Introduction

Sharing research data is a core pillar of open science. In neuroscience, open data is proving crucial to the field’s massive efforts towards building a comprehensive understanding of normal brain function as well as discovering the mechanisms underlying and treatments for a host of devastating neurological and psychiatric disorders. The re-use of existing data is accelerating the speed of discovery, enhancing statistical power (by pooling data across studies), and improving the quality of scientific research via increased transparency, reproducibility and replicability. Despite these many benefits to the neuroscientific endeavor, there is a tension with participant rights, due to increasing concerns about data protection and privacy of neurological information (neurorights1). Ethical research frameworks emphasize the need to protect participant rights to privacy and confidentiality. As such, it is crucial that participants make informed choices based on clear information about the future uses of their data, the protection of their identity, and the risks of re-identification. In this paper, we discuss the evolving ethics of practicing open neuroscience in the Canadian context, from the perspective of Baycrest Academy for Research and Education (BARE), a small but prominent neuroscience research institute based in a Toronto geriatric hospital. We report the results of a systematic analysis of study protocols that reveals data sharing trends and participant consent rates at the institute, setting a benchmark for open science consent practices in Canadian neuroscience research institutes.

Ethical Open Neuroscience in the Canadian Context

In Canada, scientists must comply with the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (known as TCPS-22). Although this policy aligns with international ethical standards, the interpretation of the guiding principles has some unique implications for the practice of open data sharing. Participant autonomy in research must be respected whether they are directly involved in research or their data is being used in secondary research. Researchers must obtain participant consent to retain their data for future use – including in studies by the researchers themselves that diverge from the stated research questions in the original consent. Research Ethics Board (REB) review is required before re-using data, even if those data were originally collected outside of Canada. Participants should have, at the time of data collection, provided consent for their data to be re-used; if not, researchers may be required to seek consent for re-use. An emerging ethical issue under the TCPS-2 framework is that data shared in online repositories is not usually accompanied by details regarding participants’ original consent to re-use their data.3

Privacy includes the right to determine and control how data about oneself will be used. To that end, researchers must provide participants with sufficient information about data sharing to facilitate as complete an understanding as is reasonably possible, including the intended audience and methods of sharing, whether they will be asked to provide separate consent for future use, the extent to which future uses are known, and the possible risks (Articles 3.2 and 3.13, TCPS-22). Typically, not all future uses are known - especially if the data is to be shared for re-use by others - and the risks associated with data sharing cannot be fully known as new risks will invariably emerge over time. In order for consent to be informed, individuals need to understand that there may be risks that are currently unknown, and they do not, and will not, know all the ways in which the data may be used.4

Some primers on ethical data sharing recommend that broad consent for unspecified future use should be routinely obtained from participants.5,6 It is recommended that researchers avoid promising that data will not be shared; with more journals requiring data sharing for the purposes of reproducibility, this may hinder publication. Moreover, researchers should not promise that future analyses will be constrained to certain topics, as this limits the usability of data. However, broad consent for unspecified future use brings with it additional ethical considerations. Under TCPS-2, researchers must consider that, if broad consent for data sharing is a condition of participation, then there is a risk of coercion to share data, particularly if the study holds benefits for participants (e.g., clinical trials).7 Moreover, individuals should not be excluded from participation only because they do not wish to share their data. Therefore, it is recommended that Canadian researchers separate consent for data sharing from consent for study participation. As such, consent templates that are developed outside of the Canadian context that have open data sharing as a mandatory condition of study participation, such as the Open Brain Consent Template,8 are no longer aligned with TCPS-2.2

The need to obtain separate consent for unspecified future use is somewhat at odds with open science best practices. One concern the BARE Open Science Committee raised with Canada’s Panel on Research Ethics is that if some participants decline to provide broad consent, then the published findings will not be reproducible from the partial dataset that is permitted to be shared with the scientific community (the Request for Interpretation submitted to the panel is available at https://osf.io/zg249/files/). Given many journals require data to be shared, some researchers may exclude from analysis the data of participants who did not consent to data sharing, so that the published study results align with the shareable portion of the collected data. Clearly this practice has negative ethical implications, including the lack of transparency, irresponsible use of participant time, and wasting research funds to collect data that will not be used. The Panel clarified that broad consent is not required to share data with a journal for verification in the context of peer review, such as error detection and reproducibility.7 However, it is often the wider scientific community who undertakes these forms of verification (e.g., see9 for examples of reproducibility projects) and the open sharing of complete datasets facilitate these reproducibility efforts.10 The Panel did concede that researchers can make a case to their REB for data sharing to be a condition of participation, such as when the study objective is to create a large shared dataset (e.g., Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration and Aging, CCNA11), but that mandatory data sharing should be an exception.

Another related concern is that explicitly asking participants for consent to share data may encourage participants to opt out of data sharing, further compounding this issue. In contrast to this perception, however, a number of studies have found that participants are generally in favor of sharing both research data12,13 and routinely-collected health data14,15 for the benefits of advancing scientific knowledge and helping others. Although it has been stated that most patients want their data made available in order to accelerate the development of treatments and cures,16 and opt-in rates have been estimated at 90% for neuroscience studies,17 we are not aware of any studies reporting data on the rates at which participants actually opt-in to data sharing in neuroscience research.

Balancing Data Sharing with Participant Confidentiality in Neuroscience Research

Open data sharing is built on the FAIR principles – that shared data be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable.18 Accessibility is often interpreted as public accessibility, but this may not always be appropriate. Protecting participant confidentiality and privacy is central to ethical data sharing and becomes paramount when data are sensitive and its disclosure may harm participants.19 Jwa and Poldrack20 argue that neuroscience data – which includes medical information including diagnoses of neuropsychiatric conditions, measures of cognitive functioning (e.g., on neuropsychological tests or experimental cognitive tasks) and various modalities of brain imaging (e.g., electroencephalography [EEG], magnetoencephalography [MEG], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], positron emission tomography [PET]) to measure brain structure and function – are particularly sensitive.8 For instance MRI images can be inherently identifying, capturing the physical form of the face and skull, hence skull-stripping being a best practice for de-identifying data.21 Even so, unique gyral folding patterns captured by structural MRI images can enable the matching of participants across MRI datasets, and could potentially be used for re-identification with developments in artificial intelligence.22 Brain images not only reveal existing health conditions and estimated brain age,23 they can also be used to estimate the risk of future neurological and psychiatric conditions. For instance, a single MRI at age 45 can be used to predict future physical frailty, chronic diseases and mortality.24 Moreover, images capture brain abnormalities with high specificity that, if rare in type and location, could be potentially identifying (e.g., an abnormality in a circumscribed brain region).

Jwa and Poldrack20 raise the issue that unlike other medical data, neuroscientific data is particularly intimate – being central to one’s identity and personhood – and the potential for decoding one’s thoughts, mental states, or personality characteristics from patterns of functional activity could be a violation of mental privacy. They note that the risks of decoding may be more conceptual rather than actual, at least for the time being, however their discussion highlights important considerations for neuroscientists planning to share imaging data. For instance, functional MRI (fMRI) studies of autobiographical memory involve participants recalling past personal experiences both inside and outside of the scanner.25 Transcripts of autobiographical memories must be rigorously de-identified before they can be shared or data use agreements must be in place.26 Presumably the same protections should be applied to the fMRI correlates of these memories if future decoding technologies could render these neural patterns as memory “transcripts”.

Some of these issues highlight the need for researchers to approach data sharing with intentionality and responsibility. It is important to consider that within a single study, different methods may be appropriate for sharing different data types, depending on the sensitivity of the data and potential for re-identifiability. This granular approach can also be applied to consent, such that participants are given the opportunity to decide which types of data they are willing to share.20

Open Science and Data Sharing at BARE

BARE is situated on the campus of Baycrest, a geriatric hospital in Toronto, Canada, and is composed of the Rotman Research Institute (RRI) and the Center for Education. RRI is home to around 23 principal investigators conducting research on aging, cognitive neuroscience, and brain health. Researchers have access to multiple onsite neuroimaging methodologies (3T MRI, MEG and EEG), and several specialized centres including the Kimel Family Centre for Brain Health and Wellness,27 the Anne and Allan Bank Centre for Clinical Research Trials, and the Ben & Hilda Katz Interprofessional Research Program in Geriatric and Dementia Care. RRI also hosts multi-institute neuroscience initiatives such as the CCNA. The Centre for Education also conducts research projects, and Baycrest Hospital also has a number of clinical researchers. All research activities involving human participants at RRI and Baycrest Hospital must be reviewed and approved by the Baycrest REB.

Over the past 5 years, BARE has been developing an Open Science initiative with funding from the Tanenbaum Open Science Institute.28 A key component of this work has been developing a close partnership between the BARE Open Science Committee and the Baycrest REB to integrate open science considerations in REB processes. To date, activities have included: (1) adding dedicated sections on data sharing and future data use to the REB application form; (2) approving template consent language for data sharing that follows TCPS-2 guidelines (as described above); (3) adding a new question to the REB Annual Report to systematically track the number of participants consenting or declining to share their research data; and (4) reporting data sharing consent rates to the BARE Open Science Committee.

The Current Study

To the best of our knowledge, there has not been a systematic investigation of the number of neuroscience studies with plans for data sharing, and the rates at which participants consent to data sharing when it is optional (i.e., not a mandatory part of study participation). The aims of this research are twofold: (1) to report statistics on data sharing plans and consent rates at a Canadian neuroscience institute; and (2) investigate the factors that influence whether researchers plan to share data and whether, if given the option to choose, participants consent to share their data for unspecified future use. Importantly, this study will establish a benchmark for open science consent practices in Canadian neuroscience research institutes, and provide data to inform decisions made by researchers and REB about sharing data for unspecified future uses.

In this quantitative documentary analysis, we reviewed the files of all currently active projects lodged with the Baycrest REB, examining the content of data sharing plans and consent forms. Documents from healthcare institutions are a rich source of written data on how organizations organize and implement services29 – in this case, open science practices within research conducted under the oversight of the Baycrest REB. We systematically coded a number of variables including the study population, types of data to be shared, whether data sharing was optional, and if so the rates at which participants opted out of data sharing.

We hypothesized that plans for data sharing would be less likely for highly identifiable data (e.g., audio or video data), more sensitive data (e.g., neuropsychological test data, biological samples) and studies involving vulnerable populations (e.g., patients with neuropsychiatric or other health conditions). We also explored whether data sharing plans varied by study design and whether or not testing involved an in-person component. We expected that data sharing plans would be more likely in newer studies given the increasing awareness and uptake of open science practices,30 and that for those studies planning to share data, that the provision of optional consent would be more common since the change in TCPS-2 in 2023. We also predicted that data sharing would be most common in studies being run at the RRI; working primarily in the fields of neuroscience and psychology, these researchers likely have more knowledge of open science than those based in other parts of Baycrest (e.g., Centre for Education, Baycrest Hospital). Finally, in line with previous studies indicating high participant support of data sharing reviewed above, we expected rates of consent for data sharing to be high; we did not have a clear hypothesis as to whether consent rates would vary according to study population.

Methods

The current study was not pre-registered. REB approval was not required. Data and analysis code are available on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/zg249/).

Sample

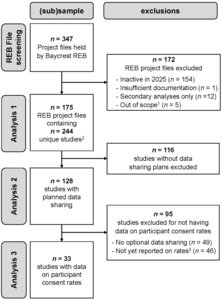

Figure 1 provides a flow chart of the REB project files and studies included or excluded from each analysis in this quantitative documentary analysis. Screening of the 347 research project files held by the Baycrest REB resulted in the exclusion of 172 files for reasons such as being inactive in 2025, not having sufficient documentation to code for the variables of interest (i.e., REB application form, study protocol, and approved consent forms), involving only secondary analyses of existing data (i.e., no collection of primary data from participants), or being out of scope (e.g., projects assessing general participant eligibility for subsequent studies, or program evaluation). The final sample comprised 175 REB files; 19% of these projects included multiple studies, for a total of 244 studies that were examined for their data sharing plans. As shown in Figure 1, studies were further filtered for analyses on provision of optional consent and participant consent rates. For studies providing optional consent for data sharing, we extracted from annual reports (if available in the REB file) the reported rates at which participants agreed to share their data. Note that these data were only available for 42% of the studies using optional consent for two main reasons: (1) reporting optional consent rates is a new section in the Baycrest REB annual report and over a third of studies sharing data started in 2024-2025 and had not yet submitted an annual report; and (2) some studies submitting an annual report had no data to report (e.g., recruitment had not started).

Data extraction and coding

The documentary analysis involved the extraction of data and coding of 15 variables shown in Table 1. One researcher (D.G.) coded all REB files. First, a subset of 5 REB files were coded and discussed with two senior researchers (D.R.A. and N.D.K.) to ensure consensus. Any queries about coding subsequent REB files were resolved by consensus (D.G. and N.D.K.).

We used the year of the initial REB application as an estimate of when the study was started. We grouped the year data in two ways: firstly into four 5-year bins, and secondly into those that started prior to 2023 and those that started on or after January 1, 2023. This latter distinction was made for two reasons: in 2023, the new TCPS-2 requirement for a separate consent option when obtaining broad consent for unspecified future use of data came into effect, and the Baycrest REB introduced template consent language for open science data sharing31 as part of our open science initiative at BARE.

Study population was coded according to the perceived vulnerability of the participants within the study context. We categorized any study that recruited participants under the age of 18 years (whether participants had a health condition or not) as ‘youth’, even if the study involved adults. Any study enrolling adult participants with a health condition were categorized as ‘patient’; in the majority of these studies, the health conditions related to memory impairment (including subjective cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, amnesia) or another neurological or psychiatric condition; some studies focused on geriatric conditions such as hip fractures or pressure injuries; and a few studies included health conditions with implications for neurocognitive function such as bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). Studies enrolling healthy adults of any age over 18 years were categorized as ‘healthy’, unless these participants were tested in their work capacity (e.g., health care professionals, carers) in which case they were classified as ‘worker’. Although we had planned to examine studies on healthy older adults separately from studies testing only healthy younger or middle-aged adults, a non-trivial portion of studies only stated that they were planning to recruit healthy adults aged 18 years or over without specifying if this group included older adults.

We coded the data type(s) collected in a study. ‘Alphanumeric’ data is a very broad category that includes, for instance, performance metrics on experimental tasks, survey responses, and all kinds of derived data (e.g., fMRI signal, coordinates, volume of brain regions). ‘Neuropsychological’ data was coded separately from alphanumeric data given these include pencil and paper records of performance and are considered more sensitive in that these are clinical tests. ‘Audiovisual’ data were audio- and video-recordings as well as photographs of participants. ‘Transcripts’ were narrative data, and although usually derived from audiovisual data they were coded separately because direct identifiers (face, voice, etc.) were no longer present. However, these data were not collapsed with alphanumeric data given the often sensitive content of transcripts, reflecting conversations and interviews with researchers. Note that a concentration on memory research at BARE means that many of these transcripts describe autobiographical memories of personal experiences. ‘Biological samples’ included blood, cerebrospinal fluid, saliva and urine samples. ‘Brain imaging’ methodologies were EEG, MEG, structural and functional MRI and PET. ‘Other’ data types eye-tracking and DEXA scans to assess bone strength.

The level of data identifiability referred to whether data were de-identified (i.e., coded with a participant number), anonymized (i.e., the key linking participant codes with identity is destroyed), anonymous (i.e., no identifiers were ever recorded, such as in online studies); or identifiable (i.e., some identifiers remain to, for instance, provide linkages across national datasets).

Documents were examined to determine whether any of the data types collected were going to be shared. For studies planning to share data, we then examined the consent form to determine whether a template was used for the section on data sharing, and whether participants were provided with information about open science to give the broader context in which data sharing was to occur. Information about open science included statements that data sharing would allow other researchers in the scientific community to conduct future research studies on the topic or to explore additional or new research ideas, as well as statements about the general aims of open science such as advancing scientific progress, building knowledge and improving health; increasing transparency and reproducibility; enabling replications; and to encourage collaborations. It was determined whether the intended audience for the shared data was internal or external to the institution. We coded whether a data repository was mentioned, and if so, whether a definite repository was named or examples of repositories being considered were provided. We coded whether data sharing for unspecified future use was optional or a mandatory condition of study participation, and for studies where it was optional, whether the consent question was posed as an opt-in, opt-out, or yes/no decision. Finally, we coded whether data on optional consent rates were available, and if so, these data were extracted for further analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were computed in R (version 4.4.3).32 Although the data have a nested structure, most PIs and most REB projects were only associated with a single study, and thus mixed effects models specifying either PI or REB project as a random effect failed to converge. Therefore the reported models include only fixed effects. Multivariate logistic regressions were computed using the glm() function. To determine the factors that predicted the likelihood of whether or not a study planned to share data for unspecified future use, the regression model had 11 predictors (see Table 2) including separate predictors for each data type (because a single study could have multiple data types). To examine the factors predicting the likelihood of participants consenting to share their data, we ran another logistic regression with three predictors. For each multivariate logistic regression, the significance of each predictor was assessed using a type-III ANOVA as implemented in the Anova() in the R package ‘car’ (version 3.1-2).33 For any significant predictors, we compared the levels of that factor to a reference level while controlling for all other predictors in the model using the R package ‘emmeans’ (version 1.10.4).34 Finally, for the analysis of whether provision of optional consent changed before and after 2023, a chi-squared test was computed. R packages ‘dplyr’ (version 1.1.4)35 and ‘tidyr’ (version 1.3.1)36 were used for data manipulation and ‘ggplot2’ (version 3.5.2)37 was used for visualization.

Results

Descriptive statistics

An overview of the studies included in the documentary analysis is provided in Table 1. Unsurprisingly, two-thirds of the studies are part of research projects being conducted at the RRI, and given only active studies were considered, two-thirds of these projects were started in the past 5 years. The majority of studies (75%) had observational as opposed to interventional (25%) designs, and 72% of studies had an in-person component. Almost half of studies (44%) enrolled adult participants with health conditions (i.e., patient populations) and another 40% tested healthy adults; very few studies tested youth (4%) or workers (12%).

Alphanumeric data was the most common type of data, collected by 93% of studies. In line with the neuroscience focus of BARE, 35% of studies included some form of brain imaging (e.g., EEG, MEG, MRI, fMRI, PET) and another 41% collected neuropsychological test data. Less frequent data types were audiovisual (20%), biological samples (10%), transcripts (15%) and other (7%). The majority of studies (90%) used de-identification to protect confidentiality, which is unsurprising given that the in-person nature of most neuroscience studies (e.g., neuroimaging, neuropsychological tests) do not allow for anonymous data collection, and anonymization is prohibitive to longitudinal tracking of participants with health conditions.

Approximately one-half (52%, n=128) of the 244 studies planned to share data for unspecified future uses; of the 91 studies launched since 2023, over 60% have data sharing plans. Our examination of the consent forms in these 128 studies indicated that only 23% used a template consent form designed to explain data sharing to participants, and 56% of studies framed data sharing in the broader context of open science. In almost all cases (97%), data were intended to be shared with an audience external to the institution. Although 55% of the studies planning to share data mentioned a repository in the consent form, mostly this was the provision of example repositories that might be used. By and large, Open Science Framework (OSF) was the most frequently named repository (n=31 of 47 repository mentions); this was followed by internal infrastructure (n=5), Canadian repositories for neuroscience data (e.g., Brain-CODE, n=4; CCNA, n=3), University of Toronto’s Scholars Portal Dataverse (n=2), and OpenNeuro (n=2).

We found that 62% of these studies (i.e., 79/128) separated consent for data sharing from consent for participation; that is, data sharing was optional rather than mandatory. This percentage was 80% for studies launched since 2023 (i.e., 44/55). Most commonly across the 79 studies, this consent decision was posed as a yes/no question (57%), with other studies using opt-out (25%) or opt-in (18%) formats.

What types of studies are more likely to share data?

We examined a number of factors that could potentially influence the probability that studies planned to share data for unspecified future use; full results are shown in Table 2. The overall model with all factors was significant (p < .001). First, the 5-year time window during which the study was started, as indexed by the year of the REB application, had a significant effect on data sharing plans (p < .001; see Figure 2A). Relative to studies launched between 2002 and 2007, data sharing was more common in studies started after 2014. Specifically, the predicted probability of data sharing for studies started in 2014–2019 (0.47) was 3.32 times more likely than those started in 2002–2007 (0.14). Similarly, the probability of data sharing for studies started in 2020–2025 (0.52) was 3.72 times more likely than for those started in 2002–2007 (0.14). There was a strong effect of the institution on data sharing rates (p < .001). Relative to studies run at the RRI where the predicted probability of data sharing was 0.60, data sharing was 2.84 times less likely in studies being run at Baycrest hospital (0.21), 4.30 times less likely in Clinical Trials Unit studies (0.14), and 2.21 times less likely in External studies (0.27). We found that the likelihood of data sharing did not differ according to whether the study design was interventional or observational (p = .464). Moreover, the inclusion of an in-person component did not significantly affect data sharing (p = .915). The predicted probability of data sharing was 3.15 more likely in studies collecting biological (0.49), than those without (0.15, p = .019); the collection of other data types did not have significant effects on data sharing plans (p values > .277; see Figure 2C).

In contrast to our hypotheses, the effect of population was not significant (p = .426; see Figure 2D). We reasoned that this null result may reflect population being confounded with institution, for example, that studies at hospitals are more likely to involve patients. A cross-tabulation showed that whereas the majority of studies at Baycrest Hospital (53%) and the Clinical Trials Unit (89%) involved patients, the majority of RRI studies (55%) involved healthy participants, and 100% of studies in Education involved workers. When Institution was removed from the regression, the overall model remained significant (χ2(14) = 30.18, p = .007) and a significant effect of study population on data sharing emerged (χ2(3) = 9.67, p = .022). Relative to studies on healthy adults where the predicted probability of data sharing was 0.57 (95% CI [0.35, 0.77]), data sharing was 1.49 times less likely for patient studies (OR = 0.47, predicted probability = 0.38, 95% CI [0.21, 0.60], p = .020) and 1.91 times less likely for studies on workers (OR = 0.32, predicted probability = 0.30, 95% CI [0.12, 0.58], p = .017). The estimated probability of planned data sharing in studies on youth was the lowest at 0.24 (95% CI [0.05, 0.66]) but this difference from healthy adults did not reach significance (OR = 0.24, p = 0.107). Nevertheless, these results should be interpreted with some caution given that the effect of Population was not significant over and above Institution in the full model, suggesting that the institution at which a study is conducted is more important in determining data sharing than the participant populations involved in the study.

Has the provision of optional consent changed over time?

Of the 128 studies planning to share data for unspecified future uses, 62% provided optional consent. Here we were interested in whether the year of study application might influence the probability of whether consent for data sharing was optional or a mandatory condition of participation. When examining the effect of the year the study application was made, we only report results for the pre- vs post-2023 comparison rather than by the five-year periods. This was due to the relatively low number of studies sharing data in earlier time periods (resulting in one cell with n=0 when broken down by optional consent). This analysis showed a significant effect of time, χ2(1) = 12.32, p < .001. Prior to 2023, just over half (52%) of studies had mandatory data sharing (38 of 73) whereas after 2023, this pattern reversed entirely with 80% of studies providing optional consent (44 of 55 studies).

What factors influence rates of participants agreeing to share their data?

We had data on consent rates available from 33 studies, representing consent decisions collected from a total of 2912 participants. Overall, 98.35% of these participants agreed to share their data for unspecified future use (95% binomial confidence interval: [97.82%, 98.78%]); only n=48 declined. Across studies, the mean consent rate was 98.03%, ranging from 90%-100% of participants opting in.

A multivariate logistic regression model examining the factors that might influence consent rates was not significant (p = .055; see Table 3 for full results), with none of the factors we examined having a significant effect on the rates of consent. That is, whether the studies began before or after 2023 (p = .061), included patients or only healthy adults (p = .324), mentioned data repositories in the consent form or not (p = .693), and irrespective of the format of the consent decision (opt-in, opt-out, or yes/no; p = .097), mean consent rates were approximately 98%.

Because this overall consent rate was based on the minority of studies for which consent rates were available, we tested whether studies with available consent rates differed systematically from those without to rule out any potential biases. Across a series of bivariate chi-square tests, we found no significant relationship between consent rate availability and any predictor of consent rates reported in Table 3 (p values ≥ 0.13). Moreover, annual reporting of consent rates to the REB is mandatory when data sharing consent is optional, and thus studies with low consent rates could not simply decline to report theirs. Thus, we have no reason to believe that the high average consent rate we found is not also representative of studies for which consent rates were not available.

Discussion

Trends in plans for open data sharing

A very clear effect in the current data was the increase over time in both the number of studies planning to share their data and describing this in consent forms, as well as studies making consent for data sharing an optional part of participation. In fact, we found that studies initiated in the last decade were more than three times as likely to share data that studies prior to 2007; of studies starting between 2023 and 2025, 60% were planning to share data, with 80% of these providing optional consent. Against the backdrop of broader shifts in open science culture, the increased use of optional consent also coincides with both the updated recommendations in TCPS-2 to use a separate consent decision for data sharing when future use is unspecified, as well as the Baycrest REB’s introduction of template consent language that includes an opt-out decision for data sharing. Although the BARE Open Science Committee deliberated over whether to use an opt-in or opt-out decision in the template consent, the findings presented here indicate that the format has little impact on consent rates – although it should be noted that some studies on data sharing do report a participant preference for opt-in decisions.38

One implication of the current findings is that the majority of studies employing an optional consent format are not able to share 100% of the study data, thus impacting the ability for the data to be used for replicability and reproducibility. In addition to missing participants, shared datasets can be incomplete because certain variables or data points are removed or “blurred” in order to preserve confidentiality. Common practices include transforming quantitative variables such as age to age bands,5 or for qualitative data such as transcripts, redacting or replacing potentially identifying information with more general placeholder terms.39 However, ensuring data quality is only one purpose of sharing data – and many aspects of data quality can feasibly be determined from a near-complete dataset. If, on the other hand, the purpose of data sharing is framed as promoting the re-use of existing data, then sharing a partial dataset achieves this objective.

As we had predicted, the identifiability of data influenced the likelihood it would be shared. However, although we had expected that some forms of more sensitive data, such as audiovisual data or neuropsychological test results, might be less likely to be shared, this was not the case. Instead we found that studies collecting biological samples were more likely to be planning to share data. This finding stands in contrast to research indicating that researchers can be hesitant to share biological samples, citing concerns of potential “misuse” of data as well as the finite nature of these specimens.40 However, the purpose of some studies, such as CCNA, is to deeply phenotype large samples of individuals, collecting multiple biological specimens (blood, saliva, urine and cerebrospinal fluid) along with neuroimaging and neuropsychological tests, in order to identify biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases – with the intention that these studies are made open to other researchers. In CCNA, data sharing is managed by committee to allay concerns of misuse and allocate finite specimens.41 Indeed, it was evident that many consent forms in our analysis outlined different methods of data-sharing for different data types according to sensitivity and risk of re-identification, in line with the adage, “as open as possible, as closed as necessary”.42 For instance, alphanumeric data might be shared on a public repository, brain images on request, and biological samples and audio recordings with a data use agreement. Future analyses should quantify how data-sharing methods vary with data types and whether these choices influence consent rates.

To increase shared understanding of ethical and regulatory conditions of data access and re-use for different types of data, researchers should be encouraged to make use of new developments such as the Data Use Ontology (DUO).43 This initiative has created a standardized vocabulary of data use terms that can be used to annotate shared datasets with permitted uses (e.g., “general research use”, “disease specific research”) and any conditions or restrictions (e.g., “ethics approval required”, “geographical restriction”, “non-commercial use only”, etc.) Importantly, the DUO annotations are machine readable, enabling researchers to more easily search for and find datasets with data use conditions that match their intended research uses.

Open Science Framework was the most commonly named repository in consent forms, consistent with the predominance of alphanumeric data to be shared. It is striking that of the 47 studies planning to share neuroimaging data, OpenNeuro was only mentioned in the consent forms of 2 studies, despite being a well-used repository.44 OpenNeuro requires that all uploaded data are made publicly available (under a Creative Commons CC0 license), making it impossible to keep shared data “as closed as possible” when this is required. Instead, Baycrest researchers planned to share neuroimaging data on Canadian repositories (e.g., Brain-CODE45 or CCNA46) or retain it on internal infrastructure for future sharing – all of which provide options for different levels of openness. Importantly, data does not have to be public to be accessible; even sharing only metadata can satisfy FAIR18 requirements as the data will be findable47 and should outline clearly how to access the data.42 Interestingly, with the increase focus on neurorights and the risks of re-identification from neuroimaging data, OpenNeuro recently announced they will be establishing tiered levels of access to facilitate the sharing of more sensitive datasets.48

Participant consent and open sharing of neuroscience data

This is, to our knowledge, the first study to report rates of consent for data sharing in neuroscience studies. We found that over 98% of 2912 research participants consented to sharing their data, and none of the factors we examined – such as the study population, format of consent decision, or whether a repository was mentioned – significantly influenced this rate. Moreover, rates of consent were stable over time, at least before and after 2023. The high rate of consent across studies at Baycrest substantiates previous reports that participants are in favor of data sharing,12–15 motivated for example by advances in the understanding of neuropsychiatric disorders and accelerating the development of treatments. Indeed, Meyer6 argues that these attitudes towards data sharing reflect the reasons why most participants volunteer to participate in research in the first place, and are congruent with participants’ expectations that reasonable efforts are made to ensure high quality research.

The findings reported here could be useful for ethics approval boards with respect to granting retrospective approval for data sharing where consent was not originally obtained from participants. Often it is impracticable to re-contact participants to obtain consent, and ethics boards have to determine whether it is likely that participants would have agreed given the information in the consent form. Relevant to this adjudication, our data show that consent rates have not changed appreciably over time, and do not differ between studies involving individuals with health conditions (including neuropsychiatric disorders) and those testing only healthy individuals. These retrospective decisions are complex and in addition to questions about data sensitivity and risk of re-identification, they are highly contingent on whether the original consent form was silent on data sharing or whether individuals consented to participate with the guarantee that their data would not be shared.6

The high level of participant support for data sharing contrasts somewhat to the data sharing plans of researchers. On the basis of the current data we cannot know the reasons why researchers might be more or less inclined to share data, although we did find that studies conducted in a hospital or clinical trials setting were less likely to be sharing data. It has been suggested in the literature that a hesitancies to engage in open data sharing can arise when working with vulnerable populations, perhaps because of uncertainties around regulations that govern data sharing,49 concerns that potential harms related to data sharing may be heightened by their vulnerability,13 or as Wallace et al.50 suggests, a “misplaced commitment” to protect the privacy of participants. The authors recommend that researchers increase their understanding of the ethics of data sharing and suggest that REBs have a role to play in educating researchers.50 At Baycrest, the REB and Open Science Committee have co-run several workshops on ethical issues in open science including data sharing, and the REB runs a “Chat with the Chair” session a few times a year to facilitate informal discussions around ethical issues.

Another interpretation, however, is that many participants, healthy or otherwise, do not fully understand what ‘data sharing’ means or the potential implications of sharing their research data. Some research has shown that the understanding of consent forms is far from complete51,52 and finding ways to improve participant comprehension is imperative. Encouragingly, research has shown that the use of enhanced consent forms – well-designed brochures using language at the 8th grade reading level – significantly increases participant understanding, as do extended conversations that facilitate trust-building and allow opportunities for questions.53 These concerns notwithstanding, a large study by Mello et al.13 found that participants in clinical trials are aware of the potential risks of data sharing, including that their data could be stolen or used for commercial purposes, yet 82% of them judged the perceived benefits of sharing their research data to outweigh these risks.

Limitations of this research

This work is not without its limitations. This is a single-institution case study of open data sharing practices and consent rates at a small Canadian research institute with a specific focus on geriatrics and cognitive neuroscience. Although these characteristics limit the generalizability of these findings to other institutions, countries and research specializations, we hope that the deep analysis and recommendations presented here will support and inspire increased uptake of open data sharing practices in the neurosciences.

We were not able to directly compare consent rates between different populations because currently, researchers only report to the REB consent numbers at the study-level. As such, we were only able to compare studies that exclusively enrolled healthy individuals with studies that involved at least some participants from potentially vulnerable populations. Additionally, we were not able to separate studies recruiting healthy older adults to determine whether data sharing practices differed for older versus younger adults for several reasons. For the majority of studies, the REB application indicated they were recruiting healthy “adults” aged 18+ years without specifying an upper age limit, making it impossible to identify which of these studies recruited older adults. Of those REB files that did indicate involvement of older adults, almost three-quarters involved another, arguably more vulnerable, group such as patients. In future, we hope to collect more granular data to help us better assess these questions.

A further limitation is that the study sample excludes REB files that were inactive in 2025. Consequently, data from earlier time periods (e.g., 2002-2007) likely skew towards long-running studies, rather than a full representation of ongoing research during that time period. Thus, it is possible that survivorship bias may have influenced the baseline and temporal comparisons analyzed in this report.

Another limitation is that we are only able to examine the numbers of participants opting in (or out) of data sharing when it is optional. That is, the number of participants in studies with mandatory data sharing who would have opted out of data sharing if given the choice can never be quantified. Further, we did not have data on the numbers declining to participate in studies because they do not wish to partake in mandatory data sharing, and acquiring these data was beyond the scope of the current documentary analysis. However, our results here suggest that the rates are likely low. It was also beyond the scope of the current study to track whether studies planning to share data eventually did so; this will be a goal for future research.

Recommendations

On the basis of our findings, we make several recommendations that we encourage other neuroscience institutes in the Canadian neuroscience eco-system (and beyond) to consider adopting. First, institutes would benefit greatly by encouraging better collaboration between open science teams and REBs. Given that data sharing can be practiced in ethical and responsible ways, obtaining REB approval should not be the major impediment for open science. A strong collaboration can underpin the successful implementation of our other recommendations. First, there is value in having data to inform policy and to identify gaps in practice, and so we recommend that other neuroscience institutes adopt similar practices in systematically tracking consent rates and related metrics. One possibility is that consent codes – annotations originally developed to track the re-use restrictions from consent forms54 – could be repurposed and expanded to enable open science teams to easily compute statistics such as those we have presented here.

Second, open science teams and REBs should work collaboratively to produce clear guidelines for responsible sharing of different data types (perhaps has part of an institutional resources for creating data management plans), as well as template consent language for data sharing that are aligned with relevant ethical regulations (e.g., TCPS-2). Templates can be developed for the sharing of data types commonly collected at the institute, for different methods of data sharing, or tailored to the needs of populations commonly involved in local research. For instance, the University of Ottawa Heart Institute has created template consent language for public as well as controlled data sharing.55 Third, it is important to educate researchers about responsible data sharing so they are well-equipped to provide simple explanations to research participants and answer their questions during the consent process. Ideally, educational activities should target all researchers, from the principal investigators developing and overseeing the projects to the research assistants and students who are often the point of contact with participants. Our results also indicate that researchers who are based outside of research institutes and universities – such as hospital clinicians – need more exposure to open science principles and practices. At Baycrest, we are confident that all of the above efforts will see a continuation of the upward trajectory in the number of studies planning to share data.

Conclusions

In summary, this study provides a benchmark for open data sharing in Canadian neuroscience institutes. Recent years have seen a significant increase in open data sharing at BARE, with 60% of studies launched since 2023 planning to share data and 80% of these studies providing optional consent. We found that over 98% of 2912 participants in Baycrest studies agreed to their research data being shared for unspecified future use, and this rate was unaffected by the participant population or the format of the decision. We found that studies collecting biological samples were more likely to have planned for data sharing, and noted some trends regarding repository selection for neuroimaging data. Given the importance for data sharing in neuroscience, we provide recommendations that we hope will assist other Canadian neuroscience institutions in increasing data sharing practices among their researchers. Our experience at BARE has shown that a strong collaboration between the open science team and the REB is foundational to this endeavor. It has yielded a comprehensive understanding of the open data practices at our institute that we report here, and it is enabling us to identify and actively address the educational needs of our researchers as we support them in sharing neuroscience data openly, ethically, and responsibly.

Author Contributions

DRA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization, Supervision, Funding Acquisition; DG: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing, Visualization; NDK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision; IK: Formal Analysis, Writing – Review and Editing, Visualization; MA: Writing – Review and Editing, Visualization

Data and Code Availability

Data and analysis code are available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/zg249/).

Funding Sources

DRA and DG are supported by the Canada 150 Research Chairs program. MA is supported by a Tanenbaum Open Science Institute grant. IK is supported by a Data Sciences Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship from the University of Toronto.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Daphne Maurer, the Chair of the Baycrest REB, and the BARE Open Science Committee for helpful discussions.

_probabilities_that_studies_planned_to_share_data_for_unspecified_future_use_broken_dow.png)

_probabilities_that_studies_planned_to_share_data_for_unspecified_future_use_broken_dow.png)