Introduction

Pooling functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data across multiple sites can enhance statistical power and support the inclusion of more diverse and representative subject populations. However, these benefits can only be fully realized if acquisition protocols are standardized, transparent, and reproducible, thereby not introducing additional variance to the data. In current practice, most fMRI workflows depend on vendor-specific, partially opaque acquisition and image reconstruction pipelines. However, the scanner software is typically optimized for operator convenience rather than scientific rigor, making the protocols based on vendor-provided sequences non-portable, difficult to replicate, and poorly suited for cross-site harmonization.

As a result, the stability of the fMRI image formation process cannot be guaranteed across scanners from different MRI vendors—or even across different software versions on the same scanner. For example, Keenan et al.1 observed inconsistent flip angles (radiofrequency [RF] transmit amplitude) following a scanner software upgrade. Consequently, observed differences in functional measures between sites or over time may reflect systematic differences in protocol implementation rather than genuine biological variation, and make acquisition of new data with identical conditions impossible due to the inability to “roll back” to a previous software version. This lack of reproducibility also creates a barrier to innovation, as implementing new fMRI acquisition strategies within proprietary vendor environments is technically demanding and time-consuming.

This article describes a vendor-neutral, open-source, and fully harmonized fMRI protocol that addresses these challenges. Our acquisition protocol is implemented in Pulseq,2 an emerging open standard for describing MRI pulse sequences in a vendor-independent way. This allows for exact harmonization of the pulse sequence across vendor platforms down to the individual RF/gradient waveform level, which in turn ensures that important aspects of the acquisition, such as the nominal slice profile and choice of fat suppression method, remain constant across sites and over time. Equally important, Pulseq enables harmonization of the image reconstruction step: since the raw (k-space) data and coil calibration data are acquired in a known way, the image time-series can be reconstructed in exactly the same way regardless of which scanner it came from. This stands in contrast to vendor-specific product protocols, which often employ different—and typically opaque—techniques for parallel imaging (e.g., SENSE,3 GRAPPA,4 or deep learning-based methods) and image pre-processing. Pulseq therefore creates an opportunity for the fMRI community to standardize not only the pulse sequence, but also the image reconstruction algorithms and associated scanner and coil calibration scans.

We begin by outlining the fundamentals and current capabilities of the Pulseq framework, including how it enables rapid prototyping and deployment of custom MRI sequences across different vendor platforms, and ensures immunity to scanner software upgrades. This section is primarily intended for MRI pulse sequence programmers and protocol maintainers.

We then describe the implementation of our Pulseq fMRI protocol and the practical steps needed to run the sequence on two major MRI vendor platforms—Siemens and General Electric (GE). We also present traveling subject data that illustrate the feasibility of deploying our protocol in a multi-site research setting. Notably, these results show reduced cross-vendor variability in functional connectivity measures compared to standard vendor-specific (product) protocols.

Finally, we provide recommendations and additional resources for fMRI researchers seeking to incorporate Pulseq into their own experimental protocols and grant applications.

The Pulseq platform

The key technical component of our open-source protocol relates to the initial part of the image formation chain: the signal generation and the data acquisition steps, where we employ the Pulseq platform for vendor-neutral MRI pulse sequence programming. Pulseq is both a conceptual sequence representation, a file specification that encapsulates it, and a set of software tools for creating, analyzing, and executing sequence files. Here we attempt to clarify these concepts and provide MRI physicists or protocol maintainers with enough information to install and run Pulseq sequences on their scanner.

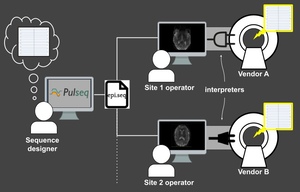

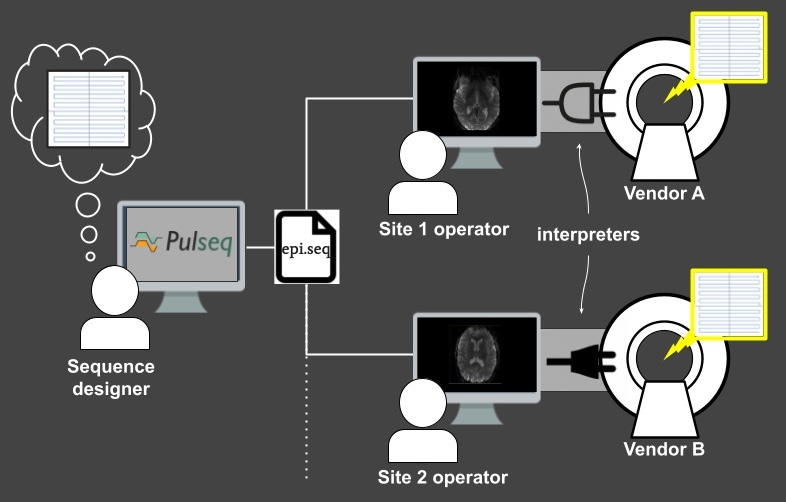

Overall workflow

The key idea behind Pulseq is to write the MRI pulse sequence specification to a vendor-neutral file (called a “.seq” file) that is to be loaded onto a particular MRI scanner via a vendor-specific interpreter (Figure 1). This file is plain-text and human-readable and contains the complete specification of every real-time event (RF pulses, gradients, signal acquisition) occurring in the sequence, according to an open specification.5 This same Pulseq file can also be used for other purposes, such as performing Bloch simulations, and generating sequence timing diagrams or precise k-space trajectories. The Pulseq standard itself is vendor-neutral and agnostic to the specifics of a particular vendor platform and the implementation details of the specific interpreter.

Once the Pulseq interpreter is installed on a particular scanner, different pulse sequences can be executed by simply selecting the appropriate sequence file from the user interface of the scanner console; the interpreter itself is sequence-agnostic. Importantly, maintaining Pulseq sequences across system software upgrades is simply a matter of recompiling the interpreter, since the sequence files are agnostic to the scanner software version. This greatly simplifies the task of maintaining fMRI protocols across scanner software versions.

A deeper dive into Pulseq

While this article focuses on a specific simultaneous multi-slice (SMS)-echo planar imaging (EPI) fMRI protocol developed and validated by the authors, researchers across the broader fMRI community may want to modify the sequence to suit their own needs. Whether modifying an existing Pulseq sequence or creating one from scratch, it is important to understand how Pulseq represents the various elements of the sequence, what software tools are available to implement them, and how to ensure compatibility with a particular scanner make and model. This section is intended to support that understanding. However, readers who are primarily interested in using the pre-configured fMRI sequence files provided by the authors may choose to skip it.

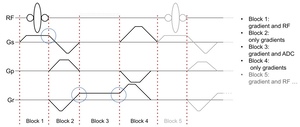

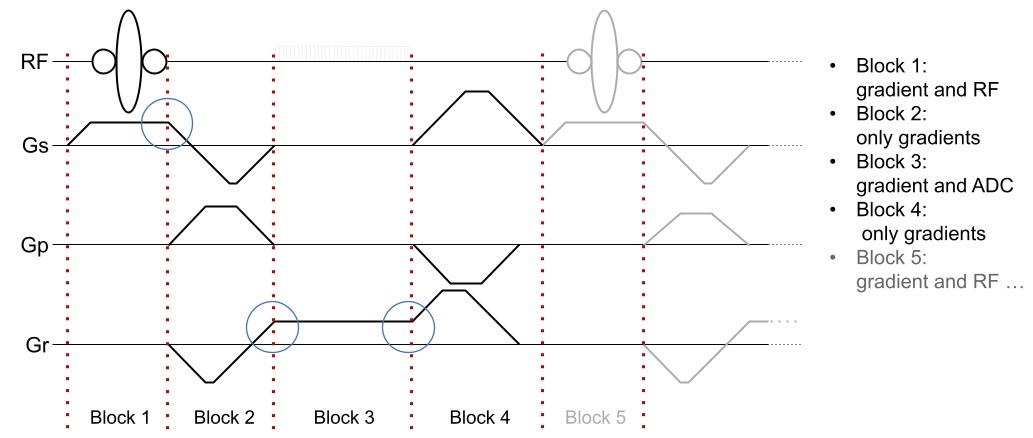

Sequence representation

In Pulseq, an MRI pulse sequence is represented as a series of sequential, non-overlapping blocks (Figure 2). Each block can contain at most one RF pulse, one gradient waveform per axis, and one data acquisition (ADC) window. Apart from this constraint, and vendor-specific hardware limits on peak waveform amplitude, gradient slew rate, and transmit/receive (T/R) switching times, the sequence designer is free to choose where to place the block boundaries. This also means that a gradient event does not need to have zero amplitude at a block boundary, as long as no amplitude discontinuity is introduced. The sequence is defined explicitly, without formal relationships between blocks or higher-level constructs such as loops or defined repetition time (TR) intervals.

Software tools for creating Pulseq files

Apart from the ‘official’ MATLAB toolbox, sequence designers can choose from several alternative ways to create a Pulseq (.seq) file. pyPulseq6 is an open Python implementation of the MATLAB toolbox, and enables sequence creation in environments where it may be difficult to obtain a MATLAB license. Higher-level design tools also exist,7,8 however, the most common way to create Pulseq sequence files is to work directly with the MATLAB2,9 and Python6 toolboxes.

Defining sequence events

The core task for a Pulseq sequence designer working directly with the MATLAB or Python toolbox is to define the RF, gradient, and ADC events that make up the sequence. In both of these frameworks, each event is described using a small set of parameters encapsulated in a data entity (e.g. an object or a struct). For instance, an RF event must specify its start time relative to the beginning of the block (delay), the complex waveform samples in physical units (signal) and their corresponding time points (t), the frequency offset in Hz (freqOffset) or in parts-per-million (ppmOffset), and the phase offset in radians (phaseOffset). Additionally, system-specific parameters such as deadTime and ringdownTime, which reflect RF coil and amplifier switching behavior, affect the timing of the RF events. The sequence designer can either populate the fields of the structure directly, or use the helper functions provided by the chosen framework to generate common pulse shapes (e.g. sinc RF pulses).6,9 The same approach applies to gradient and ADC events that can be created using library functions or by directly populating the required parameters.

Assembling the sequence

Once the individual events have been defined, they need to be assigned to blocks and added to a sequence object. This process typically begins by creating an empty sequence object that is configured for a particular scanner hardware platform, followed by inserting blocks into that sequence object using the addBlock() member function. Blocks are added in the order of execution, and the Pulseq toolbox automatically manages the internal organization of the sequence for you. Although the Pulseq representation does not formally define relationships between blocks, it is common practice to use a loop structure when assembling the sequence in code. Examples of MATLAB and Python code for creating many basic and advanced sequences are freely available on Github; some of these sites are listed in Table 1. Once the sequence object is populated with blocks, it can be plotted for visual inspection and written to a file.

Ensuring compatibility with scanner hardware constraints

It is the responsibility of the sequence designer to ensure that the various RF/gradient/ADC events specified in the .seq file are compatible with the scanner hardware configuration. To aid with this task, Pulseq defines a list of generic hardware parameters that are set by the sequence designer. These include: RF amplitude, dead time, ringdown time, and raster time; gradient amplitude, slew rate, and raster time; ADC dead time and dwell time; and block duration raster time. The Pulseq toolbox includes both internal and user-callable checks to ensure that the sequence object adheres to these settings. For a sequence to run on a specific scanner, its design specifications must be equal to or lower than the actual capabilities of that scanner.

Availability of Pulseq interpreters on various MRI vendor platforms

The Pulseq standard is built on a strict separation between the pulse sequence definition (encapsulated in a Pulseq object or .seq file) and the system or software that ‘consumes’ it. This has enabled both the research community and scanner vendors to independently develop various third-party Pulseq tools, including the interpreters that now exist on multiple vendor platforms. Table 2 lists the various interpreters that we are aware of at the time of writing.

These interpreters are at various stages of development, and we encourage the reader to contact the respective developer or their vendor representative for the most up-to-date information. However, some general observations can be made. First, several interpreters have been developed by community researchers using only the vendors’ standard pulse sequence application programming interfaces (APIs)—IDEA for Siemens, EPIC for GE, and PARADISE for Philips. These interpreters are openly available within each vendor’s respective research user community. The fact that they rely solely on widely accessible development tools, combined with their open availability, supports the ongoing development and long-term sustainability of these interpreters. Another important benefit of implementing the interpreters using the vendor APIs is that Pulseq sequences can be plotted and simulated using the standard vendor tools. Figure 5(a) shows an example of this, where our SMS-EPI sequence is simulated and plotted using GE’s native sequence tools (WTools and Pulse View, respectively).

Second, some interpreters require an intermediate sequence representation before execution can proceed. This is the case for GE scanners, where the internal sequence format depends on recognizing repeating subunits, such as a sequence TR or a magnetization preparation segment. Currently, users can convert sequences into this intermediate form manually using openly available tools,13 or take advantage of the recently introduced Pulserver framework14 that automates the conversion process. In addition to simplifying sequence deployment, Pulserver also enables more interactive sequence prescription directly on the scanner console.

Third, vendors have generally demonstrated strong support for the Pulseq platform, as evidenced by the development of vendor-authored interpreters and the substantial technical assistance provided to community developers.14,15 Vendors appear to recognize the value of supporting their research users through Pulseq, both as a rapid prototyping tool and as a means to facilitate protocol harmonization across sites.

Lastly, as broad vendor platform support continues to emerge—each with its own software and hardware constraints—there will be a growing need for free and open-source software tools that enable researchers to verify the compatibility of a Pulseq sequence with the available scanner hardware. Developing such tools offers an opportunity for community researchers and developers to actively contribute to the Pulseq project.

Patient safety and system hardware protection

Deploying an MRI pulse sequence requires careful consideration of both subject safety and hardware protection. Subject safety focuses primarily on limiting RF power deposition (specific absorption rate [SAR]) and peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS), while hardware protection involves ensuring the integrity of the RF and gradient subsystems. In sequences developed using vendor-provided pulse programming toolkits (APIs), these safety checks are typically handled either automatically by the scanner or manually by the sequence designer through API-accessible safety routines. The Pulseq interpreters also benefit from these built-in system and API-level safety mechanisms. Additionally, Pulseq allows SAR and PNS to be estimated during the sequence design phase—before the sequence is deployed to the scanner. Here we summarize the various safety checks employed by Pulseq, focusing on the two vendor platforms used so far in this project (Siemens and GE).

RF power deposition (SAR)

To our knowledge, all human MRI scanners are equipped with hardware for monitoring RF power deposition. This hardware monitor is always fully engaged, for Pulseq and non-Pulseq sequences alike. In addition, the Siemens and GE interpreters use the API safety routines in the same way as native (product/research) sequences. The Pulseq sequence designer can perform additional checks during the design phase to reduce the chance that the sequence will trip the scanner’s built-in and API SAR checks, such as comparing the nominal RF power to a known reference scan; planning ahead in this way is particularly useful for multi-site studies.

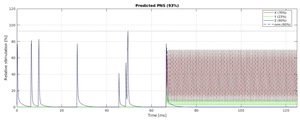

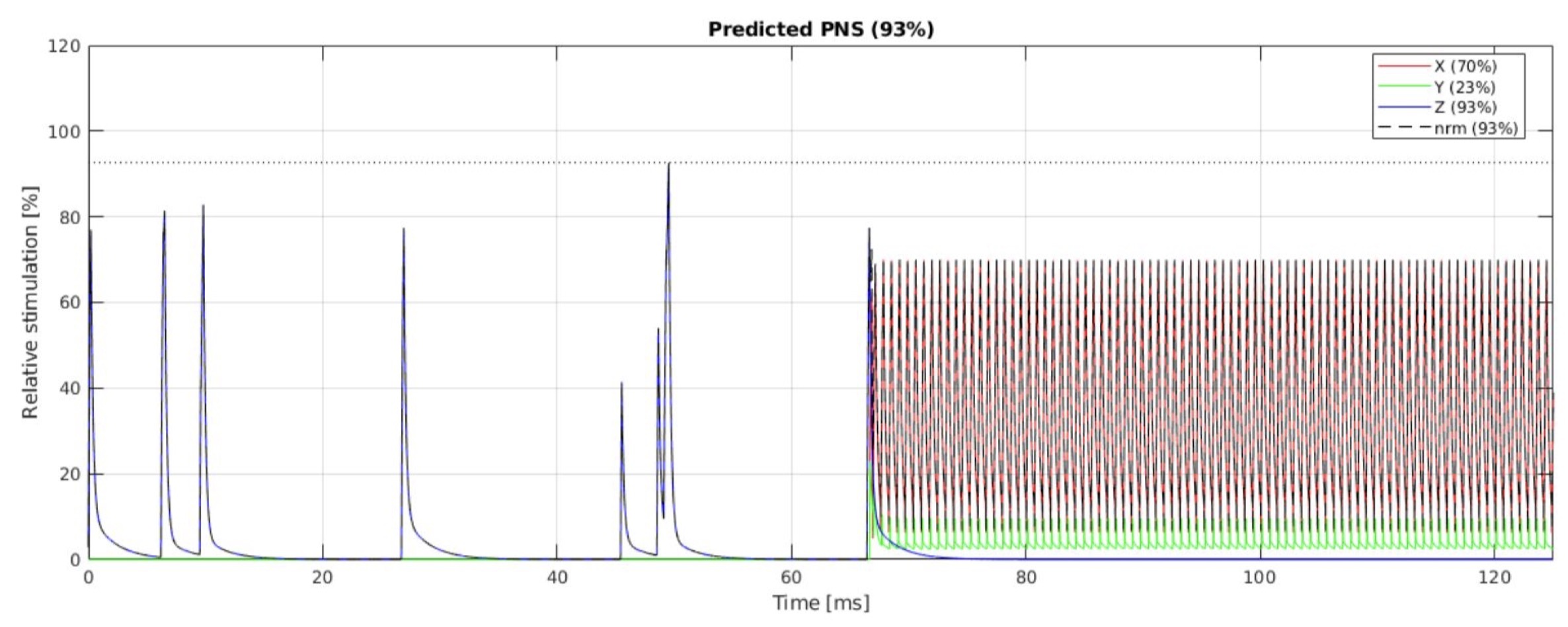

Peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS)

The sequence designer can (and should!) model PNS during the design stage using either the SAFE model for Siemens scanners,16–18 or the IEC nerve impulse response function model for GE scanners.19 Open MATLAB implementations by our group and others of these PNS models are freely available on Github.16,20 In addition, some interpreters (e.g., Siemens) perform online PNS monitoring, while others are planning to do so in a future release (e.g., the community-developed GE interpreter). Developing a vendor-neutral, standardized PNS model that can be employed across a broader range of vendors and scanner models is an open problem.

Hardware protection

Like pulse sequences implemented with the native API, the Pulseq interpreters rely on API-accessible safety routines to ensure hardware safety. For example, the GE API (EPIC) defines the subroutine minseq to calculate the minimum allowable TR for a given gradient waveform. RF subsystem checks are performed in a similar way. In this way, the vendor does not need to expose any proprietary details about the underlying safety checking algorithms or hardware performance; only the subroutine output (e.g., minimum allowable TR) is needed by the interpreter. This also means that responsibility for hardware protection rests solely on the interpreter, and not on the sequence designer.

Proposed vendor-neutral, open-source fMRI protocol

Pulse sequence implementation

We implemented a BOLD SMS-EPI sequence with parameters that closely match the ABCD protocol21: 2.4 mm isotropic resolution, 90x90 matrix size, 60 slices without gaps, SMS factor 6, 1x6z2 CAIPI sampling pattern,22 TR 0.8 s, partial Fourier factor 0.8. We created the various sequence events, and assembled the Pulseq sequence object, using the MATLAB Pulseq toolbox. The MATLAB scripts are freely and openly available on Github,23 enabling users to modify the acquisition parameters to suit their own needs.

Figure 5(a) shows the timing diagram for one sequence TR, which consists of fat saturation using a minimum-phase Shinnar-Le Roux (SLR) pulse,24 SMS excitation using SLR sub-pulses with phase offsets following the scheme by Wong,25 and ramp-sampled EPI readout. To reduce the risk of PNS during the EPI train, we derated the slew rate to ensure that the predicted PNS, based on the nerve impulse response model19 stays below 80% of the stimulation limit (normal mode). The sequence is RF-spoiled to suppress steady-state signal contributions from spin- and stimulated-echo pathways.26

Image reconstruction

To reconstruct images from the acquired raw (k-space) SMS-EPI data, the user is free to choose from several available image reconstruction pipelines. The HarmonizedMRI development team has implemented both 3D SENSE27 and slice GRAPPA28 SMS-EPI reconstructions in MATLAB that are part of the QA protocol described below. Other community-developed implementations are also available.29–33 Figure 5(b) shows the results of reconstructing Pulseq SMS-EPI data using 3D SENSE27 implemented in BART.32 Figure 6 demonstrates that our Pulseq protocol achieves similar image contrast and overall image quality as the matched product protocols.

In our current workflow, image reconstruction is done with slice GRAPPA due to its fast computation speed and robust image quality, and zero-filling partial Fourier (PF) reconstruction. Other choices are possible, such as multi-coil reconstructions with spatial regularization, and homodyne PF reconstruction. The extent to which these image reconstruction and post-processing choices impact fMRI reproducibility is an open research question.

Results

Image quality metrics

To quantitatively assess overall image quality, we analyzed time-series data in phantoms and a volunteer obtained with both the proposed Pulseq SMS-EPI protocol and the vendors’ native (product) protocols on two vendor platforms (GE and Siemens). For the product protocols, images were reconstructed using the vendor-provided reconstructions available on the scanner. Figure 7(a) displays the ABCD quality metrics calculated for phantom data acquired on both a GE MR750 and a GE UHP scanner. These values are compared against reference values acquired in the ABCD study. We observe that Pulseq performs favorably against the vendor ABCD protocol. The higher SNR in the ABCD UHP acquisition is partly ascribed to the full ky coverage, as opposed to the fractional ky coverage on the MR750 and in the Pulseq acquisition. As the Pulseq acquisition is the same across scanners, SNR values are more similar across the two scanners as compared to the ABCD protocol.

Figure 7(b) plots the FWHM values for the product multiband sequences (blue) vs Pulseq implementation (red) in both GE and Siemens scanners, for resting-state data acquired in a traveling subject, with four repeats at each site. Full width at half maximum (FWHM) is a measure of spatial autocorrelation, with lower values being desirable (indicating higher resolution). It is seen that there is reduced variance across scanners and vendors with the Pulseq ABCD acquisition compared to the product ABCD acquisition (ABCD: Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development study21).

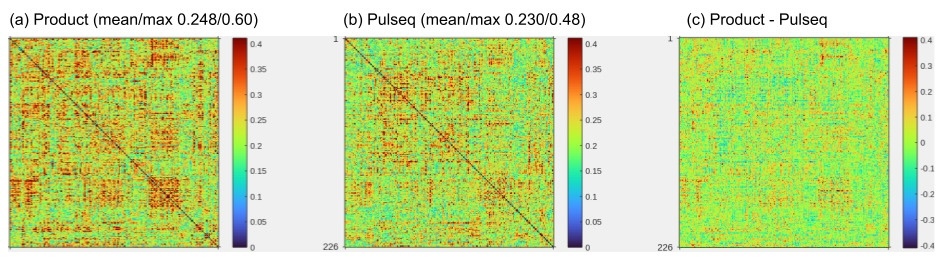

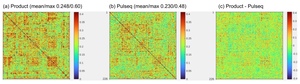

Cross-vendor reproducibility of resting-state functional connectivity

To assess the potential of our Pulseq fMRI protocol for improving cross-vendor reproducibility of resting-state fMRI metrics, we conducted two small traveling subject studies. In the first study, one traveling subject visited 5 separate scanners, and underwent four runs of a five-minute resting-state scan at each site. Figure 8 summarizes the results of this study. It is seen that the Pulseq average connectivity matrix is comparable to the Product connectivity matrix, and that the standard deviation has fewer regions of relatively high cross-scanner variation (though this may be due to subject effects). In other words, this data suggests that harmonizing the acquisition (with Pulseq) as well as the SMS-EPI reconstruction results in more consistent resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) metrics across these 5 scanners.

In the second study, 7 volunteers each underwent two separate scan sessions on different days and on different MRI vendor platforms (Siemens and GE). Each session consisted of a T1 anatomical scan and two 5-minute rest scans, one using the Pulseq protocol and the other the product protocol. In the same session we also acquired 4 repetitions of a block finger-tapping and visual activation task using both Pulseq and product protocols; analysis of the task data is ongoing and will be presented elsewhere. Figure 9 summarizes the resting-state analysis from this study. We observed that the within-subject, cross-scanner resting-state FC matrices tend to be more similar when using the proposed Pulseq protocol compared to the product protocols.

Functional connectivity methods

RsFC matrices were calculated for each scan using the CONN toolbox35 release 22.v240736 and SPM37 release 12.7771. Functional and anatomical data were preprocessed using CONN’s default preprocessing pipeline38 (minus slice time correction) including realignment, outlier detection, direct segmentation and MNI-space normalization, and smoothing with a 6mm kernel. In addition, functional data were denoised using CONN’s standard denoising pipeline38 including the regression of potential confounding effects characterized by white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) timeseries, motion parameters and their first order derivatives, outlier scans, session and scan effects and their first order derivatives, and linear trends within each resting state run, followed by bandpass frequency filtering of the timeseries between 0.008 Hz and 0.09 Hz. The rsFC matrices were calculated using the nodes from the Power functional network atlas.39

Example usage

To help users get started, we created a complete example showcasing the entire workflow — from data acquisition to generating an image time series. You can explore it here: https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/SMS-EPI/tree/main/example. The demo includes step-by-step instructions, links to all source code, and access to a sample dataset (available upon request via a Google form).

Incorporating Pulseq fMRI in your research: Recommendations and additional resources

Thus far, we have focused on the technical implementation of the Pulseq fMRI protocol and presented traveling subject data that demonstrate its scientific value. Based on the information provided in the preceding sections and the associated GitHub repositories, technically proficient users should be able to install the Pulseq SMS-EPI protocol, customize it as needed, and assess its suitability for their research. In this section, we provide additional guidance and recommendations for users at varying levels of engagement and pulse sequence expertise, from initial installation and testing to the planning and execution of multi-site research studies.

Quality Assurance (QA) protocols

To ensure correct installation of the proposed Pulseq fMRI protocol and consistent performance across sites, we recommend that the user executes two QA protocols. The first is described in detail in Chen et al.40 and involves scanning a uniform ball phantom (preferably FBIRN/EZfMRI) using a set of separate Pulseq sequences available at https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/qualityAssurance/tree/main. The data is then processed using a set of MATLAB scripts that are also available at that Github site, and that produce performance metrics including signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), temporal SNR, and EPI ghost to signal ratio.

We also recommend calculating quality metrics using the ABCD QC protocol (which is based on the fBIRN protocol) on an fBIRN/EZfMRI phantom, as implemented in the ABCD study (https://github.com/ABCD-STUDY/FIONA-QC-PHANTOM). Besides the metrics mentioned above, this protocol also calculates RDC (radius of decorrelation), and FWHM for each spatial axis; both of which can help detect issues in image quality.

For both QA protocols, we further recommend that the user compare their results against the product protocol on their scanner, and against normative values that we provide.

Reproducibility best practices

To maximize transparency and reproducibility, we recommend that users follow standard reproducibility best practices, by:

-

Using and documenting a specific version of the framework used to create the .seq file.

-

Using and documenting a specific version of the interpreter.

-

Using and documenting a specific version of the QA protocol sequences.

We also recommend that users consider preregistering their study with a link to a specific version of the sequence (e.g., Zenodo DOI linked to a specific Github commit), for maximum reproducibility. For further guidance on making MRI pipelines more reproducible, we refer the reader to a recent review article by Tamir et al.41

Getting technical help and connecting with other users

Our open fMRI protocol is part of a broader ecosystem of open-source software for sequence design and image reconstruction, and vendor-specific Pulseq interpreters that are typically only available within each vendor’s research user community. As such it can be difficult for the resource user to know where to look for guidance on specific components of the proposed fMRI workflow, particularly in a multi-vendor, multi-site setting. Here we provide a few resources to help orient the user. For help getting started with the proposed SMS-EPI fMRI protocol that is the focus of this article, see https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/Functional.

General help with Pulseq

The formal Pulseq specification and the source code for the MATLAB toolbox are available at https://github.com/pulseq/pulseq. That site also contains an active discussion forum and a bug report forum; these are named ‘Discussions’ and ‘Issues’, respectively, following the usual Github platform convention. In addition, several recorded Pulseq talks are available online.

Pulseq user group meetings

Beginning in September 2025, we will host a regular virtual meeting for the Pulseq user community, to provide technical help in an ‘office hour’ format and give community researchers an opportunity to present and discuss their work in an informal setting. This meeting is open to everyone – a registration link is provided on the project home page (https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/Functional).

Direct help from members of the HarmonizedMRI study team

We are making a fee-based service package available to funded fMRI studies that includes assistance with protocol installation and QA, protocol maintenance across scanner software upgrades, and consultation. We suggest that PIs budget for this service package in their grant proposals; suggested template text to include in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Budget Justification section is described below.

Writing a multi-site research study grant proposal

To assist Principal Investigators (PIs) in integrating the proposed fMRI protocol into future multi-site research studies, we offer example/template text suitable for inclusion in various sections of a grant proposal.42 While the template is primarily designed for NIH applications, it can be adapted to meet the requirements of other funding agencies. Users are encouraged to tailor the text as needed to align with their specific project goals and proposal style. The templates include the following:

-

Scientific and technical rationale for using Pulseq (Research Plan section)

-

QA report from all study sites (Research Plan or Facilities & Resources)

-

Budget justification section:

-

Funding for FBIRN phantom (for QA protocol)

-

Tiered support subscription service (optional)

-

-

Human subjects protection section (Pulseq-specific statements regarding safety)

-

Letter of support from MRI scanner manufacturer(s) (optional)

While optional, we recommend including letters of support from the vendors. From the vendors’ standpoint, executing a Pulseq sequence is equivalent to running any custom pulse sequence developed by a research user through the vendor’s programming APIs. Consequently, each scanner participating in a proposed multi-site study must have an active research license. Provided this requirement is met, vendors should be able to furnish a letter of support granting permission to run the Pulseq fMRI protocol, confirming access to the standard technical support channels available to research users on that platform, and—ideally—endorsing the scientific rationale of both the Pulseq fMRI protocol and the broader Pulseq initiative. To facilitate this process, we provide a sample letter of support that incorporates these elements, that users are free to adapt to their own needs.

Preparing the IRB protocol

Pulseq-specific IRB protocol

As noted above, Pulseq sequences are implemented using the standard pulse sequence programming environments provided by each vendor (e.g., EPIC for GE, IDEA for Siemens) and are subject to the same safety checks and hardware constraints as any other research sequence. We nevertheless recommend preparing a dedicated IRB protocol specifically for general scanning with Pulseq sequences. This protocol only needs to be created once and can significantly reduce administrative burden by eliminating the need to repeatedly explain the nature and risks of Pulseq in each new study. The Pulseq IRB protocol should be used in conjunction with the study-specific IRB protocol, and participants should provide informed consent for both.

Joining the University of Michigan multi-site (single) IRB protocol

An alternative for researchers based in the United States is to cede IRB oversight to the University of Michigan. This eliminates the need to prepare a site-specific Pulseq IRB application, and further encourages scientific collaboration and data sharing between research sites. The University of Michigan multi-site (“single”) IRB protocol covers general Pulseq scanning including both functional and structural MRI, and is currently in preparation. We share the scientific protocol text publicly,43 which can also be used as a template for preparing a site-specific Pulseq IRB application. The University of Michigan Pulseq IRB protocol should be used in conjunction with the study-specific (typically local) IRB protocol, and participants should provide informed consent for both.

Discussion

The proposed Pulseq fMRI protocol enables identical sequence execution and image reconstruction across multiple scanner platforms, providing highly reproducible conditions for multi-site fMRI research. While this approach minimizes variability, some inter-site differences inevitably remain—for example, variations in receive coil arrays and RF transmit coil configurations. Another source of variability is the B0 shimming protocols employed by different vendors; however, recent efforts by our group44 and others45 have begun to address this issue. A more subtle factor is the accuracy of gradient trajectories, which can be influenced by differences in gradient hardware performance and vendor-specific eddy current compensation routines. Developing a standardized method for measuring gradient trajectories—and evaluating their impact on the quality of the derived functional maps/measures—remains an area for future research.

As currently implemented, our Pulseq fMRI protocol only allows limited prescription-time flexibility. While the field-of-view (FOV) can be freely moved and rotated, most other acquisition parameters are fixed including the matrix size and SMS acceleration factor; modifying these parameters requires editing the MATLAB script and creating a new .seq file. In some imaging settings, notably during the course of a study, fixing the FOV and matrix size can be an important beneficial feature to ensure maximum reproducibility. On the other hand, during initial image quality assessment and protocol optimization, it can be beneficial to allow a more interactive sequence prescription, ideally using the vendor’s built-in user interface (UI). Pulserver14 is a recent effort to provide this functionality, but has so far only been demonstrated on one vendor platform. Another approach is the gammaSTAR framework,46 which uses a dedicated user interface and sequence generation backend. Ongoing work is exploring the use of these frameworks to support interactive, vendor-neutral MRI protocol development.

At present, our fMRI protocol includes offline image reconstruction, which is generally sufficient for functional imaging studies. However, clinical research settings can benefit from online (on-the-host) image reconstruction and display similar to the built-in sequences, e.g., as an immediate image quality check and to integrate directly with the standard DICOM image workflow and storage. To our knowledge, most MRI vendors now offer containerized, online image reconstruction environments that allow research users to plug their own custom algorithms into the scanner’s image reconstruction and display pipeline. Together with a more interactive sequence prescription as just described, these containerized environments will enable vendor-neutral (f)MRI protocols that have a similar ‘look and feel’ as built-in protocols.

The vendor interpreters we have tested so far (Siemens, GE) do not yet allow real-time sequence updates, as would be necessary for, e.g., navigator-based prospective motion correction. While existing fMRI protocols in routine use rely on retrospective image co-registration, prospective motion correction may have certain advantages, such as reduced slice interpolation artifacts. To our knowledge, the vendors’ real-time sequence update mechanisms are available to their research users (including the Pulseq interpreter developers), making it possible to modify the Pulseq interpreters accordingly. Implementing and testing real-time sequence updates for Pulseq remains an area for future research.

The current SMS-EPI acquisition and reconstruction methods we offer are based on well-established approaches, but there remains potential for further improvement. We anticipate—and actively encourage—the research community to use this implementation as a foundation or benchmark for developing improved fMRI protocols. Furthermore, as improved methods become available, individual components of our workflow can be replaced with state-of-the-art alternatives. For example, in our current Pulseq implementation, the block boundaries within the EPI train are centered on the ky/kz blips. This choice is robust but memory-intensive, because each blip is shared between neighboring blocks and must therefore be represented with unique gradient shapes rather than a single scaled trapezoid. On the reconstruction side, advances in spatio-temporal reconstruction are likely to yield more robust functional measures and may require frame-to-frame variation in ky/kz sampling patterns. Other groups have also implemented fMRI and EPI sequences in Pulseq,47,48 that may be better suited for such emerging acquisition and reconstruction strategies.

The data presented here do not identify the specific sources of vendor-related differences in functional measures—whether they arise from hardware, pulse-sequence implementation, or reconstruction algorithms. Determining the relative contributions of these factors is an important direction for future research. In particular, if vendor-specific sequence components that lie outside the MRI physicist’s control (e.g., fat-suppression method, slice profile) prove to have only a minor impact on reproducibility, future multi-site (f)MRI studies could focus harmonization efforts on high-level acquisition parameters and the reconstruction stage. Several open-source reconstruction packages are available to support such efforts, including BART,32 MIRT,49,50 grappa-tools,29 and the slice GRAPPA MATLAB implementation developed for the present work.51

In addition to the patient and scanner safety considerations discussed above, the use of Pulseq-based sequences for clinical diagnosis requires assurance that the resulting images are geometrically accurate and free of artifacts beyond those expected from comparable product sequences. Basic system-dependent factors—such as the sign conventions for gradient waveforms or the RF frequency offset—vary across vendors and, if not correctly handled, can lead to left–right image flips, excitation of incorrect slices, or inadequate fat suppression. To address these issues, a standardized Pulseq calibration protocol will be needed to characterize these vendor-specific properties of an MRI system. The Pulseq interpreter would then use this information to ensure that any .seq file is executed exactly as intended.

Conclusion

The proposed fMRI protocol harmonizes all software-related aspects of an SMS-EPI protocol, from data acquisition to image reconstruction. The protocol is fully open source, and has so far been tested on two vendor platforms (Siemens and GE) with more expected in the near future. We provide resources to help researchers draft grant and IRB applications that use the proposed Pulseq fMRI protocol, and customer support for sites without a dedicated MRI physicist.

Data and Code Availability

Code for Pulseq sequence file generation and image reconstruction: The code used in this manuscript to create the Pulseq sequence files and reconstruct the data to form time-series images, is publicly available. The home page for this project, https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/Functional, contains links to this code as well as a general overview of the project. A complete, tutorial-style, example of using this code is available at https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/SMS-EPI/tree/main/example.

The versions used to collect the data presented here are:

-

Pulseq sequence files: https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/SMS-EPI/releases/tag/v0.2.0 (sequence generation script is ./sequence/main.m)

-

Image reconstruction: https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/utils/releases/tag/Harmonized_fMRI_r0

Pulseq interpreters: Source code for the vendor-specific GE and Siemens Pulseq interpreters used in this manuscript is freely available within the respective vendor research user communities. The GE interpreter source code is available at https://github.com/GEHC-External/pulseq-ge-interpreter and research users can request access via their local GE representative. Siemens research users can acquire the Pulseq Interpreter under the conditions of the Customer-to-Customer Partnership (C2P, a.k.a. C2P) program, either electronically via the TeamPlay web service or by contacting the authors at pulseq.mr@uniklinik-freiburg.de.

The interpreter versions used to collect the data presented here are:

-

GE interpreter: tv6 v1.9.0 and v1.9.1

-

Siemens interpreter: v1.4.3

Example text for NIH grant and IRB applications: The project home page (https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/Functional) contains a link to the example grant and IRB text templates mentioned in this manuscript. This text is provided at no cost and without constraints. Users therefore are free to adapt the text to suit their own needs, and to use it for any purpose.

Example volunteer brain fMRI data set: The data set used in the example at https://github.com/HarmonizedMRI/SMS-EPI/tree/main/example is available upon request (via a Google form, available at that site). The data set consists of raw, multi-coil, SMS-EPI k-space data. Our current IRB does not permit publicly sharing raw k-space data since such data cannot be de-faced or otherwise made fully anonymous. The user must agree to not attempt to identify any study participants.

Funding Sources

Funding for this project is provided by NIH grants U24-NS120056 and R03-EB038095.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose in connection with the content of this manuscript.

_rf_and_(b)_gradient_event_creation_using_the_pulseq_matlab_toolbox._once_t.jpg)

_proposed_pulseq_sms-epi_sequence_simulated_in_ge_s_sequence_simulator_pulse_studio._th.jpeg)

_sms-epi_protocols_(top)_and_our_proposed_pul.jpeg)

_fbirn_phantom_metrics_for_ge_mr750_(top)_and_ge_uhp_(bottom)_mri_scanners__using_eithe.jpeg)

_matrices_in_the_same_subje.jpeg)

_rf_and_(b)_gradient_event_creation_using_the_pulseq_matlab_toolbox._once_t.jpg)

_proposed_pulseq_sms-epi_sequence_simulated_in_ge_s_sequence_simulator_pulse_studio._th.jpeg)

_sms-epi_protocols_(top)_and_our_proposed_pul.jpeg)

_fbirn_phantom_metrics_for_ge_mr750_(top)_and_ge_uhp_(bottom)_mri_scanners__using_eithe.jpeg)

_matrices_in_the_same_subje.jpeg)