Introduction

Acquiring physiological data during neuroimaging experiments is crucial for enhancing the quality and interpretability of neuroimaging data. Leveraging physiological signals allows the user to: 1) model and remove the effects of physiological fluctuations on neural fluctuations of interest in the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signal,1 2) interrogate the relationships between these physiological fluctuations and fluctuations of interest in the neural signal; and 3) monitor the state of the participant in real time.2,3 Inherently, the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) fMRI signal is based on the susceptibility contrast between oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin and can be used to measure cerebral oxygen changes, presumably coupled with neuronal activity.4–6 However, the BOLD fMRI signal is also impacted by physiological processes including respiration and heart rate.7–10 While an active field of research, there is still much to be done in distinguishing regional neurovascular coupling from global physiological processes and improving the understanding of the variance explained through physiological signals in fMRI data.11–15 As the field moves forward, the evaluation and development of models and processing techniques for reconciling changes in physiological states with changes observed in this BOLD contrast is ever-changing and constantly improving.16–18

Importantly, physiological variance in fMRI signals does not always represent a confound but can provide valuable information for understanding cerebrovascular health19,20 and characterizing complex brain-body interactions.19–22 Further, it has been well supported that not accounting for physiological fluctuations can reduce the validity of using contrasts such as BOLD fMRI as a direct surrogate for neural activity.23 Yet collection of good quality physiological data during a neuroimaging session, whether research or clinical, is still non-trivial.24 As a community, we must turn the knowledge from years of experience collecting such data into practical and accessible guidelines, encouraging both experienced and new users to become familiar with the latest recommendations for physiological data collection and analysis prior to initiating a new study. The Physiopy community has set out to generate a comprehensive resource of all matters related to physiological data. Physiopy is an international community of volunteers that meet monthly to a) discuss the development of our open-source analytical tools or b) host open discussions and build documentation around Community Practices for physiological data acquisition, preprocessing, and analysis, within the scope of neuroimaging studies[1]. The community was first created in 2019 to help address a gap in open-source tools for processing physiological data.

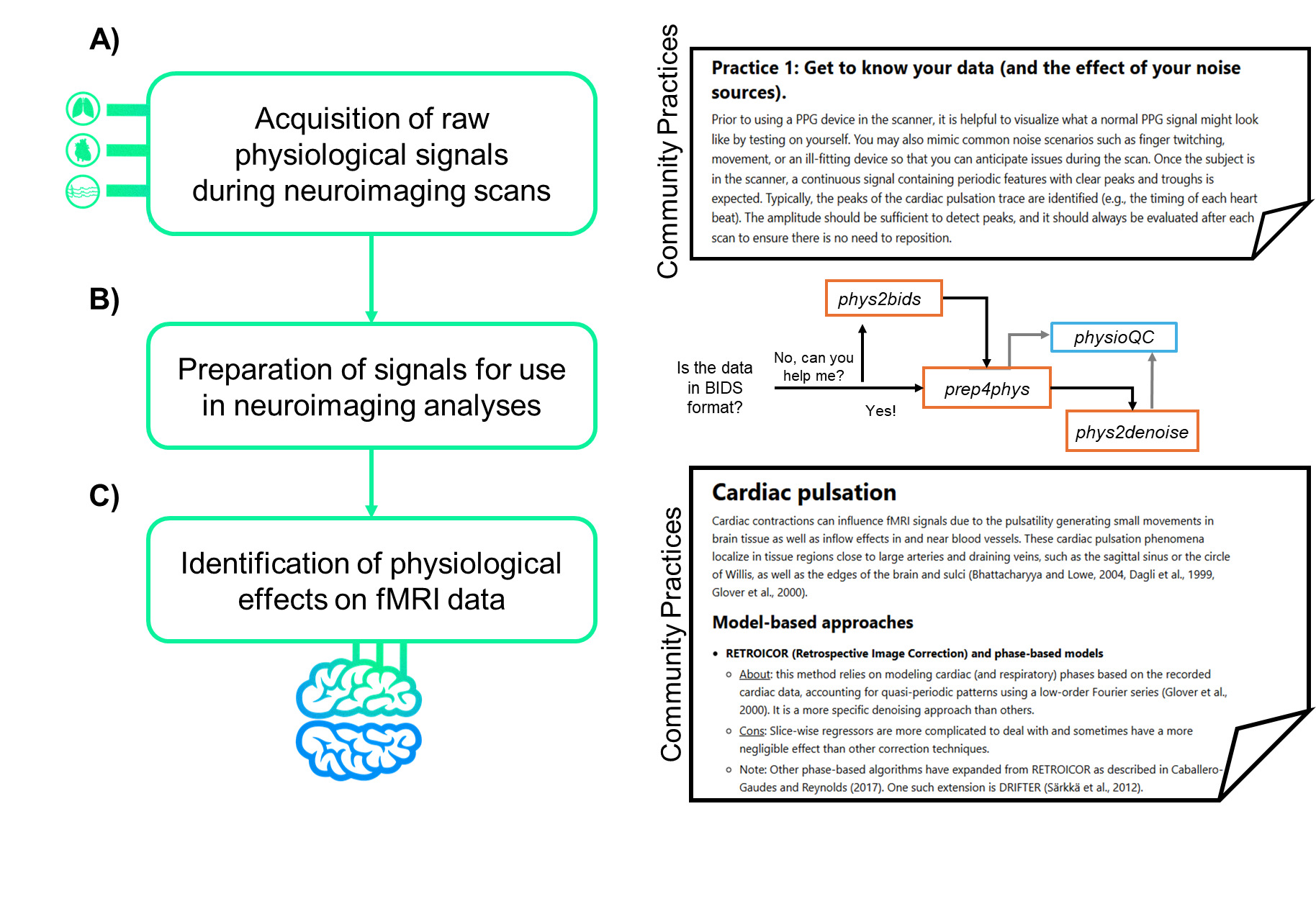

As a software package, Physiopy provides libraries to support every step in the process: 1) phys2bids25 segments raw physiological recordings into runs and organizes these files into the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) format26; 2) prep4phys (previously called peakdet)27 preprocesses and cleans physiological timeseries; 3) physioQC28 aims at assisting quality control and quality assessment of physiological data; and 4) phys2denoise29 provides methodology to extract key physiological metrics and regressors relevant to neuroimaging data to use in cleaning and analyses.

It was while building such tools that the community realized the need of a set of agreed common practices for their usage, so it started reaching out to international researchers, including many leading researchers in the field, to help guide its conversations, recommendations, and current practices for physiological data collection and analysis. The culmination of this volunteer-based work has resulted in a live resource that reflects the consensus of our community members and these discussions. This resource focuses on organizing and setting up physiological monitoring systems, common methods of acquisition and important practices to ensure high quality data, and various methods and guidelines related to the utilization of cardiac (photoplethysmography and electrocardiography) and respiratory (ventilation and gas concentration) data in the context of fMRI signals (see Figure 1). We believe that providing open access to this knowledge, promoting engagement, and building these guidelines are essential to the productivity and advancement of the neuroimaging field.

Building the Physiopy Community Practices

The documentation on community practices in physiological data acquisition is the result of a large voluntary effort by Physiopy members to bring structure to a vast physiological knowledge base and disseminate this information in the form of a live resource. The current version30 is the product of seven community wide discussions conducted semi-annually since 2022. The information that was compiled from these meetings reflects the consensus reached by our international community members, with an average of 11 members (range: 5-16 participants) in attendance at these discussions, with many of these members representing the wider perspectives of their respective research labs. The latest version of this resource can be found at https://physiopy-community-guidelines.rtfd.io.

Meeting Organization

During our regular monthly meetings, we curate a list of potential topics to discuss with the greater community and decide on one that is most relevant to the majority of our community for the next meeting. We ensure that our community discussion meetings are well attended by experts in the field through personal invitation or their standing interest and commitment to Physiopy’s success. We also encourage the presence of newcomers to ask questions and explore aspects of the discussed topics that may be overlooked by experts, ultimately making sure that the documentation serves well its main target. However, these discussions are open to participation from any experience level as that helps us build the most valuable and pertinent community practices for the broader community. We actively search for new contributors through word of mouth, advertising during brain hacks,31 talks, educational courses, conferences, and through dissemination of our website. We strongly encourage those interested in participating to reach out to the community mail contact[2].

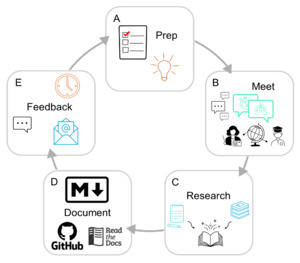

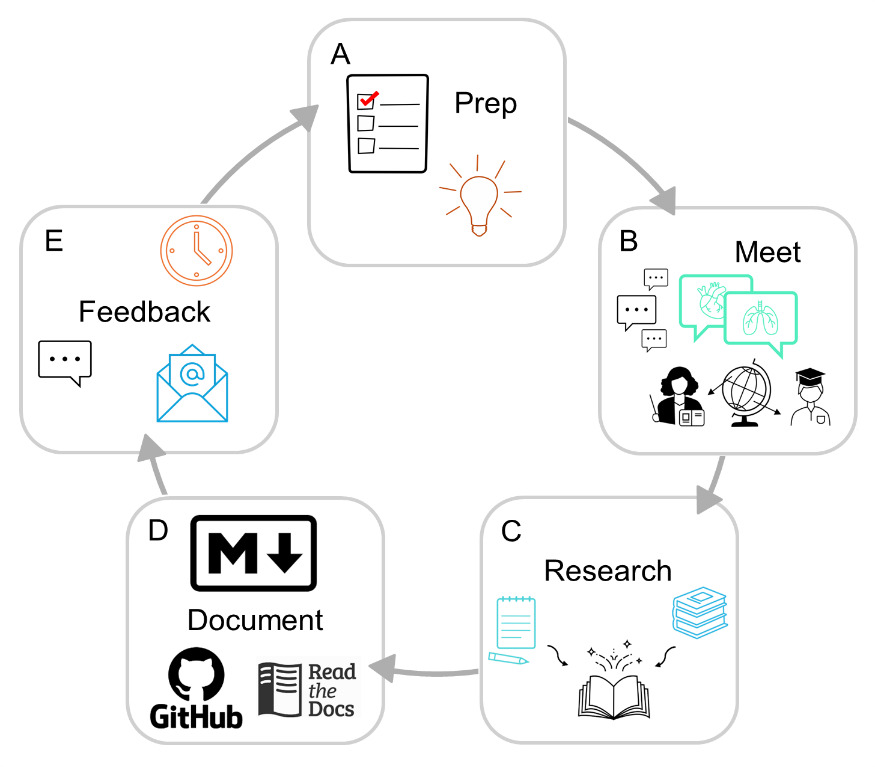

The discussion is moderated with a pre-compiled list of questions and discussion topics reviewed by other members of the team. The floor then opens for discussion and expands on the given prompts to provide recommendations, pros and cons of certain techniques and methods, and even personal accounts of previous attempts to improve known issues. We not only provide consensus on common points of confusion or technical limitations that arise during data collection and processing but also work to compile lists of ongoing questions or obstacles that would benefit from collaborative discussion and problem solving. These meetings are well documented by volunteer note-takers and are recorded via Zoom, with recordings stored for use internal to the community and accessible to others upon demand only to ensure that international privacy and data laws are abided. The consent and approval of all attendees across these meetings is obtained prior to our dissemination of the findings. All up-to-date meeting recordings and notes have been transcribed and compiled into our live resource[3] that will continue to be updated as future meetings take place to expand and improve our content. We ask all contributors in these meetings to review the documentation prior to its publication on the website. A flow chart for this process is shown in Figure 2.

Knowledge Dissemination

After compilation of the latest version of our practices by members of the Physiopy community into Markdown files hosted on a GitHub repository, we share a draft with all attendees of the community practices meetings for peer review and give them a month to provide feedback in the form of comments and clarifications, suggested additions or deletions, and approval. Once the feedback of all members has been incorporated, we finalize approval through a GitHub pull-request[4] to the documentation repository as well as through email feedback to make the process as accessible as possible for members of the community. Contributions to these resources are reflected on our live resource where we acknowledge and value contribution through writing the documentation itself, conducting research, answering questions for the community and members, reviewing pull requests or working on infrastructure, contributing ideas, planning, and giving and integrating feedback at any level.

Our community practices are released under the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 4.0 International license.30 The practices’ content is disseminated in a version-controlled format, leveraging Read the Docs for releasing and Zenodo for DOI indexing, with a mixed time-based and semantic version schema (year.major.minor release). This indexed version control approach allows us to continually make updates as the field evolves while guaranteeing provenance and accountability of all previously released recommendations and discussions, creating a documented timeline and facilitating ongoing open discussions on GitHub. We further encourage readers and users to submit discussion or content questions and concerns in the form of a Github Issue on the community practices website repository or reach out by email on an ongoing basis. The continued sustainability of our community practices resource will be upheld through our minimum viable governance structure[5]. The governance structure consists of a steering committee to guide and organize the operations of our community (community manager(s), development seat, and documentation seat) and an advisory board consisting of senior level researchers in the field that provides counsel for the steering committee and suggestions of the community’s activities. The workload amongst the remainder of the community is divided based on interest. Lastly, as mentioned above in “Meeting Organization”, we continuously seek newcomers to join our initiative and the steering committee has measures in place to ensure that active participation in the organization is accessible to newcomers and that they have access to the organization’s on-boarding materials.

As we continue to accumulate information at future meetings and through committee re-elections, the review process will remain the same. We consider our documentation to be a live resource and encourage readers to reference our website for the latest versions, while citing the consulted version of the documentation through its DOI.

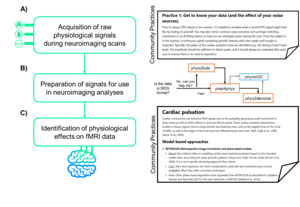

Overview of Physiopy Community Practices

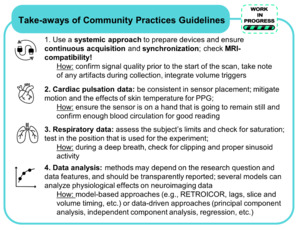

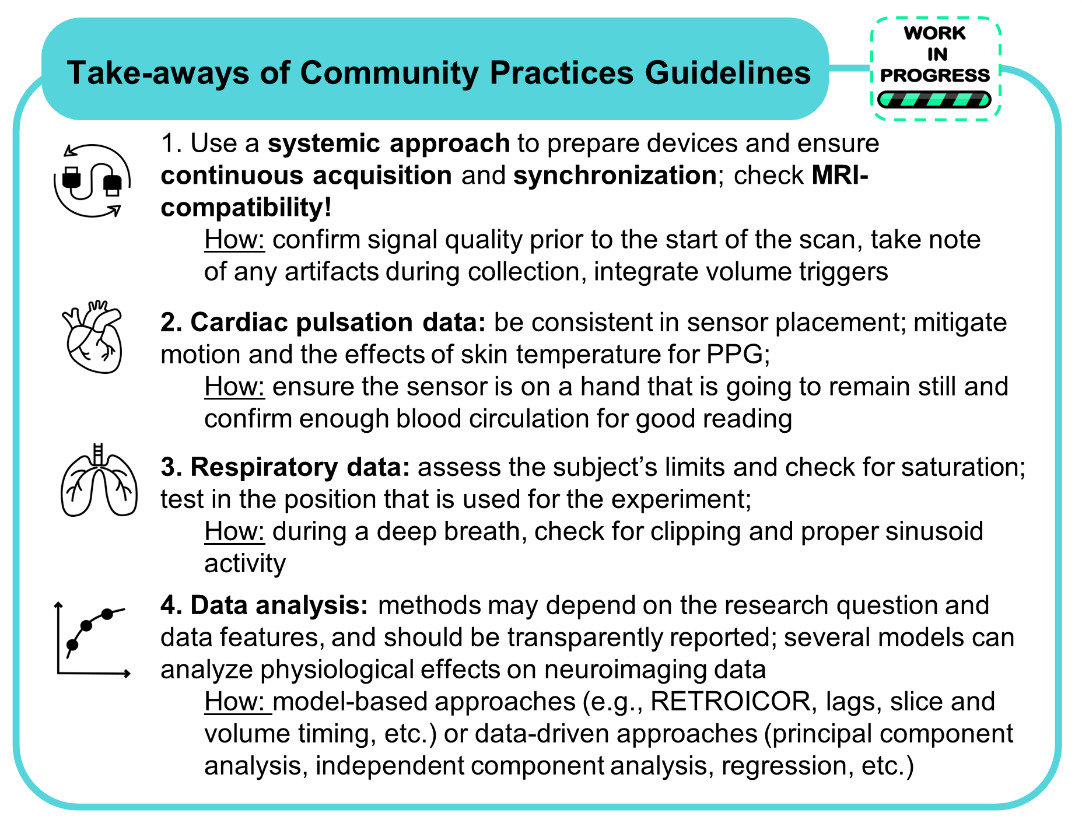

Within our current core community, the most common types of physiological data acquired are cardiac – either photoplethysmogram (PPG) and/or electrocardiogram (ECG), – and respiratory – either ventilation (respiratory belt) and/or gas concentration (particularly expired carbon dioxide, i.e. CO2). Typically, these are obtained simultaneously with fMRI data, which is the most widely used neuroimaging technique in our community. As of now, we have produced extensive documentation on the importance of acquiring physiological data during fMRI, methods for acquiring physiological data, and methods for using physiological signals to improve modeling of fMRI time series. In this section, we report summary concepts on each major section of our community practices (see Figure 3). We would like to emphasize that our practices and recommendations are toolbox agnostic, providing the key information needed behind the development or implementation of any open-source tool to inform the reader and promote shared consensus of good practice to a wider audience.

Importance of Physiological Data for Both Noise and Signals of Interest

Briefly, monitoring physiology during neuroimaging is critical to assist in characterizing the given subject’s physiological state and to track any variations that occur whether at rest or during specific tasks in the scan. Without these signals, it is difficult to model how physiological factors might manifest in the fMRI time series. Depending on the research question at hand, physiological fluctuations can be identified either as “noise” or “signals of interest”.

The most common use of physiological fluctuations is to isolate signal changes in the brain that are associated with the hemodynamic response to a neural stimulus.1 In this situation it is important to model and remove the signals with a remote, non-neural origin, such as breathing or cardiac related effects. On the other hand, characterizing the physiologic effect in fMRI experiments may be the goal. This is common for studies that rely on gas concentrations to map cerebrovascular reactivity and quantify factors like the dilation of blood vessels during non-neural stimuli.32–35 Furthermore, studies that are looking at arousal/vigilance or autonomic system features may require physiological signals to best parse the results.17,18,36–40 All-in-all we encourage all fMRI researchers to collect these data to more fully capture the variable human physiology inherent to imaging experiments to best interpret and evaluate the research question they are asking.

Acquiring Physiological Data

Whether as a new or experienced user, when establishing a physiological monitoring setup for a new study, it is essential to follow a systematic approach. Identifying the peripheral devices needed, the recording devices and software preferred, and ensuring synchronization to the magnetic resonance (MR) environment are all necessary steps to take. A detailed list of current devices, software, and methods for synchronizing data with neuroimaging acquisition is documented in our practices. We encourage readers to reach out via a Github Issue or by joining future meetings if interested in using the listed devices or they already do but have lingering questions that could be solved with discussion.

After acquiring and testing equipment and setup, in order to achieve high quality signals with fMRI data, a continuous time course (as opposed to starting and stopping physiological recordings for each scan) is recommended. It is in the users’ best interest to routinely assess the quality of the recordings, in case of subject movement or hardware malfunction, prior to starting the scan to ensure any issues can be fixed before the acquisition.

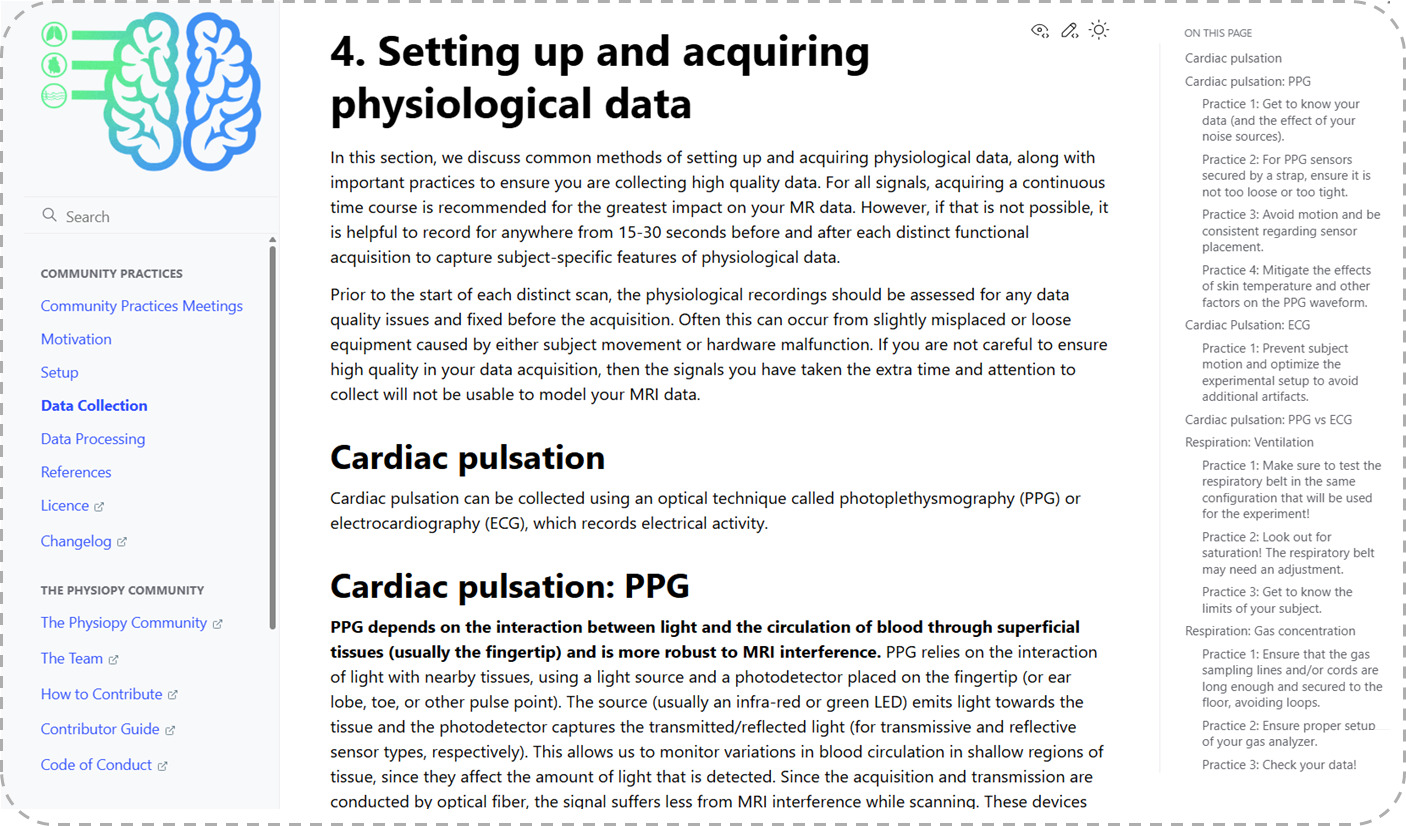

As mentioned, both PPG and ECG are commonly used methods in the neuroimaging community to capture cardiac signal variation.41 We provide detailed explanations into the distinction between the monitors, how the data is captured, and what specific cardiac insight the signal will provide for the user (see example excerpt in Figure 4). Additionally, we provide tips on getting familiar with data, what to look for, how to recognize noise, and tried and true recommendations for the best placement of these sensors. Both PPG and ECG have strengths and weaknesses; however, the choice between the two depends on the investigators’ intended use of the data and the concomitant MR sequence.42 We provide more detail on the pros and cons of each sensor as well as how these might compare to MRI-captured cardiac data.

When utilizing respiratory physiological data, the use of ventilation or gas concentration also depends on the research questions and signals of interest to investigate. Ventilation is typically monitored using a respiratory belt around the participant’s chest or diaphragm. The positioning of the belt can dictate how the signals are captured so baseline testing and consistency across scans are important to ensure high quality data. More detail on sources of noise, the limits and potential pitfalls of these recordings are detailed in our community practice documentation.

On the other hand, gas concentration studies are used to focus on CO2 and oxygen (O2) concentrations and how they might influence the BOLD signal through vasodilation and vasoconstriction, respectively. Information related to the level of blood gasses is an important factor when analyzing fMRI data. An increase in arterial CO2 levels is known to have vasodilatory effects, driving large variability in blood flow and the BOLD signal.43,44 Although O2 levels are known to have mild vasoconstrictive effects on the cerebrovasculature, these O2 levels can directly influence BOLD signal contrast.45 Practices to consider when collecting this data are included in our community practices to ensure that the highest possible quality of data is acquired, with specificity and sensitivity tailored to the research question at hand.

Processing and Leveraging Physiological Data in Neuroimaging

By following our provided community practices, the user will have ideally continuously recorded physiological data throughout the entire scan session and have trigger data from synchronization to indicate when scanning occurred. It is useful to organize and standardize the format of the resulting physiological data files along with any neuroimaging files acquired concurrently. Phys2bids25 can be used to organize the various physiological traces that were collected and restructure the data into an easy to use and standardized format. When analyzing the effects of physiological data (cardiac pulsation and respiration) in fMRI signal changes, several complementary models and methods may exist. Each approach has its own strengths and limitations, ranging from specific denoising capabilities to the complexity of the calculations and need for manual input on the signals collected. Our practices provide insight into many of the most commonly used data-driven46–49 and model-based1,7,9,43,50–53 methods and provide pros and cons to each approach. Ultimately, researchers should carefully select and validate the appropriate approach based on their specific research questions and the characteristics of their data.

Discussion

We believe that our live documentation will be of interest not only to those interested in utilizing physiological data in a neuroimaging context, but also as an example to any communities who may benefit from an analogous collective documentation of their practical expertise. While the goal of our practices is to remain toolbox-agnostic, compiling community consensus procedures and recommendations for physiological signal data provides the field with a wealth of knowledge that stems from years of collective experience in these areas. Much of this knowledge has existed in research labs for decades; however, researchers starting out in this field are more likely to be successful if they are in contact with people working in it. Studies that lack expertise in physiology could lead to suboptimal data acquisition and interpretation which in turn could affect the removal of possible confounding factors, ending in faulty conclusions. Building an accessible and practical resource, alongside a structure in place to keep it up to date with current practices, allows the dissemination of this knowledge and facilitates discussions on defining community standards. Physiopy was uniquely positioned to build a resource of this stature due to its diverse community consisting of both seasoned experts and graduate students and postdocs who have spent their careers collecting physiological data for neuroimaging experiments.

Leveraging a community to endorse methodological recommendations is not feasible for individual researchers or research groups, as it requires a collection of diverse expert knowledge and practical experiences over many decades. While it is not too different from the traditional approach of compiling so-called “white papers54–57”, instead of a traditional manuscript, we opted for a “live” resource due to its distinct advantages, especially in a fast-evolving and methodologically complex field. Community-based live resources provide consensus based up-to-date information that allows us to continually make changes and add information that will help the reader and community if new evidence, tools, or best practices emerge. Compared to traditional manuscripts, there is a unique emphasis to leverage the scientific community and field-wide concerns through transparency and collaborative efforts. As recommendations may evolve over time, providing versioning for transparency will allow researchers to be able to track the changes made and gain a full understanding of why the current recommendations exist. Lastly, a live resource is the epitome of a publication that best incorporates and encourages community feedback and iterates to stay current and peer reviewed, as well as encouraging new and diverse voices to express doubts and new points of view. Using a platform such as Git allows for version control to preserve static points in the field while keeping the resource up to date with current practices. Additionally, these resources are readily accessible through open-access platforms that are dynamic, interactive, and easy to navigate and provide feedback. By providing feedback through these platforms, it is straightforward and transparent to keep track of contributors and their respective contributions.

However, since live resources do not fit neatly into standard scientific publications, work like this is often not as rewarded within research even though highly valuable to its practitioners. Live resources can complement traditional peer-reviewed publications by offering an agile, transparent, and community-driven mechanism for sharing and refining practices over time. The neuroimaging community has seen great success in the management and engagement of resources like this as demonstrated by exemplary efforts such as The Turing Way58 and Open Brain Consent.59 In general, open science initiatives have shown great promise focusing on methods transparency, scholarly communication, team science, and collaborative research culture.60 Here, we wish to suggest that such live resources can complement traditional academic publishing: the latter can provide crucial visibility to open science efforts and important recognition in the form of authorship for volunteer contributors.

Resources like the Physiopy community practices have the potential to meaningfully influence and elevate standards across the field—setting benchmark expectations for data acquisition, quality control of physiological acquisition, and reporting practices. By consolidating community knowledge and consensus into an openly available, versioned document, this resource serves as an early but important step toward a broader, field-wide standard akin to a Committee on Best Practice in Data Analysis and Sharing (COBIDAS) guideline61 specific to physiological data collection in neuroimaging. With increasing concerns around reproducibility in neuroscience and related disciplines, transparent, well-documented, and standardized workflows are more important than ever, and reproducible science not only relies on sharing data and code, but ensuring that procedures used to collect, process, and interpret that data are consistent, interpretable, and replicable across labs and over time.26

Community-driven resources play a critical role in building consensus among users and promoting the harmonization of methods, alongside reducing the hidden variability in data collection protocols. By fostering transparency and collaboration, these efforts enable more reliable, reproducible, and scalable scientific progress. A sustained and genuine commitment to open science is the most effective path forward for advancing knowledge in a more attainable and inclusive manner. It also strengthens the broader scientific ecosystem by encouraging shared learning and continuous improvement for all involved, positively influencing career advancement.62 These contributions should be recognized as vital scholarly outputs that propel the field forward. They embody the values of openness, collaboration, and shared responsibility for the collective progress of science. However, maintaining a resource such as this comes with its own set of limitations and challenges. This effort is powered entirely by a volunteer community, often composed of early-career researchers - particularly graduate students - whose time in the field, and therefore contribution to Physiopy, can be relatively short. The transient nature of this workforce makes long-term sustainability difficult, despite the clear impact and value of the work. However, these challenges are not a reflection of the work’s importance or utility. More often, they stem from uncertainty about how to get involved, or a perception that contributing to community-driven efforts may not directly benefit one’s career. In reality, participating in open-source community-based initiatives like this offers tangible benefits at every career stage.

Early career researchers can build technical skills, grow professional networks, and gain visibility in the field.63 Mid-career scientists can contribute their experience while shaping evolving standards, and senior researchers can mentor, provide their expertise, and help align grassroots efforts with broader institutional and disciplinary goals.64 Training in software development and coding equips researchers with crucial technical skills while reinforcing the value of well-documented, reusable code. This not only elevates the overall quality of academic software65 but also signals to early-career scientists the importance of maintainable, open tools as foundational to modern research practice.66 Regardless of long-term career goals, involvement in these communities demonstrates a commitment to open, collaborative, and reproducible science—values that are increasingly recognized and rewarded in academia, industry, and beyond. To ensure the continued growth and impact of resources like this, we need broader support, recognition, and funding for community-driven work. Internally, Physiopy’s governing bodies aim to support knowledge transfer between new and longstanding contributors while growing awareness and usage within the broader research landscape. Sustained investments such as these help transform collective knowledge into a lasting infrastructure that benefits the entire field.

Future Development

We aim at expanding and improving upon the information provided with a large-scale goal of serving and engaging the entire neuroimaging community, as well as obtaining input from other communities routinely collecting physiological data, even if not experienced with neuroimaging. We are constantly working to improve how we obtain feedback, increase meeting attendance, and improve how we share our findings with the field.

Our live resource will continue to be a version-controlled, collaboratively maintained document that will reflect emerging evidence, methodological advances, and community consensus. By providing a static manuscript promoting and supporting the work we have done, our live resource can remain current by incorporating updates as new information becomes available, often through transparent revision histories and community contributions. We expect to update our live document semi-annually with information from our ongoing community practices meetings. Eventually, we plan to elevate our live resource through collaboration with other bodies invested in neuroimaging best practices to obtain the endorsement of other stakeholders in physiological data usage. Aligning with our goals of expanding the principles of open and reproducible research for neuroimaging we aim to work with COBIDAS to develop the best practices in physiological data acquisition and processing with MRI data. Lastly, we are working on a proposal intended to extend the current BIDS specification to include updated standards for raw peripheral physiological data[6] and for peripheral physiological derivatives. This proposed format will flexibly handle physiological data and specific signal processing techniques, improving automated analysis workflows.

It is important to acknowledge that the current members of our community predominantly collect cardiac pulsation data through PPG and/or ECG monitors, and respiration data through ventilation or gas concentration, but there are many other physiological signal modalities we do not have documentation for. Moreover, the largest part of the community is more familiar with MRI than other neuroimaging techniques, although we aim at improving documentation for these other neuroimaging techniques as well. Our community is actively pursuing the next update to our live resource that will include discussions on data cleaning, signal repair, feature extraction, and quality control of physiological data including a library of visual examples for “good” and “bad” recordings and potential artifacts which may be encountered. We also intend to regularly update our established sections as more discussions occur, maintain up-to-date references, and provide links to relevant material that the reader may need to make informed decisions. We are also actively building information on modalities from smaller subsets within our communities using oxygen saturation, electrodermal, and electrogastrography data. Our membership also comprises groups who collect electrophysiological data such as electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and hope to provide information on the simultaneous collection of these modalities and the potential benefits these signals can bring to our understanding of physiological signal impact in neuroimaging. Lastly, future development of our live resource will incorporate expertise from other relevant communities, for example experts in physiology outside neuroimaging or industry representatives that build physiological hardware and software.

Conclusion

Acquiring physiological data during neuroimaging is essential for improving data quality and interpretability, enabling researchers to account for physiological fluctuations, investigate their relationship with neural activity, and monitor participant states in real time. Despite the field’s depth of practical knowledge, much of it has remained inaccessible to newcomers. To address this, the Physiopy community—comprising both experienced and emerging researchers—collaborated with field leaders to create a comprehensive, up-to-date, and community-driven resource, available at https://physiopy-community-guidelines.rtfd.io. This live resource provides guidance on setting up physiological monitoring systems, acquiring high-quality data, and analyzing cardiac and respiratory signals in the context of fMRI. While we are continuing to evolve and improve upon our live resource, we encourage the community to reach out and provide us with feedback and information that would be helpful to the broader user. Lastly, we encourage all neuroimaging researchers to consider collecting these data to more fully capture the variable human physiology inherent to imaging experiments.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the input from leaders and contributors from the Physiopy community. We would like to acknowledge detailed contributions from all our named authors for their help drafting and reviewing this document and our live resources.

Funding Sources

The authors declare no funding sources related to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.