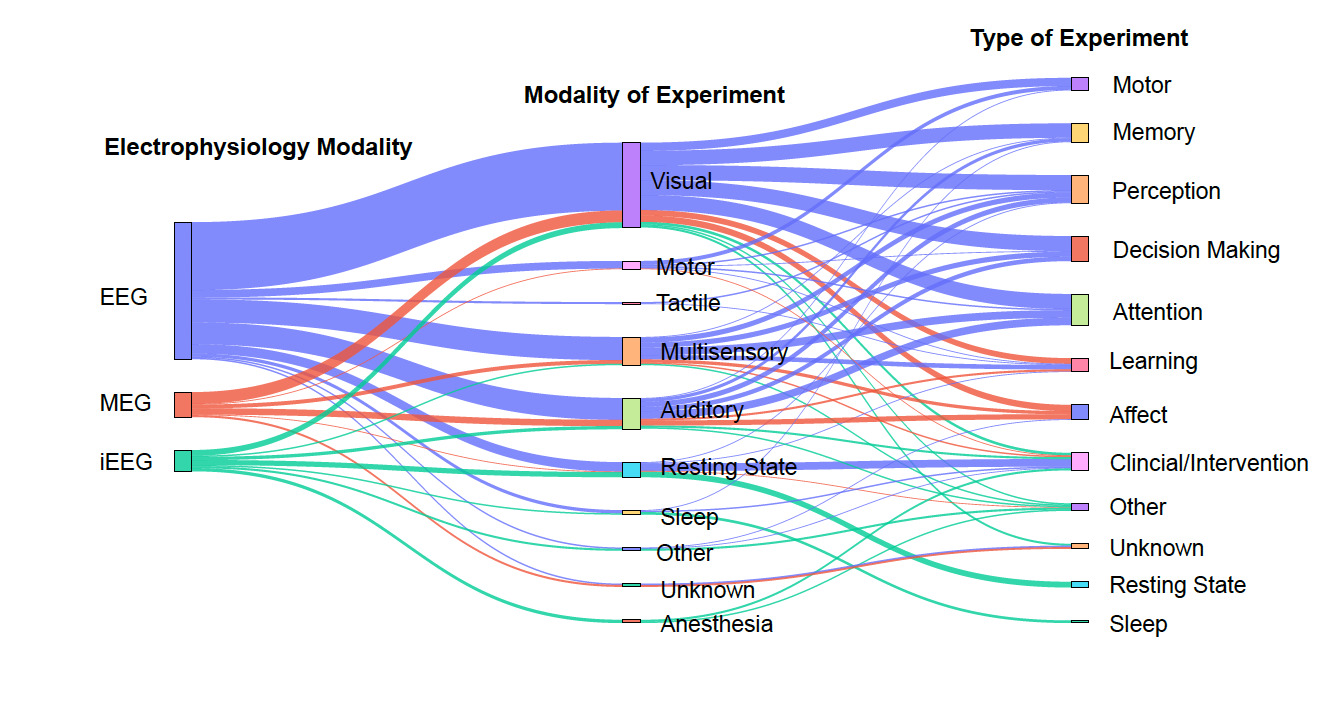

Figure 2 visually represents the relationships between primary electrophysiology modalities, modalities of experiment, and types of experiments in NEM research (see Methods). On the left, the primary modalities include EEG, MEG, and iEEG, with EEG appearing as the most commonly used modality, used in 75.34% of datasets. Notably, visual and motor experiments have strong connections, suggesting their prominence in neuroimaging studies, while memory, perception, and attention are widely studied across multiple modalities.

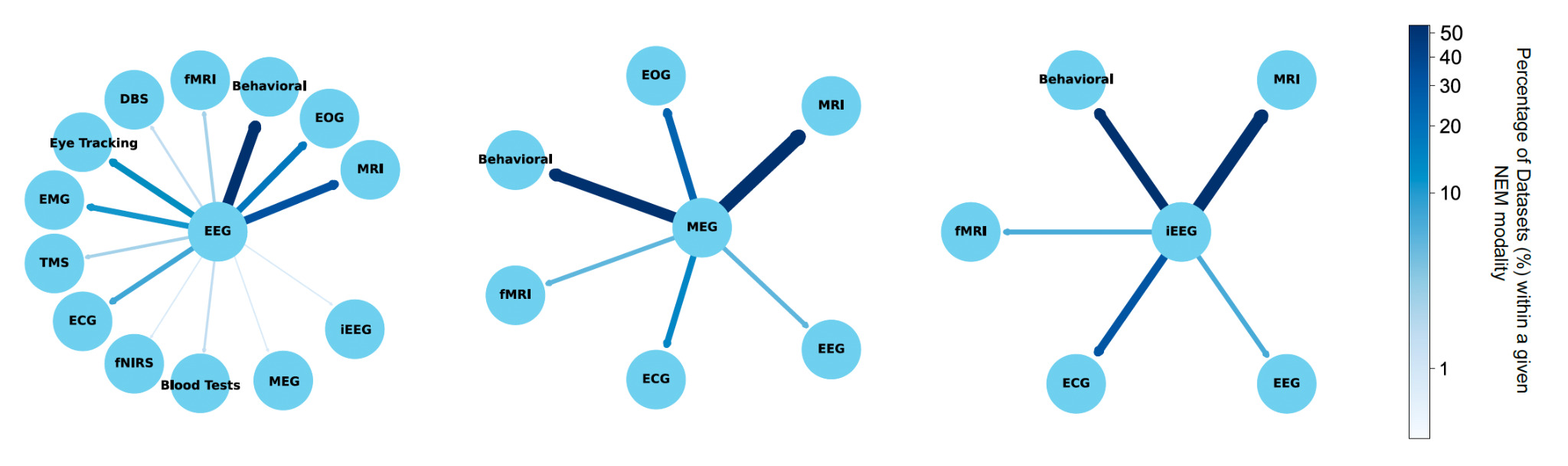

The selected studies often used multiple modalities in tandem, with Figure 3 demonstrating the most frequently used co-modalities. MRI was found to be the most prominent across all three graphs. EEG shows a strong association with behavioral testing, as 49 of 220 studies incorporating both modalities. MRI, EOG, and EMG were also commonly associated with EEG data. MRI was most commonly used as a secondary modality to MEG (20 of 40 studies) and iEEG (12 of 34 studies). These relationships highlight the complementary roles of different neuroimaging techniques in research and clinical applications.

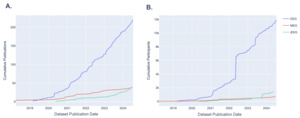

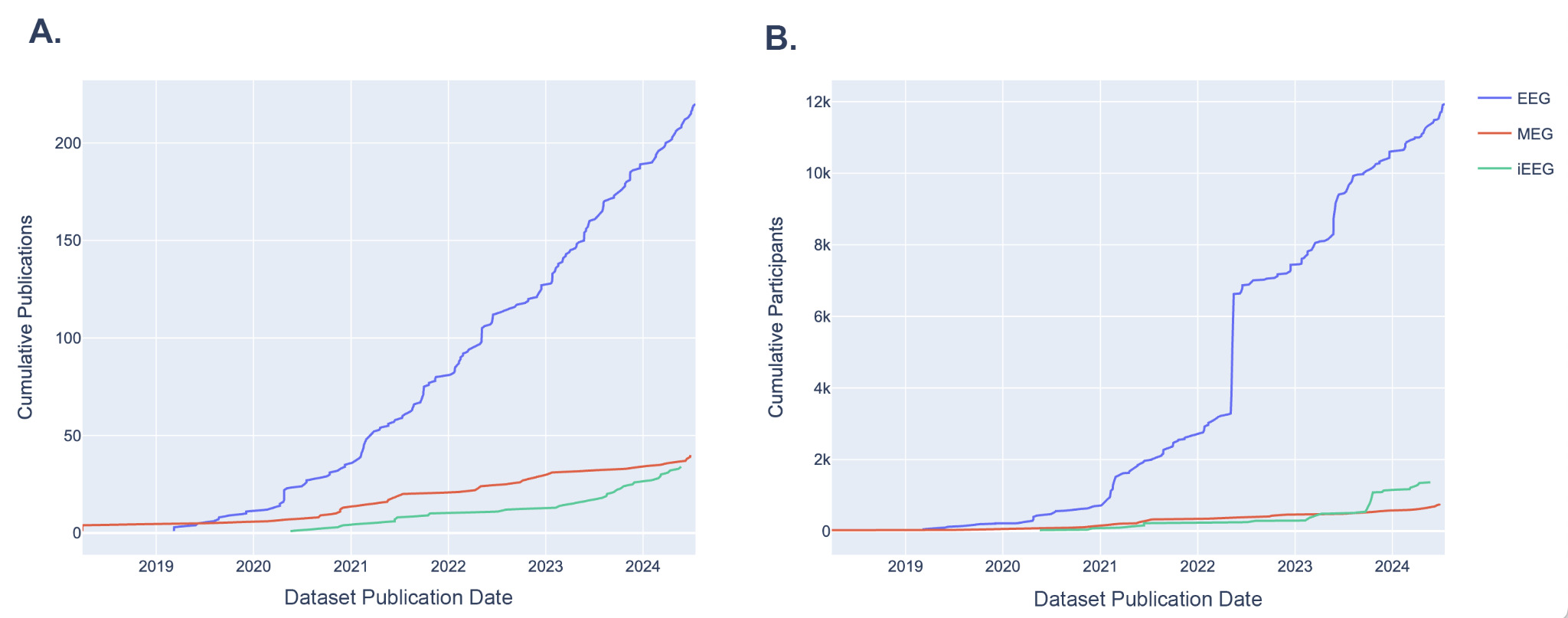

Since the establishment of NEMAR, the number of new EEG datasets uploaded each year has been steadily rising, from 11 new datasets added in 2019 to 62 new datasets added in 2023 (Fig. 4). MEG datasets have also been uploaded at an increasing rate, with an uptick in 2022, though comparatively lower than the number of EEG datasets uploaded. iEEG datasets also experienced increased uploads since 2023. Participant numbers have also been growing since the establishment of NEMAR, especially in EEG which nearly doubled in 2022 and continued to grow exponentially (Fig. 4B). The growing number of datasets and participants of these primary modalities uploaded to NEMAR demonstrates the database’s increasing utility as a centralized space for open-source data. Figure 4 is intended as a descriptive visualization of submission trends rather than a normalized growth analysis.

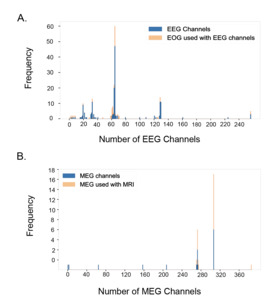

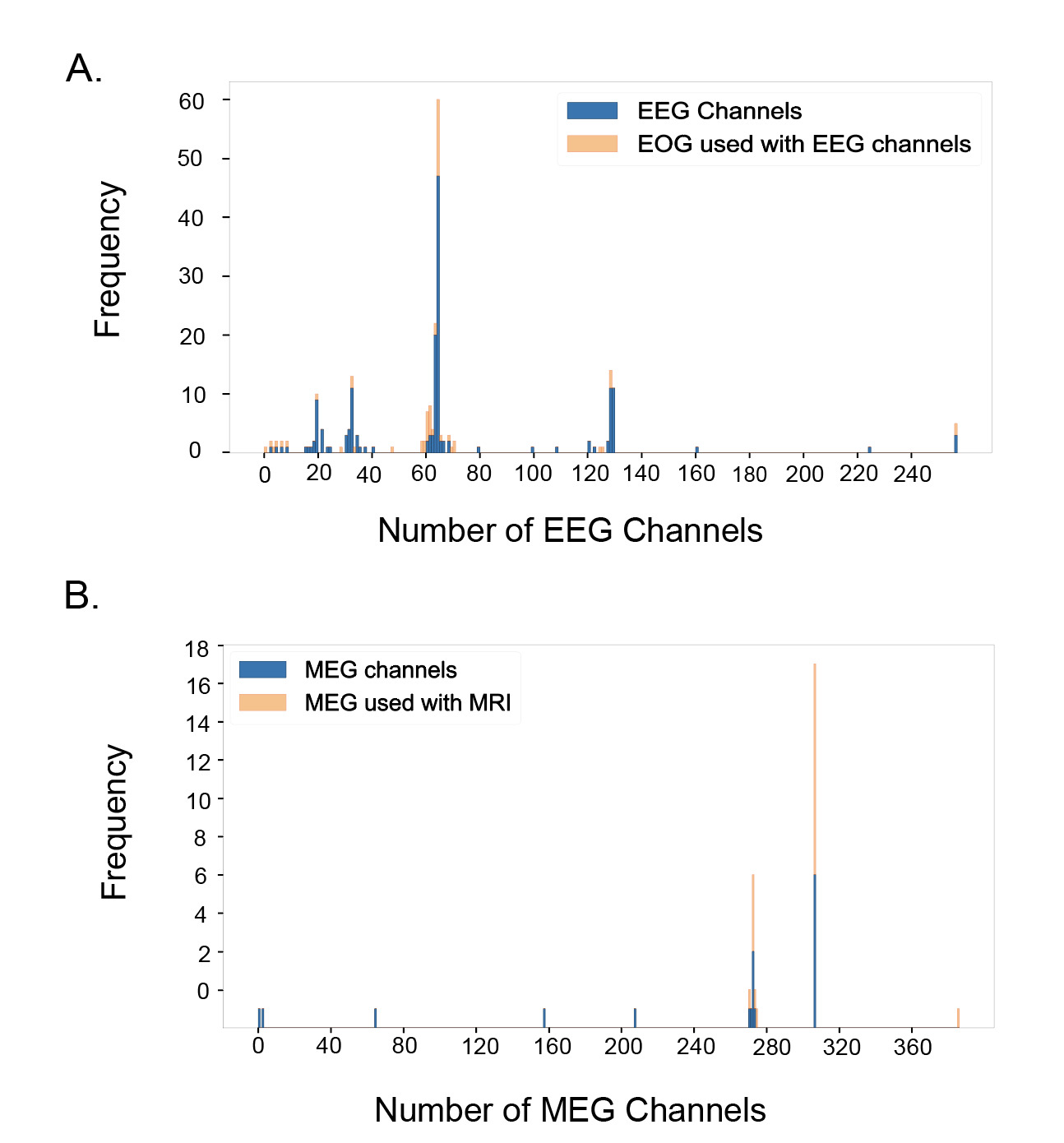

Figure 5A shows the distribution of EEG datasets by the number of channels used, along with the proportion of datasets at each channel count that also included EOG recordings. The most common EEG setup used 64 channels, found in 60 of the total 220 EEG datasets. Other spikes were also observed at 19 channels (10 datasets), 32 channels (13 datasets), 63 channels (22 datasets), 128 channels (14 datasets), 129 channels (11 datasets), and 256 channels (5 datasets). The proportion of EEG datasets that used associated EOG data was also observed by channel. At the designated spikes, the percentage of EEG data that simultaneously recorded EOG data was as follows: 10.0% at 19 channels, 15.4% at 32 channels, 71.4% at 61 channels, 9.1% at 63 channels, 21.7% at 64 channels, 21.4% at 128 channels, 0% at 129 channels, and 40% at 256 channels. There does not appear to be a strong correlation between the number of channels and the usage of EOG data.

Figure 5B presents the distribution of MEG datasets based on the number of channels used, along with the proportion of datasets at each channel count that also included MRI recordings–while EOG is the most common and relevant co-modality used with EEG, MRI is the primary co-modality for MEG. The primary spikes were observed at 272 channels (17 datasets, 76.47% used MRI), and 306 channels (19 datasets, 57.89% used MRI), which correspond to conventional SQUID-based MEG systems. In addition, a small number of datasets with substantially fewer channels (typically 20–80) can be observed in Figure 5B, reflecting recordings done with newer optically pumped magnetometer- (OPM) based MEG systems, which employ compact sensors that can operate without cryogenic cooling and allow for more flexible sensor placement as well as higher sensitivity and better signal quality.

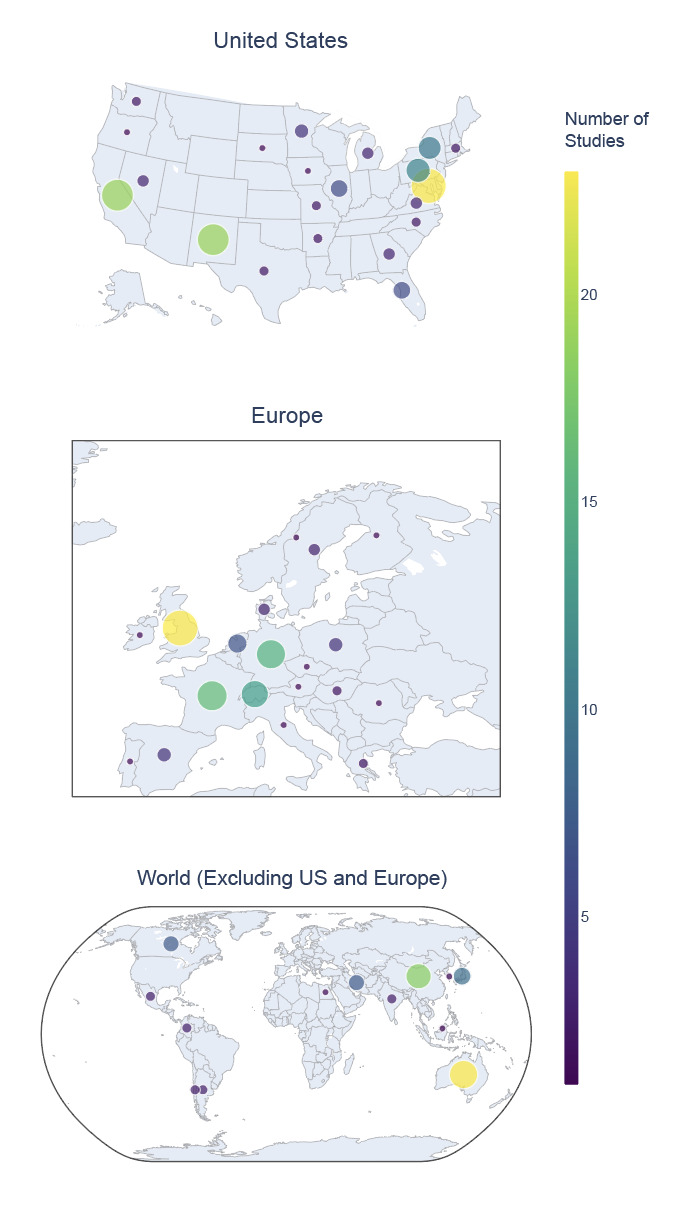

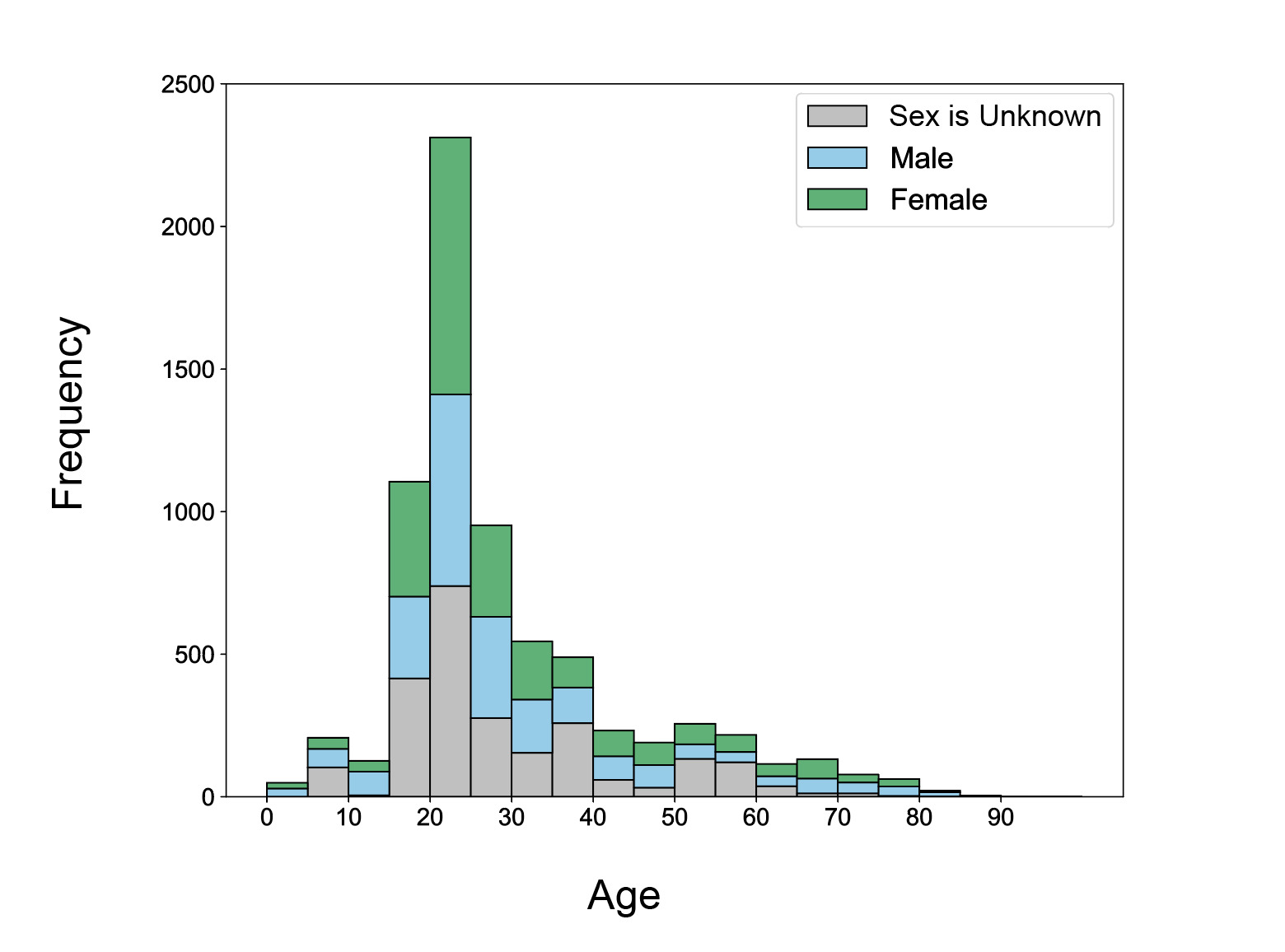

The ages of subjects in NEMAR datasets are skewed right (Fig. 6), with a spike at 20-25 years old, which makes up 2312 of 7093 (32.6%) of subjects. 4370 subjects (61.61%) were between 15-30 years old. Comparatively, only 885 subjects (12.47%) are at least 50 years old, demonstrating that most datasets assembled are created from younger populations. 52.93% of all participants with known sexes were female, while 47.05% were male. Only one participant across all NEMAR datasets was identified as non-binary and is not represented in the figure. Importantly, even when age is specified (69.18%), a large portion of subjects have unspecified sex, indicating missing metadata that may be relevant for data processing.

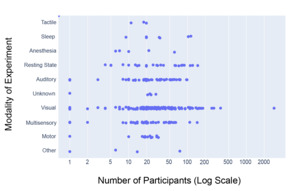

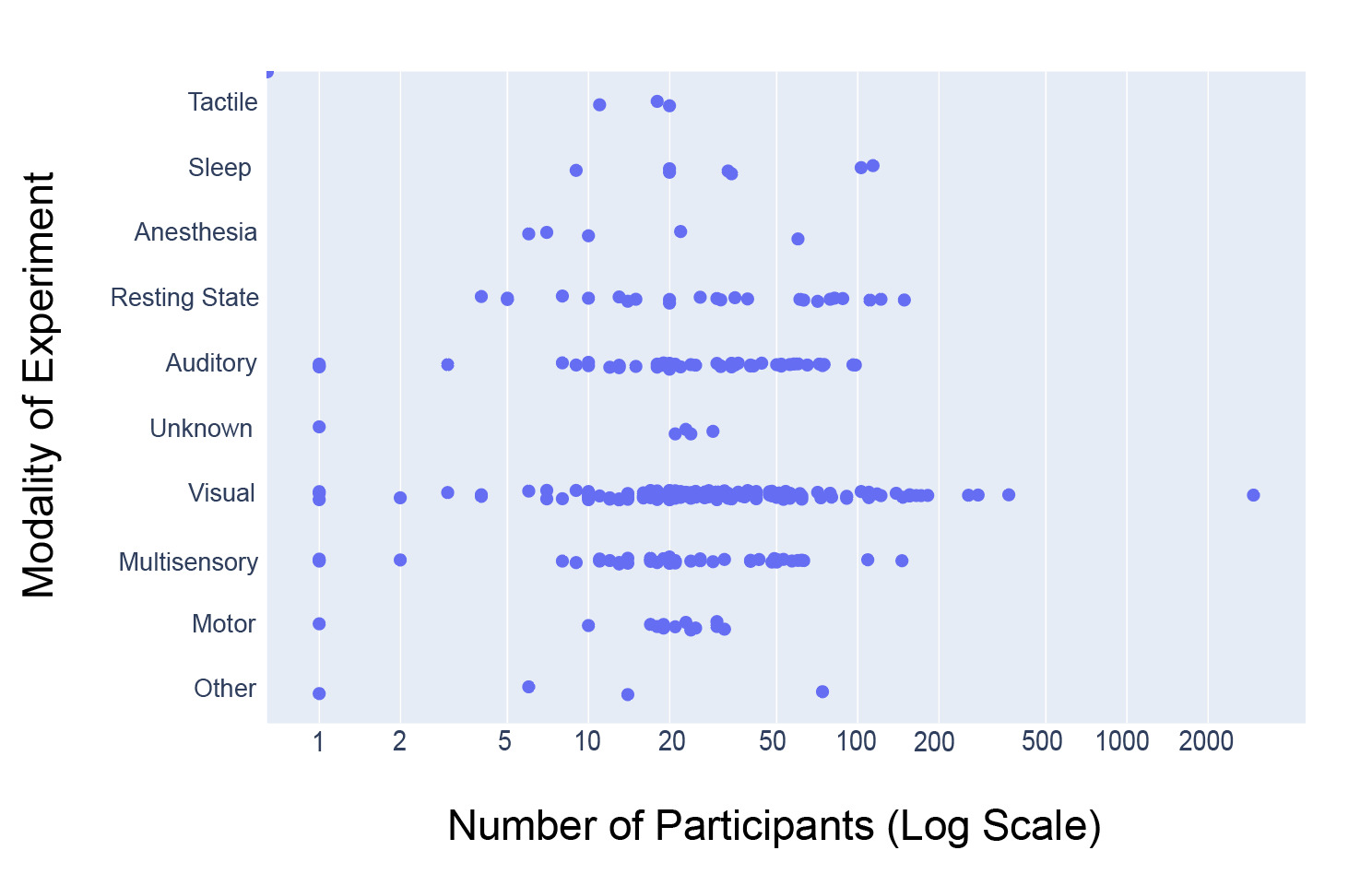

Figure 7 shows that, of the 14,033 participants analyzed, 9046 (64.5%) underwent experiments using visual modalities across a total of 136 datasets, which encompassed the largest modality category. The range of participants per dataset was also highest within the visual dataset, ranging from 1 to 2951 participants per dataset. The presence of the dataset with 2951 participants substantially increases the aggregate proportion of participants associated with the visual modality. However, because Figure 7 is intended as a descriptive summary of the data available in NEMAR rather than an inferential analysis, all datasets, including large-scale studies, were retained to accurately reflect the total scope of available data. Auditory (49 datasets, 1578 participants), Multisensory (45 datasets, 1359 participants), and Resting State (24 datasets, 1101 participants) were also comparatively large categories (arbitrarily defined as >20 datasets).

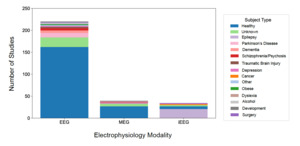

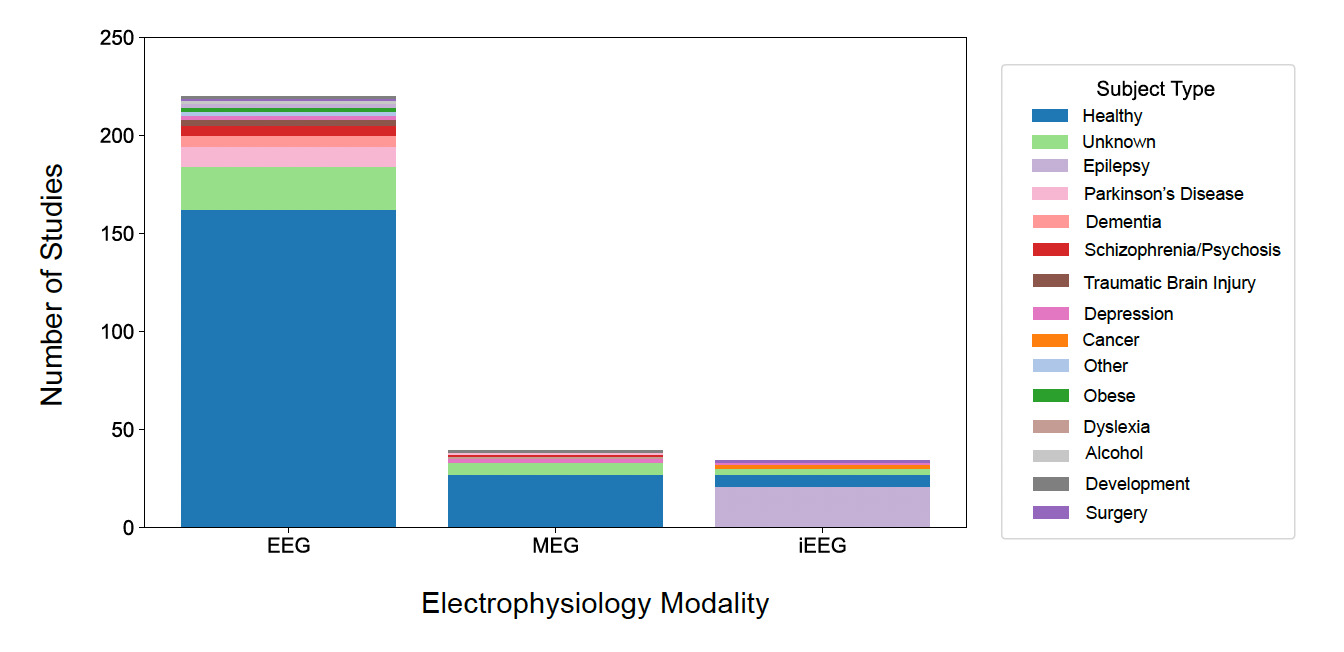

The NEMAR datasets were categorized by the type of participants from whom data were obtained (Fig. 8). Healthy participants are the most represented group across all modalities, particularly in EEG studies, with 66.32% of datasets obtained from healthy participants. Epilepsy (22 datasets) and Parkinson’s (11 datasets) were the only categories of non-healthy participants with at least 10 datasets. A notable portion of studies (31 datasets), especially in EEG and MEG, include subjects with unknown classifications.

In addition to the core dataset characteristics reported above, we examined several metadata fields relevant to open data practices. Regarding metadata transparency, 52.1% of datasets indicated a funding source, 65.1% provided documentation of ethical approval within the BIDS structure, and 57.5% included a reference to an associated peer-reviewed publication. 64.26% had author lists that included contributors from more than one institution, and 44.33% included authors affiliated with institutions in different countries. 39.73% of datasets were also hosted on the Brainlife platform. Information about study equipment and experimental procedures was variably reported across modalities. For EEG datasets, 23.2% specified the manufacturer of the electrode cap and 11.6% provided the specific cap model. In addition, 40.6% reported the manufacturer of the recording device, and 52.2% reported the specific device model. Among iEEG datasets, 50% indicated the manufacturer of the electrodes and 30% included the electrode model, while 95% reported the manufacturer of the recording device and 50% reported its specific model. For MEG datasets, all datasets specified the manufacturer of the recording device, but only 31.2% included the device model. Description of the task conducted was provided in 39.1% of EEG datasets, 75% of iEEG datasets, and 21.9% of MEG datasets, with the instructions given to the participants included in 5% of iEEG datasets, 18.8% of EEG datasets, and 6.2% of MEG datasets.

We also explored available platform usage statistics to address the “demand” side of the NEMAR repository. As of October 2025, Google Analytics data indicated approximately 2,500 active users and 2,400 new users during the previous month, with engagement spanning more than 60 countries. The largest numbers of users originated from China, the US, Singapore, Japan, Germany, Hong Kong, and India. Data from the public NEMAR Dataset Citation Dashboard (https://neuromechanist.github.io/dataset_citations_dashboard.html) show that, as of October 2025, 318 of 435 datasets (>70%) have been cited in peer-reviewed publications across electrophysiology, cognitive neuroscience, and neuroinformatics.

Usage data from the Neuroscience Gateway (NSG) provide additional context for NEMAR’s integrated computational resources. Since 2023, monthly NSG–NEMAR activity has ranged from 1 to 47 computational jobs per month, with 1–24 unique users depending on the period. Activity peaked in April and May 2024 (47 and 44 jobs, respectively), averaging approximately 2–4 jobs per user during those months. Across 2025, usage continued intermittently, with several periods of concentrated activity (e.g., 39 jobs in May 2025).

Discussion

This analysis of the Neuroelectromagnetic Data Archive and Repository (NEMAR) offers a critical window into the realized potential and remaining challenges of open neuroelectromagnetic (NEM) data sharing. As open science initiatives continue to reshape the landscape of neuroscience research, understanding how repositories like NEMAR are utilized and where they fall short is essential to building a data ecosystem that is reproducible, inclusive, and scientifically valuable. Our findings highlight NEMAR’s emergence as a rapidly expanding platform that supports multimodal data integration, while also surfacing persistent issues related to metadata completeness, population representativeness, and structural support for clinical datasets.

One of the most encouraging trends is the sharp increase in the number of datasets submitted to NEMAR/OpenNeuro since its inception. EEG datasets, in particular, have seen substantial growth. Our analysis reveals that 62 EEG datasets were uploaded in 2023 alone, compared to 11 uploads in 2019 (Fig. 4), aligning with global trends in the democratization of EEG research tools and the relatively lower cost of EEG acquisition compared to other neuroimaging modalities.14 Equally promising is the diversity of experimental modalities and co-registered data. The co-occurrence of EEG with behavioral data, MEG with MRI, and iEEG with structural imaging (Fig. 3) demonstrates that multimodal data sharing is not only feasible but increasingly common. This observed trend paves the way for future integrative neuroscience, where large-scale meta-analyses and machine learning pipelines can harness the richness of complementary datasets.

Beyond core experimental characteristics, we also observed encouraging patterns in authorship and collaboration. A majority of BIDS datasets (64.3%) included contributors from more than one institution, and 44.3% featured authors affiliated with institutions in different countries. Regarding platform interoperability, 39.7% of datasets were also hosted on the Brainlife compute resource, and all were available on the associated NSG compute resource, indicating growing integration between NEMAR and external computing infrastructures. The usage statistics presented are also a promising indication of how NEMAR is being accessed and utilized by the research community. The global distribution of users and the high proportion of datasets cited in peer-reviewed publications suggest meaningful engagement with shared data. The integration of NEMAR with the Neuroscience Gateway (NSG) further demonstrates that a subset of users are leveraging linked computational resources to analyze datasets directly through the platform. Nevertheless, this data represents aggregate measures and does not capture individual user behavior or the specific scientific outcomes resulting from data reuse. As NEMAR does not require user identification for browsing or downloading, only limited information on user demographics or affiliations can be inferred. Future efforts will focus on expanding these analytics through additional mechanisms, such as questionnaires, targeted surveys, and optional reporting features, to support a more comprehensive evaluation of the repository’s use and impact.

Despite these positive developments, challenges remain, particularly in metadata quality and completeness. Many entries contain inconsistent formatting, incomplete metadata, or missing documentation on experimental procedures, recording systems, or electrode locations. Only 52.1% of datasets indicated a funding source, 65.1% included documentation of ethical approval, and 57.5% were linked to an associated peer-reviewed publication. Less than 40% of the EEG and MEG datasets gave detailed task descriptions, across all modalities less than 20% of datasets reported participant instructions, and there was also a lack in reporting on specific hardware models used in the study across the board. All of the metadata listed above is extremely important for transparency, accountability, and especially reproducibility.

To explain this inconsistency of metadata reporting we can look to the “required” versus “recommended” fields of the NEMAR. While standards such as BIDS provide a robust framework for metadata organization, not all fields are required for submission, and several that are merely recommended are frequently left unfilled in practice, and this partial adherence contributes to uneven metadata completeness across NEMAR. A more granular breakdown of required versus optional fields can be found in the BIDS documentation (https://bids-specification.readthedocs.io/en/stable/modality-specific-files/electroencephalography.html). These patterns suggest that current distinctions between required and optional fields may warrant re-evaluation, as even non-mandatory metadata often play a critical role in enabling data reuse and reproducibility. This issue is not unique to NEMAR; metadata inconsistency is a known limitation across open repositories and has been cited as a major barrier to data reuse.15 Strengthening metadata standards—through automated completeness checks, structured submission fields, and clearer guidance on minimal reporting requirements could significantly improve the usability and trustworthiness of shared datasets.

Our findings also revealed a marked underrepresentation of clinical populations in NEMAR. More than 66% of the datasets were collected from healthy participants (Fig. 8), with only epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease represented in at least ten datasets. Given the centrality of EEG and MEG in both clinical and translational neuroscience, the lack of clinical population data is a missed opportunity to support biomedical discovery through open data. Ethical and privacy concerns are a well-documented barrier to clinical data sharing,16,17 and re-identification concerns and evolving consent requirements often limit researchers’ willingness or ability to share data. Even when fully anonymized, electrophysiological data may contain subject-specific features that challenge traditional de-identification protocols. In many cases, researchers may lack access to institutional guidance, legal clarity, or secure platforms necessary for sharing sensitive datasets – especially under fully open licenses such as Creative Commons 0 (CC0) of OpenNeuro/NEMAR. There are limited datasets with CC-BY licenses (e.g., the Healthy Brain Network datasets, ds005505-ds005516) on NEMAR, to facilitate data sharing even with less permissive licenses. NEMAR is planning to roll out wider support for hosting such permissive licenses, including the CC-BY and MIT families on a case-by-case basis. De-identification pipelines and modular data use agreements could mitigate these concerns while upholding participant protection for clinical data. In fact, an OpenNeuro-related effort in Europe (https://openneuropet.github.io/) requires researchers to sign waivers to access data.

Another notable gap in the data is age representation, with subject age distributions being heavily skewed toward young adults, with more than 60% of participants between the ages of 15 and 30 (Fig. 6). This is likely due to convenience sampling in university-based studies and underscores the need to expand demographic inclusivity. The near absence of older adults is particularly concerning given the increasing interest in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Future funding and data collection initiatives should incentivize inclusive recruitment strategies to support greater generalizability of shared findings. Geographic representation within NEMAR was moderately diverse, with datasets originating from over 20 countries. However, nearly half of all datasets came from the United States (Fig. 1), reinforcing known disparities in global data representation.

Beyond age and geography, demographic variables such as race, ethnicity, and education level are not currently captured within NEMAR submissions. This omission reflects a broader pattern across neuroimaging: a systematic review over a decade found that the majority of neuroimaging studies do not report demographic variables beyond age and sex, limiting interpretability and contributing to demographic opacity in open data.18 That trend illustrates a field-wide gap: without structured reporting of race, ethnicity, and education, it remains difficult to evaluate the representativeness of datasets or to detect biases driven by overrepresentation of WEIRD populations.19 To address this limitation and strengthen open science, future repository standards and submission guidelines should encourage the inclusion of structured, de-identified demographic fields, particularly race, ethnicity, and education level, alongside existing age and sex variables.

Insight into the underlying reasons for these gaps will be needed to improve the next iteration of open neuroscience infrastructure. The time and technical expertise required to convert data to BIDS or HED format can be daunting, especially for multimodal datasets. To aid in this, we are currently developing an automatic AI-based tool to enable data annotation with ease. Many researchers also remain unfamiliar with the broader impact that reusable, well-annotated datasets can have across disciplines, and academic recognition for data sharing remains low. Datasets are not often cited independently, and few mechanisms exist for rewarding contributions of high-quality data in hiring, promotion, or funding decisions.

Addressing these challenges will require concerted investment in both infrastructure and scientific culture. Continuing to develop user-friendly tools that simplify dataset formatting, validation, and submission (https://github.com/sccn/EEG-BIDS), paired with clear ethical guidelines for sharing clinical and nonclinical data, will be essential. Controlled-access frameworks can offer a secure alternative where fully open sharing is not feasible. Yet infrastructure alone is insufficient. A broader cultural shift is needed, particularly among early-career researchers, to reframe data stewardship not as a peripheral task but as central to research integrity and scientific progress.

The FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) have emerged as a cornerstone in this shift, offering a structured vision for how data should be organized and shared to maximize long-term impact.20 Initiatives like the International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility (INCF) are already advancing this agenda through training programs, technical resources, and community standards.20 While challenges remain around metadata standardization and ethical compliance, adherence to FAIR is a promising pathway toward more open, rigorous, and collaborative neuroscience. Previously, NIH-funded neuroimaging data were generally required to be submitted to the NIH Data Archive (NDA), particularly under institutes such as NIMH and NINDS. However, as of January 25, 2023, with the implementation of the new NIH Data Management and Sharing (DMS) Policy, researchers are permitted to deposit their datasets in approved domain-specific repositories, such as OpenNeuro and its affiliated platform, Neuroimaging and Electrophysiology Materials Archive. This change is intended to foster broader data accessibility and reuse by encouraging the deposition into repositories that align with community standards and promote FAIR principles.

The financial and environmental sustainability of open data infrastructure is an important consideration as well as such platforms continue to expand. NEMAR currently operates on a dedicated web server and a 200 TB storage system hosted on Amazon Web Services (AWS), supported in part through Amazon’s cloud access program. Based on commonly cited estimates for cloud data storage (approximately 0.5–1.0 kg CO₂ per GB per year), the annual carbon footprint of NEMAR is roughly 100–200 t CO₂. While this represents a measurable environmental cost, the repository’s facilitation of data reuse offsets a far greater carbon and financial burden associated with redundant data collection. For instance, reproducing the 14,033 participant recordings detailed in this paper that are hosted on NEMAR would entail emissions several orders of magnitude higher—likely in the hundreds of thousands of tons of CO₂—alongside multimillion-dollar research expenditures. Maintaining open repositories therefore yields a net reduction in both cost and carbon impact. Nevertheless, long-term sustainability requires proactive planning: continued support from commercial hosting providers cannot be assumed indefinitely, and diversification of hosting models will be essential to preserve FAIR accessibility should current cloud arrangements change.

Conclusion

Platforms like NEMAR are shaping the future of open, collaborative neuroscience by providing scalable, transparent infrastructure for data sharing. Our audit highlights both progress and ongoing barriers, showing that while shared neuroelectromagnetic data are expanding, full realization of their potential remains limited. Open, standardized, and ethically shared data can drive machine learning, meta-analyses, and clinical innovation, but achieving this future requires more than infrastructure — it demands cultural change, better tools, and incentives for transparency. NEMAR offers a strong foundation, but realizing the promise of open science will depend on collective investment from researchers, institutions, and funders.

Code and Data Availability Statement

All code used for data processing, statistical analysis, and figure generation is available on GitHub at the following link: https://github.com/sccn/nemar_paper_plot. The datasets analyzed in this study are provided in the repository under the /data directory. Researchers may reproduce or extend the analyses using the included scripts and documentation.

AI Use Statement

Portions of this manuscript were prepared with the assistance of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. The tool was used for editorial purposes, including refining phrasing and structural editing to improve readability.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by NIH grant R24MH120037-05, BRAIN Initiative Resource: Development of a Human Neuroelectromagnetic Data Archive and Tools Resource (NEMAR).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.