Introduction

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become a cornerstone of cognitive neuroscience, offering detailed insights into the neural basis of memory, attention, and perception. It has also played a key role in language research, shedding light on how the brain processes speech and text. Within this field, studies of word processing have used fMRI to explore how written and spoken words are perceived and interpreted. While these studies have advanced our understanding of language, most rely on group-level analyses, potentially overlooking meaningful individual differences. Within this paper we present the Austrian NeuroCloud (ANC) language study dataset1 that resumes research on word processing but follows a precision magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) approach and was created for investigations on the single subject level.

So far, great efforts have been made to link orthographic, phonological, and semantic processing to distinct but partially overlapping brain regions. Orthographic processing is associated with activation in the fusiform gyrus,2,3 the broader ventral occipitotemporal (vOT) cortex,4,5 particularly within the visual word form area (VWFA),4–8 and in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG).4 Semantic processing has been linked to activity in several regions, including the IFG, in the superior temporal sulcus (STS), angular gyrus (AnG), posterior middle temporal gyrus (pMTG), precuneus, and vOT.3,4,6,9–11 Phonological processing has been associated with the temporoparietal cortex (TPC), the IFG, the AnG, precentral gyrus, supramarginal gyrus (SMG), superior temporal gyrus (STG), planum temporale, and inferior parietal lobule.2–5,10–13

However, there is no clear consensus across studies regarding which regions support which processes. It also remains uncertain whether some areas are truly specific to a single process or function as shared, multi-purpose hubs. Furthermore, the functional subdivisions of many regions are unclear. For instance, the functional organization of the IFG is still debated. While Vigneau et al.10 associated the pars opercularis with semantics, Glezer et al.4 linked it to orthographic processing, and Pattamadilok et al.3 to phonological processing. A recent meta-analysis14 placed the posterior IFG within the dorsal language stream, based on its role in syntactic processing, but found no phonology-specific activation in the IFG. The authors also noted challenges in disentangling semantic and phonological contributions in temporoparietal regions, such as the SMG and AnG. Further, Hodgson et al.15 suggest that shared regions of semantic and phonological networks may support domain-general control rather than specific processes.

Another example is the visual word form area (VWFA), which is widely recognized for its role in orthographic processing and is consistently activated during visual word recognition.16 As it only responds to visual input, the VWFA is not considered to be part of the core language network.17 However, some findings suggest that the VWFA may not be exclusively visual: activation during auditory language tasks likely reflects top-down influences from higher-order language areas.16,17

These inconsistencies may, in part, stem from methodological limitations that have only recently begun to be addressed. Hodgson et al.15 identified advances in data quality, larger datasets, and improved analytic techniques as the means to potentially distinguish between language sub-networks. Similarly, Pattamadilok et al.3 noted that conventional fMRI often suffers from signal dropout in the anterior and ventral IFG, potentially contributing to conflicting findings. Dehaene and Cohen16 pointed out that group-level analyses may obscure functional distinctions between neighbouring regions. Meanwhile Li et al.17 emphasized that interindividual variability remains underexplored, despite its potential to explain inconsistencies in findings. Addressing neural variability is essential for improving the reliability and interpretability of fMRI research. Despite longstanding recognition, individual variability in neural activity remains insufficiently explored. The emergence of precision MRI18–22 marks a pivotal shift toward individualized neuroscience, moving beyond group-averaged analyses. Alongside technical advancements, this new methodological approach is promising in terms of clarifying uncertainties in functional anatomy. It may also be able to challenge or strengthen existing models, such as the dual-route model, by providing robust supporting evidence from high-resolution, individual-level data, which can reveal activity that may have been obscured in group-averaged analyses.

To our knowledge, precision fMRI has not yet been applied to investigate word processing, thus leaving inter- and intra-individual variability in semantic, orthographic, and phonological processing largely unexplored. To address this, we present a dataset specifically designed to capture individual differences in word processing, leveraging a precision fMRI approach that combines multi-echo acquisition with multiple sessions per subject. This dense sampling strategy improves data quality and statistical power at the individual level, enabling fine-grained analyses. Multi-echo fMRI enhances temporal signal-to-noise ratio, reduces motion artifacts, and minimizes signal dropouts —particularly in susceptibility prone regions such as the orbitofrontal and inferior temporal cortices.23–26 Advanced denoising techniques like multi-echo independent component analysis (ME-ICA) further improve data quality without compromising the BOLD signal,27 supporting robust and reliable investigation of individual neural activity.

Although not studied using a precision fMRI approach, individual variability has been indirectly explored through subgroup comparisons. For example, higher language ability has been linked to more efficient neural processing and reduced activation,28,29 while complex tasks increase neural engagement. The dynamic spillover hypothesis posits that the right hemisphere supports the left when cognitive demands exceed capacity.28,29 Additionally, males typically exhibit more left-lateralized activity, whereas females show more bilateral activation.30 Despite this, females often outperform males in language tasks,31 challenging the dynamic spillover hypothesis. Moreover, language-related disorders such as dyslexia and speech production deficits are more common in males.31–33 While these findings suggest meaningful sources of variability, they rely on categorical groupings rather than capturing the full spectrum of individual differences — highlighting the value of precision fMRI approaches.

A promising example for applying precision fMRI in language research comes from Fedorenko et al.34 who examined intra- and inter-individual differences in sentence and non-word reading across four subjects. Despite considerable between-subject variability, two individuals tested years apart showed no major intrasubject changes in their language networks. While this small exploratory study illustrates the potential of precision approaches, its limited sample and data quality may have missed key effects. To draw reliable conclusions, a larger sample and a more tailored study design are needed. Another example is the investigation of the language (LANG) network using functional connectivity at the individual level.35,36 These studies revealed that the LANG network includes not only classical language-related regions — such as the IFG, posterior superior temporal cortex (pSTC), posterior superior frontal gyrus (pSFG), temporoparietal junction (TP) and posterior middle frontal gyrus (pMFG) – but also several less typical areas not traditionally associated with language processing, such as the dorsal premotor cortex (dPMC), pSTC, midcingulate cortex (MCC), anterior inferior temporal cortex (aITC), anterior SFG, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Although the network is primarily left-lateralized, homologous regions in the right hemisphere were also identified, albeit smaller in spatial extent. Additionally, the degree of lateralization varied substantially across individuals. The LANG network was found to be in close spatial proximity to other task-related networks, yet it remained functionally dissociable from them. Drawing these distinctions has often proven difficult in previous research, likely because group-level analyses tend to blur the boundaries between adjacent networks.

In the broader field of language fMRI research, many publicly available datasets include naturalistic auditory stimuli (e.g.,37–40). For example, the Narratives41 collection features spoken stories designed to capture continuous, real-world language processing or the collections around the Le Petit Prince narration.42,43 In contrast, event-related designs — such as the one used in this dataset — prioritize experimental control, allowing researchers to isolate neural responses to specific linguistic features. Together, these complementary approaches offer different perspectives on the neural mechanisms underlying language processing. Deniz et al.44 even investigated the effect of the different approaches. Fewer shared datasets focus on visually presented language. Notable examples include the Reading Brain Project L1 Adults,45 which combines reading tasks with eye-tracking, and the Comparing Language Lateralisation Using fMRI and fTCD dataset,46 which includes two visual and one auditory task. Both contain only a single MRI session per participant. Beyond individual datasets, a persistent challenge in open fMRI resources is the variability of metadata quality, often limiting discoverability and reuse. Despite the increasing availability of language-related fMRI data, our search on OpenNeuro found no datasets using multi-echo fMRI in this domain. Queries combining “MRI” and “language” with “multi-echo” or “precision” yielded no results.

The ANC language study dataset was created by the Austrian NeuroCloud47 as a test and showcase dataset. This dense, multi-session fMRI dataset is specifically designed to support investigations into individual variability in word processing, addressing a critical gap in the field: the lack of openly accessible precision fMRI data on semantic, phonological, and orthographic processing. There are multiple approaches to studying functional anatomy with MRI, and our aim was to provide a combination of different modalities to enable comprehensive research on individual variability and word processing. Nevertheless, our primary focus is on task-based functional MRI, which makes up a major part of the dataset. We included two runs of visual and two runs of auditory word discrimination tasks in every session. To complement this, we included a classic resting-state scan with a fixation cross in every session. We also enriched the resting-state component with naturalistic viewing tasks acquired in one session (ses-mov). Having both types of resting-state fMRI in a single dataset allows comparisons between the two and offers options tailored to specific research needs. Additionally, we provide diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and multiparameter mapping (MPM) to support further structural and microstructural analyses. Although the MPM data is not yet supported within the ANC, it will be added once integration is possible. The high-resolution anatomical scans included in each session also support detailed analyses of individual structural variability, such as cortical morphology or regional volume differences. All data are structured according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS)48 and enriched with standardized metadata, including Hierarchical Event Descriptors (HED),49 ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and ease of reuse.

Overall, we aimed to offer a versatile dataset that allows for the study of individual variability in word processing from multiple angles while also supporting a broad range of other research applications. Beyond its scientific value, the dataset demonstrates how precision fMRI can be implemented effectively in smaller research settings and offers a practical model for future studies. Within this paper, we describe the dataset in detail, including the study design, stimuli, task procedures, phenotypic data, data quality, and preliminary results.

Methods

Participants

During subject recruitment we aimed for healthy participants between the ages of 18 and 50, native German speakers, right-handed, with no neurological or psychological disorders. Recruitment was carried out through the personal network of the researchers conducting the study, as well as through internal university platforms and invitations. Subjects were rewarded with lecture credits or a small cash allowance of 80€ after all four sessions.

The experiment is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Salzburg.

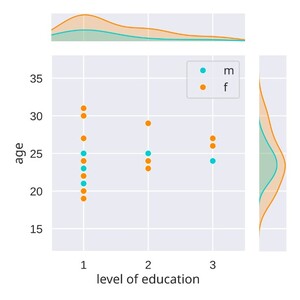

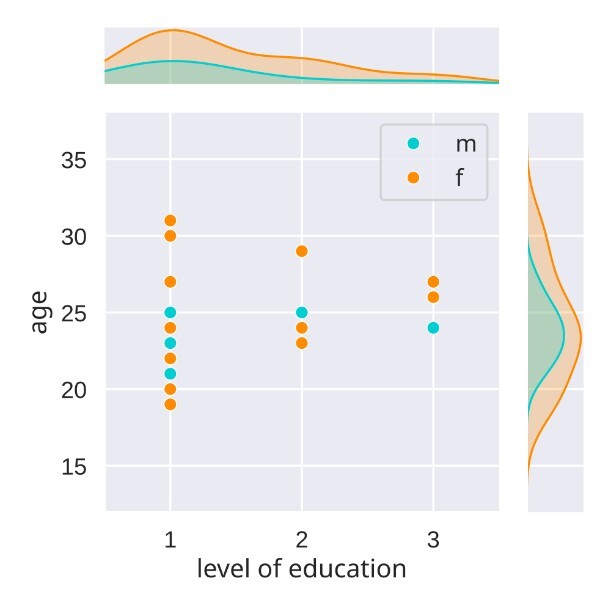

Finally, the ANC language study contains 28 subjects, whereby only 23 completed all four sessions. The age of the sample ranges from 19 years to 31 years with a mean of 23.9 years (SD=3.13), 20 are female and 8 are male. All participants had completed a minimum of secondary education (Alevels), reflecting a typical student sample (see Figure 1).

Experimental Tasks

Our dataset includes five experimental tasks, with a primary focus on assessing different aspects of word processing. To investigate semantic, phonological, and orthographic processing of single words in both modalities (visual and auditory), we implemented word discrimination tasks. In addition to these language-related tasks, we included a resting condition and two naturalistic movie-viewing tasks.

The experiment script as well as connected files can be found in our Open Science Framework (OSF) repository “The ANC language study”.50

Word discrimination tasks

This experimental design employs semantic, phonological, and orthographic discrimination tasks across visual and auditory modalities to dissociate the core components of word processing. The semantic categorization and rhyme judgment tasks are based on and comparable to paradigms widely used in functional neuroimaging studies on word processing,51–53 selected for their ability to selectively engage the regions involved in semantic and phonological processing, respectively. We tailored these tasks to enable the presentation (and potentially analysis) of single words on the screen in each trial and to be suitable for the large number of epochs used in this precision fMRI study. The orthographic discrimination condition contrasts used misspelling detection, which requires a focus on lexical orthographic processing and representations54 and mimics this focus in the auditory condition by using letter judgment task.6 To identify circuits for visual and auditory word processing we also included a visual and an auditory control condition using pseudo-letters in the visual and reversed speech in the auditory condition, which should control for general perceptual and cognitive demands. This cross-modal approach, combining validated tasks with rigorous controls, provides a powerful framework for mapping the brain’s word processing circuit and understanding how orthographic, semantic and phonological word processing engages these circuits.

To implement the task framework described above, each session comprised two runs in the visual modality and two runs in the auditory modality, each lasting approximately 14.5 minutes. Runs were organized in blocks corresponding to the different discrimination tasks, with no more than two blocks of the same type presented in succession. Blocks began with a written instruction (duration=3s), followed by 10 single words, with one or two target words per block (average 1.5 targets). Participants were instructed to press a button as quickly and accurately as possible in response to the target words. During the visual trials, words were presented for 0.5s each, with a fixation cross displayed in between for 1.7 to 3.3s (mean=2.5s). In the auditory runs, a fixation cross remained on the screen between the instructions, while participants listened to ten audio files with short breaks in between. Each audio file contained either a single word or a pure tone from the control condition. At the end of each block, a fixation cross was presented for 4 to 16s (mean=8s). See Figure 2 for a sketch of the visual and auditory discrimination tasks.

The word discrimination tasks were implemented in Python using the PsychoPy (v2023.1.0) library55 enhanced with the psychopy-bids plugin (v 2023.1.1).56

Rest Task

In the resting condition, a black fixation cross was displayed at the centre of a white screen. Participants were instructed to maintain their gaze on the cross, think of nothing in particular, and let their minds wander.

Movie-Viewing Tasks

In addition to the language and rest tasks, participants viewed two different movie stimuli. Both movies were presented using the Presentation® software (Version 22.01 03.21.21)57 and before the start of each movie, a black screen was presented for 10s.

The task moviepc involved viewing the short, animated film Partly Cloudy (5.6min, PIXAR).58 This film has been used as a localizer task for Theory of Mind (ToM) and pain-related neural networks59 as well as to examine developmental changes in these networks.60

The task moviehcp1 consisted of a movie taken from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) (Movie 1 from the 1200 subject release (https://www.humanconnectome.org/study/hcp-young-adult/article/announcing-1200-subject-data-release). It is a combination of five clips from independent films with short rest periods in between (see also Finn and Bandettini61 for a description). The condition was added as a naturalistic viewing paradigm (i.e. an alternative approach to the traditional resting state condition presenting a fixation cross).

Stimuli

All word discrimination tasks used German nouns. The words presented in the semantic, phonological, and orthographic discrimination tasks (except the target stimuli) were selected from the Berlin Affective Word List Reloaded.62 The BAWL-R contains 2900 German words along with basic psycholinguistic properties, like frequency and orthographic neighbours as well as emotional valence, arousal and imageability ratings. To provide discrete emotion information for these words in addition to valence and arousal information from the BAWL-R, we have added the discrete emotion ratings from the Discrete Emotion Norms for Nouns (DENN-BAWL).63 The DENN-BAWL contains 1958 4- to 8-letter German nouns taken from the BAWLR, along with the intensity ratings for the five basic emotions of anger, disgust, fear, happiness, and sadness. Furthermore, we have added additional measures from other (psycho-)linguistic databases, such as the dlexdb64 and subtlex65 including Google Books measures. This results in 1020 stimuli divided into three stimuli sets of 340 stimuli to be presented in semantic, phonological, and orthographic discrimination tasks and matched for: number of letters, number of phonemes, number of syllables, mean bigram frequency, number of neighbours, word frequency, orthographic and phonological Levenstein distance, familiarity, valence, arousal, imageability, anger, disgust, fear, happiness, and sadness, compared in Table 1. The allocation of the three stimulus sets to the three discrimination conditions was randomized across subjects. In addition to the 1020 non-target stimuli, 240 targets per modality were created, with the targets for the semantic and phonological conditions being the same for both modalities.

All stimuli as well as their psycholinguistic measurements can be found in our OSF repository.50

Stimulus Presentation Hardware

Across all tasks, visual stimuli were presented using a BOLDscreen 32 LCD (Cambridge Research Systems, 32 Zoll [16:9], 1920×1080 resolution, 120 Hz), viewed via a mirror mounted on the head coil. The distance between the screen and the mirror was approximately 190 cm. Auditory stimuli were presented using BOLDfonic MRI-compatible headphones (Cambridge Research Systems, UK), which use electrodynamic drivers and provide passive acoustic noise attenuation.

Measurements

Cognitive measures

Reading performance was measured using the Salzburger Lesescreening (SLS)66 and the Salzburger Lese- und Rechtschreibtest II (SLRT II, oral reading task only).67 In addition, four subtests (Vocabulary, Matrix Reasoning, Coding and Digit Span) of the German version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS IV)68 were administered to allow an estimate of general cognitive ability.

Psychopathology screening

The Adult Self Report (ASR)69 was used to screen general mental health.

Scan assessment

Prior to each scanning session, a state assessment is completed to measure differences in mood, stress, sleep, and habits between sessions. The general structure and content of this assessment is based on Russell Poldrack’s assessment data from the MyConnectome project.70 Mood is measured using the German version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS),71 and stress using a variation of the short form of the German adaptation of the Perceived Stress Scale 10 (PSS10).72,73 The sleep section of the assessment asks about sleep duration as well as sleep quality on the previous night, usual sleep duration and current tiredness — based on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.74 Information on alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, and drug use in the past week was also collected.

Procedure

The study consisted of four scanning sessions, each lasting approximately 1.5 hours. Whenever possible, appointments were scheduled weekly, with efforts made to avoid breaks longer than two weeks. On average, sessions were 9.7 days apart (min=2, max=32, SD=5.45). Each session began with the scan assessment questionnaire, followed by the MRI protocol. Starting from the second session, two additional phenotypic tests were administered subsequently. Typically, reading tests were conducted in the second session, the WAIS vocabulary and WAIS coding subtests in the third, and the WAIS matrix reasoning and WAIS digit span subtests in the fourth. The ASR was completed as an online questionnaire at home.

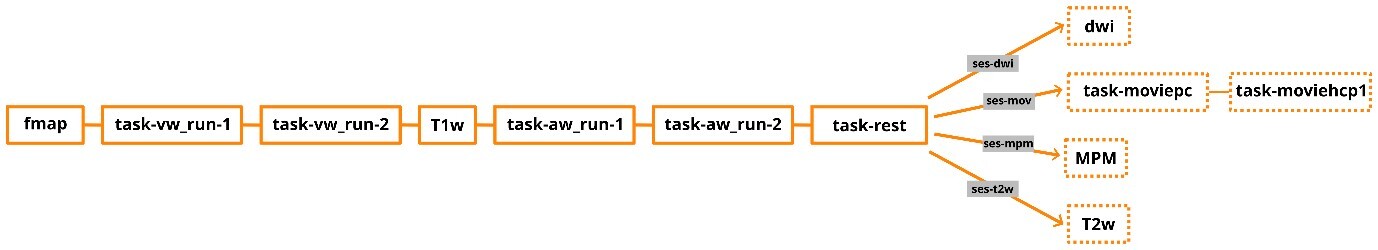

MRI Protocol

The MRI data were acquired using a 3 Tesla Siemens Prisma-fit MRI (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) located at the Christian Doppler University Hospital in Salzburg, Austria. A 20-channel head coil was used. Each session lasted approximately 1.5 hours and started every time with the same course of sequences: a gradient echo field map (TR=623ms, TE1=4.92ms, TE2=7.38ms, voxel size=2.5×2.5×2.5mm), two runs of the visual word discrimination task (task-vw), a high-resolution anatomical T1-weighted (T1w) MP-RAGE scan (TR=2400ms, TE=2.24ms, flip angle=8°, TI=1060ms, voxel size=0.8×0.8×0.8mm, iPAT factor=2 [GRAPPA]), two runs of the auditory discrimination task (task-aw) and the resting-state task (see Figure 3). Functional MRI data sensitive to BOLD contrast were collected during all tasks using T2*-weighted gradient multi-echo axial EPI sequences with four echoes (TR=1299ms, TE1=12.40ms, TE2=30.13ms, TE3=47.86ms, TE4=65.59ms, matrix=78×78, FOV=192mm, flip angle=77°, number of slices=56, voxel size=2.5×2.5×2.5mm, MB factor=4, iPAT factor=2 [GRAPPA]).

At the end of each session, additional MRI data were collected, with each session including one of the following: two video tasks with equal scan sequences to the other tasks, a T2-weighted (T2w) SPACE sequence (TR=3200ms, TE=564ms, voxel size=0.8x0.8x0.8mm, iPAT factor=2 [GRAPPA]) MPM or a high-quality diffusion-weighted image. Sessions were labelled based on the specific additional sequences acquired (ses-dwi, ses-mpm, ses-mov, ses-t2w). The order of the sessions was randomized between the subjects.

The MPM data are not yet included in the data repository, as currently the ANC47 infrastructure does not support this format, but they will be made available as soon as feasible. Its acquisition is based on three multi-echo 3D FLASH sequences,75 with magnetization transfer weighted (MTw), T1w, and proton density weighted (PDw) contrast. All three sequences had a voxel size=1.0x1.0x1.0mm, 8 echos (TEmin=2.46, TEmax=19.68ms), FoV phase=87.5%, slice resolution=91%, slice partial Fourier of 6/8, and a bandwidth of 480Hz/Px. The MTw contrast had a TR=42ms and a flip angle of 7°, the T1w contrast had a TR=23ms and a flip angle of 28°, and the PDw contrast had a TR=23ms and a flip angle of 5°. To correct for spatial variations in receive coil sensitivity (B1-), separate receive coil sensitivity maps (RB1COR) were acquired for the head and body coils for each MPM contrast (PDw, T1w, MTw). These RB1COR maps were obtained with voxel size 4.0×4.0×4.0mm, TR=3.8ms, TE=1.71ms, flip angle 6°, Fov phase=87.5%, and bandwidth = 480 Hz/Px. A single transmit radiofrequency field map (TB1RFM) was acquired using the vendor supplied B1 mapping sequence to correct for transmit field (B1+) inhomogeneities across all MPM sequences. This map was collected with voxel size 4.0×4.0×5.0mm, TR=2000ms, TE1=14ms, TE2=14ms, and multiple flip angles of 90°, 120°, 60°, 135°, and 45°.

The diffusion image was modelled after the recommended sequence of the DSI Studio software76 with a voxel size of 2.0x2.0x2.0mm, TR of 2490ms, TE of 99.20ms, 72 slices, 256 diffusion directions and a max b-value of 4000. The sequence is accompanied by two EPI field maps in opposite phase encoding directions (phase encoding direction=AP/PA, voxel size=2.0x2.0x2.0mm, TR=2490ms, TE=99.20ms, 72 slices, 6 diffusion directions, MB factor=4).

The dataset repository also includes the original scanner protocol documentation, providing detailed acquisition parameters for all sequences used in the study.

Data Management, Sharing, and Analysis

The dataset is stored within the Austrian NeuroCloud (ANC).47 The ANC is an actively curated repository powered by GitLab for FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable)77 neurocognitive research data. It exclusively accepts datasets structured according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard,48 with compliance validated automatically within the repository. Further, data stewards help to maintain the desired metadata standard. Metadata for every dataset is publicly available through a dedicated dataset webpage (for this dataset: https://bids-datasets.datapages.anc.plus.ac.at/neurocog/anclang/), ensuring transparency and discoverability. Each dataset is also assigned a persistent Digital Object Identifier (DOI; for this data set 10.60817/39tp-6031), guaranteeing long-term accessibility and citation.

BIDS compliance of the ANC language study was checked by an automated pipeline within the ANC, which uses bids-validator version 2.0.2, with default BIDS schema version 1.0.1 and implements version 1.10.0 of the BIDS specification. The dataset contains all phenotypic data, the raw MRI data, the event data, and all required meta files. Additionally, in the source data a document exported from the scanner containing details about the sequences’ parameters was added. All functional MRI runs had the first 6 volumes (dummy scans) removed to exclude non-steady-state signals and ensure signal stability. The ReadMe file provides further description of the data as well as tables containing information about any issues during data acquisition, such as missing data for a subject. It is also publicly viewable on the dataset’s website.

We further annotated the event data using Hierarchical Event Descriptors (HED)49 providing a well-defined vocabulary that is both human- and machine-readable and through the HED LANG extension78 also suitable for language research. This facilitates precise event annotation, supports cross-dataset analyses, and even enables dataset discovery based on specific task or event characteristics. This feature gains special importance as the ANC is connected to NeuroBagel,79 which enables dataset discovery via a search tool querying multiple data repositories.

Our analysis will focus on understanding both intraindividual and interindividual variability in language processing. Within subjects, we aim to assess the stability of activation patterns across sessions and explore how variability relates to behavioural factors such as mood, stress, and cognitive performance. Between subjects, we will investigate individual differences in neural responses to the word discrimination tasks and how they relate to cognitive and linguistic abilities.

Preprocessing was carried out in four stages. First, data were processed with fMRIPrep (version 24.1.1)80 using the multi-echo option to ensure that the preprocessed single-echo time series were retained. Second, denoising and optimal combination of the echoes were performed using tedana (version 25.0.1).81–83 In tedana, multi-echo images were first combined using voxel-wise T2w averaging to reduce signal dropout and enhance BOLD sensitivity. It further uses principal component analysis (PCA) and independent component analysis (ICA) to identify and remove non-BOLD components before optimally combining the time series. Finally, the denoised and optimally combined images were spatially normalized to MNI standard space using Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) (version v2.6.3).84 At last the images were smoothed using SPM1290 in a MATLAB environment (version 8.1.0.604 [R2013a[).85 We then performed a first-level general linear model (GLM) analysis in SPM12, contrasting all discrimination tasks (semantic, orthographic, and phonological) against the false font condition to compare neural activity during word processing versus during the processing of visually similar, non-linguistic stimuli.86 We further conducted a second-level group analysis in SPM12 using a one-sample t-test across all participants who completed all four sessions (excluding sub-s0016 and sub-s018 due to technical issues).

FAIR assessment

To test the general FAIRness of the dataset we used the F-UJI tool (software version 3.5.0, metrics_v0.8).87 Our dataset reached overall a level of advanced FAIRness, with a score of 84% (see Figure 4). Please note that domain-specific data requirements and standards, such as BIDS and, thus, their fulfillment are not yet integrated in the F-UJI tool for neuroscientific data. However, a score above 50% can already be seen as acceptable.

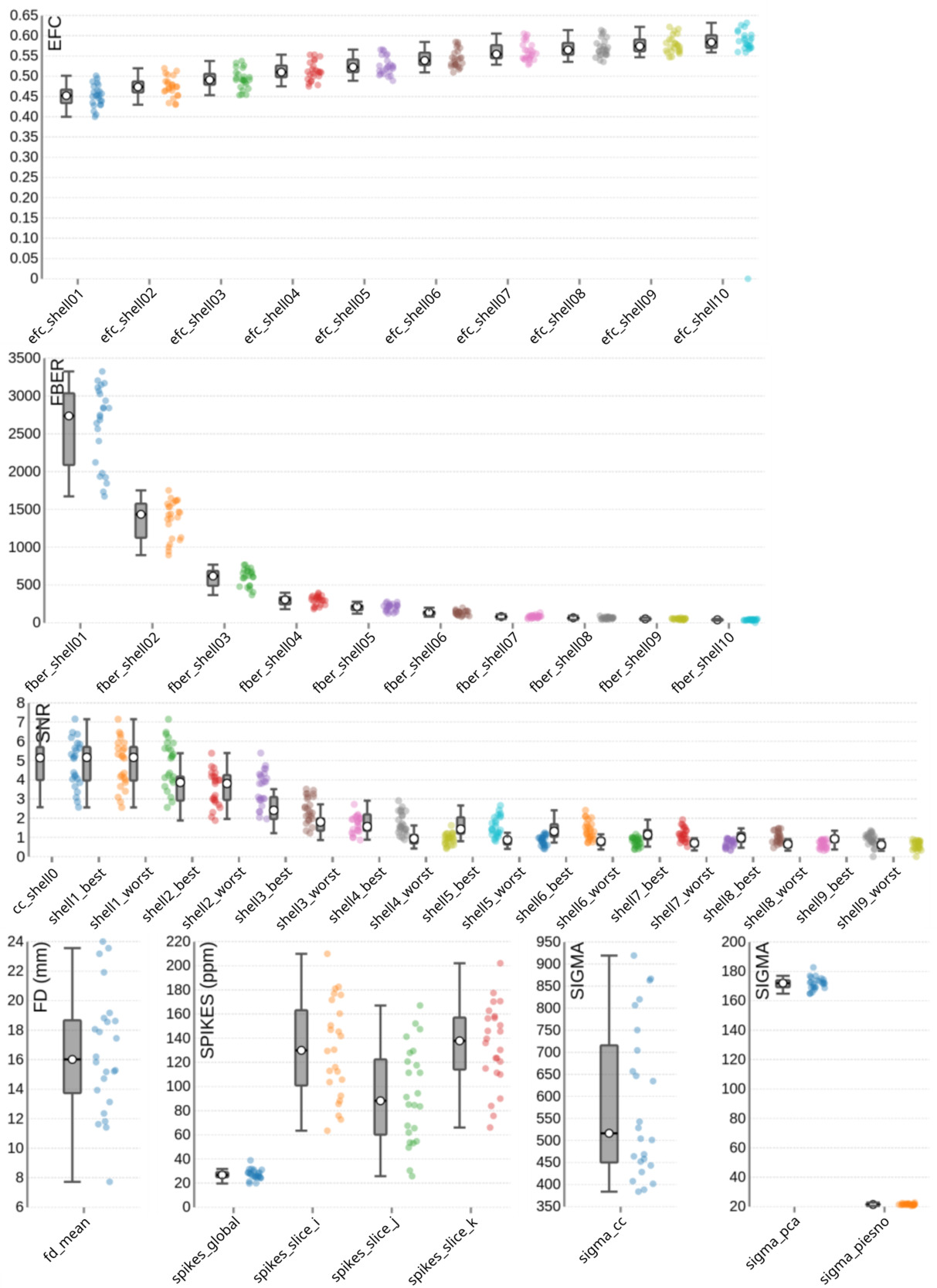

MRI Data Quality Assessment

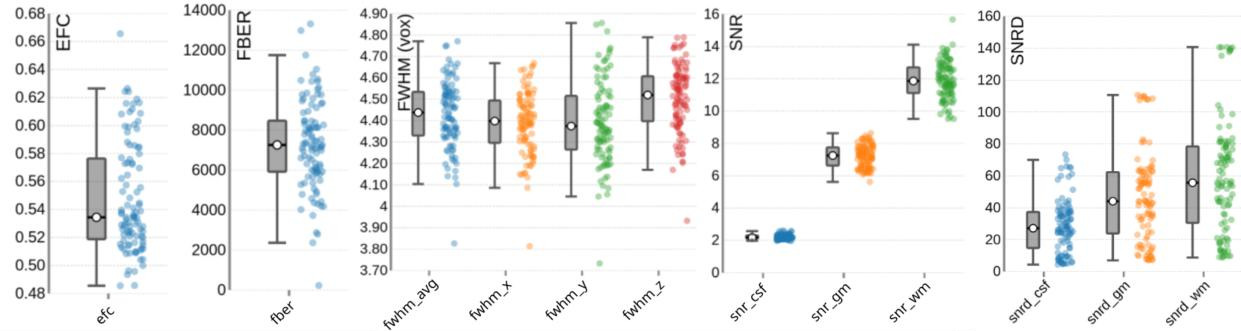

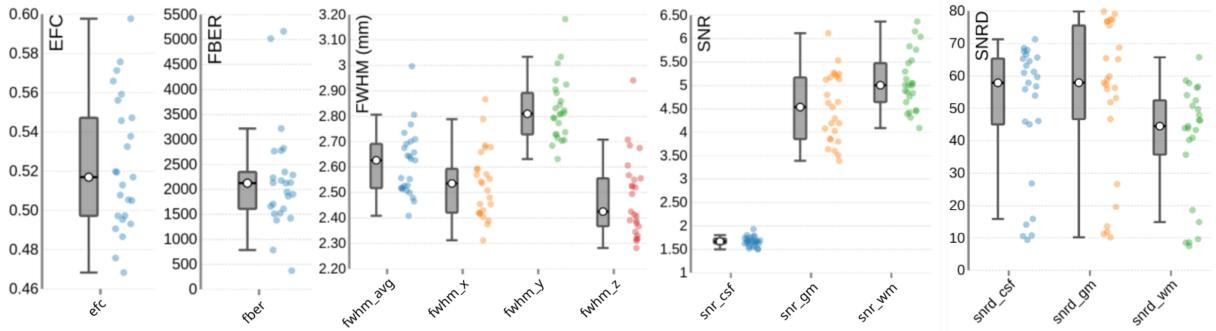

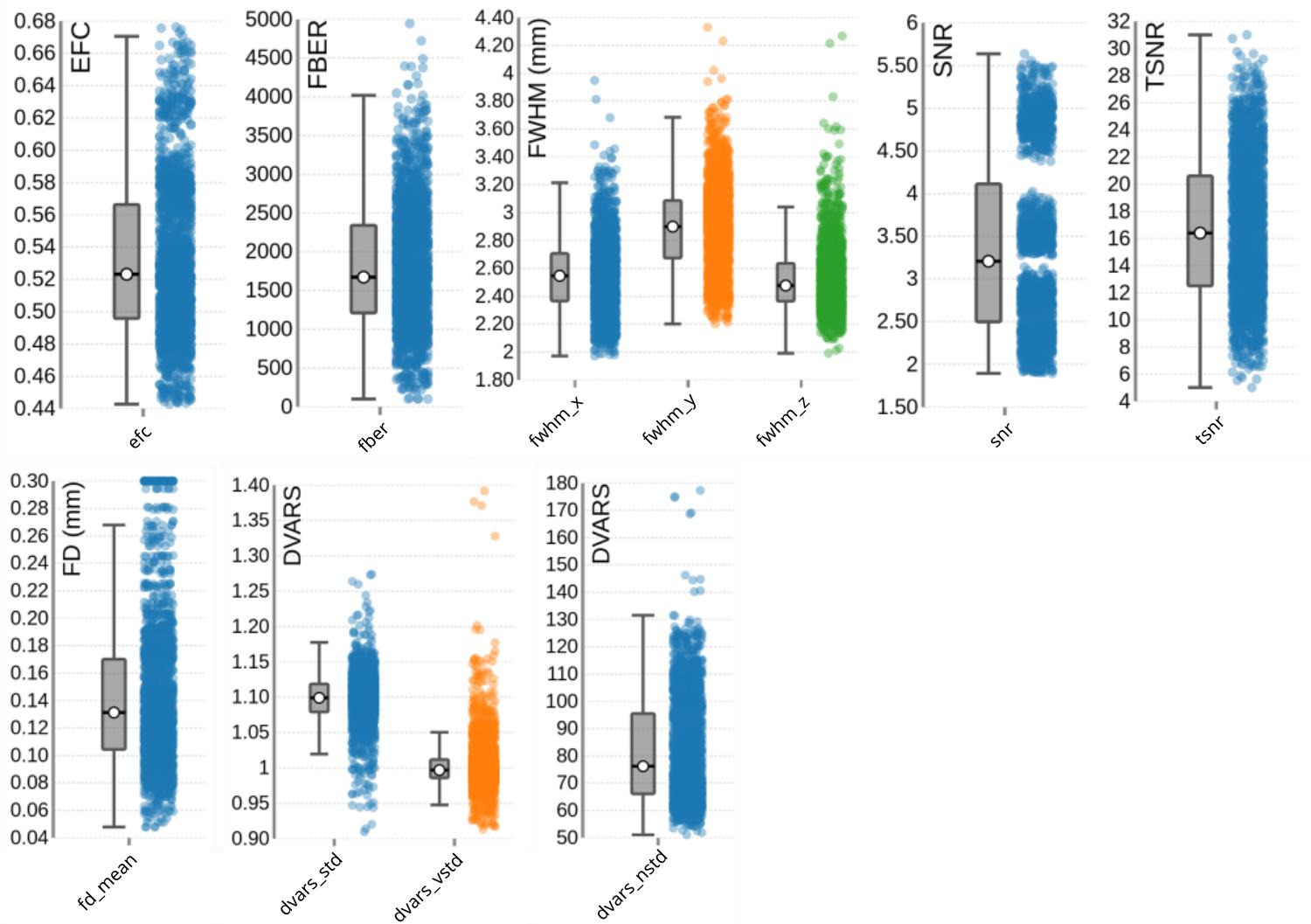

To assess data quality the MRI Quality Control tool (MRIQC)88 (version 24.0.2) was executed on the raw, unpreprocessed data at both: the group and subject level. Selected parameters for the anatomical, functional, and diffusion data for the group level quality assessment are displayed in Figure 5 to 8 and discussed separately for each modality below. The complete output of the MRIQC assessment on the group level as well as on the single subject level can be found in our OSF repository of the dataset.50 For more information regarding the different quality metrices please refer to the MRIQC documentation (https://mriqc.readthedocs.io/en/latest/measures.html).

T1-weigthed (T1w) images

Figure 5 presents the group-level image quality metrics for all T1w images with four images per subject (one per session). Entropy Focus Criterion (EFC), where lower values indicate less head motion and image blurring, has a group median of 0.53, with a notable outlier observed for sub-s021_ses-mpm, suggesting potential motion or artifact in that scan. Foreground-Background Energy Ratio (FBER), which is preferable at higher values since it reflects stronger tissue contrast relative to background noise, shows a group median of 7258.21, with sub-s021_ses-mpm again standing out as an outlier due to its low value. Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM), an indicator of image smoothness where lower values imply a sharper image, has a group median of 4.44. MRIQC provides two different approaches for the calculation of the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in structural images: within the brain mask (labelled as SNR) and Dietrich’s SNR taking the noise outside the brain as reference (labelled as SNRD). For the SNR the group medians are 2.18 for cerebrospinal fluid (snr_csf), 7.25 for grey matter (snr_gm), and 11.86 for white matter (snr_wm). For the SNRD the group medians are 27.11 for cerebrospinal fluid (snrd_csf), 44.02 for grey matter (snrd_gm), and 55.63 for white matter (snrd_wm).

T2-weighted (T2w) images

One T2w image was acquired per subject. The image quality metrics on the group level for the T2w images are summarized in Figure 6. The EFC has a group median of 0.52. The FBER shows a group median of 2124.77. However, sub-s001 is a visible outlier with a notably low FBER, suggesting lower contrast in that image. FWHM has a group median of 2.63, with sub-s001 again appearing as an outlier due to elevated FWHM values. The SNR shows a group median of 1.67 for cerebrospinal fluid (snr_csf), 4.54 for grey matter (snr_gm), and 5.00 for white matter (snr_wm). The SNRD has a group median of 57.85 for cerebrospinal fluid (snrd_csf), 57.89 for grey matter (snrd_gm), and 44.48 for white matter (snrd_wm).

Functional (BOLD) images

For the functional scans (BOLD fMRI), MRIQC was performed on the group level on the raw data using the single uncombined echo files of all subjects, all sessions, all tasks (including rest) and all runs. Thus, each data point in Figure 7, which summarizes the image quality metrics for the functional MRI acquisitions, represents a single uncombined echo file. The EFC has a group median of 0.52. The FBER shows a group median of 1672.71. The FWHM reveals group medians of 2.55 for the x-direction (most extreme outliers for sub-s014_ses-t2w_task-vw_run-1, sub-s001_ses-mpm_taskvw_run-1, sub-s019_ses-mpm_task-rest), 2.90 for the y-direction (most extreme outliers for: sub-s014_ses-t2w_task-vw_run-1, sub-s006_ses-t2w_task-aw_run-2, subs019_ses-mpm_task-vw_run-2), and 2.48 for the z-direction (most extreme outliers for sub-s014_ses-t2w_task-vw_run-1, sub-s001_ses-mpm_task-vw_run-1, sub-s012_sest2w_task-aw_run-2).

The SNR for the functional images was calculated within the brain mask and had a group median of 4.11. However, as the SNR is TE-dependent, differences23,81,89,90 between different echoes can be observed. This explains the wide variation across echoes: echo 1 showed the highest SNR with a median of 4.88 (ranging from 4.4 to 5.64), followed by echo 2 with a median of 3.56 (ranging from 4.0 to 3.3), which is closest to a typical TE used in single-echo fMRI acquisitions.89 Echo 3 and echo 4 had progressively lower SNRs, with a median of 2.81 and 2.26 ranging from 3.14 to 2.5 and 2.5 to 1.89, respectively, consistent with greater signal decay at longer TEs. These echo-dependent differences are expected and are appropriately handled during preprocessing through optimally weighted combination of the echoes.81,82 Notably, in Figure 7, these echo-specific TE-dependent differences between the echoes are also visible, as the echoes form distinct clusters (“blobs”) of data points, illustrating the systematic variation in SNR across TEs.

The temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR), which reflects signal stability over time, has a group median of 16.40 (min=5.02, max=31.01; see Figure 7). Even when calculated for the unpreprocessed data, the tSNR values appeared to be relatively low at first glance, compared to other tSNR values commonly reported in multi-echo dataset.89,90 To evaluate whether this reflects data quality issues or acquisition-related sequence characteristics, we compared our values with the tSNR of a publicly available dataset on OpenNeuro (ds005250)91 that closely matched our acquisition parameters (multiband acceleration, GRAPPA, relatively short TR, and small voxel size). As the tSNR values of this reference dataset were similar to those observed in ours (median=17.14, min=5.09, max=35.99) this suggests that the moderate tSNR is typical for acquisitions using relatively small voxel sizes together with multiband and GRAPPA acceleration. Importantly, after preprocessing, the tSNR substantially improved (median = 45.4).

Head motion is relatively low across the dataset, with a group median Framewise Displacement (FD) of 0.13 mm. Spatial standard deviation of successive difference images (DVARS), a measure of signal variability between volumes and a marker for motion-related artifacts, shows a group median of 1.10 for the standardized version (dvars_std), with most extreme outlier in sub-s005_ses-mpm_task-aw_run-1 and subs016_ses-t2w_task-aw_run-2. The voxel-wise standardized version (dvars_vstd) has a median of 1.00, again with sub-s005_ses-mpm_task-aw_run-1 as a notable outlier. For the non-standardized DVARS (dvars_nstd), the group median is 76.22, with clear outliers across all tasks for sub-s021_ses-mpm.

Diffusion-weighted (DWI) images

Image quality metrics for the DWI data are summarized in Figure 8. The EFC shows shell-specific medians ranging from 0.45 to 0.58, consistent with increasing artifact susceptibility at higher diffusion weightings. FBER ranged across shells from 2735.83 in lower b-value images to 39.84 at higher b-values – a pattern expected due to signal attenuation with increasing diffusion weighting. The SNR also declines with b-value, with median values ranging from 5.17 to 0.61 across shells, and 5.14 specifically within the corpus callosum (snr_cc). Head motion, assessed via FD, shows a group median of 16.2 mm. Spike artifacts has a group median of 26.75 parts per million (spikes_global), with lower values indicating fewer transient disruptions. Noise estimation metrics also reflected shell-specific degradation, with group medians of 516.32 for sigma_cc, 171.97 for sigma_pca, and 21.46 for sigma_piesno.

Results

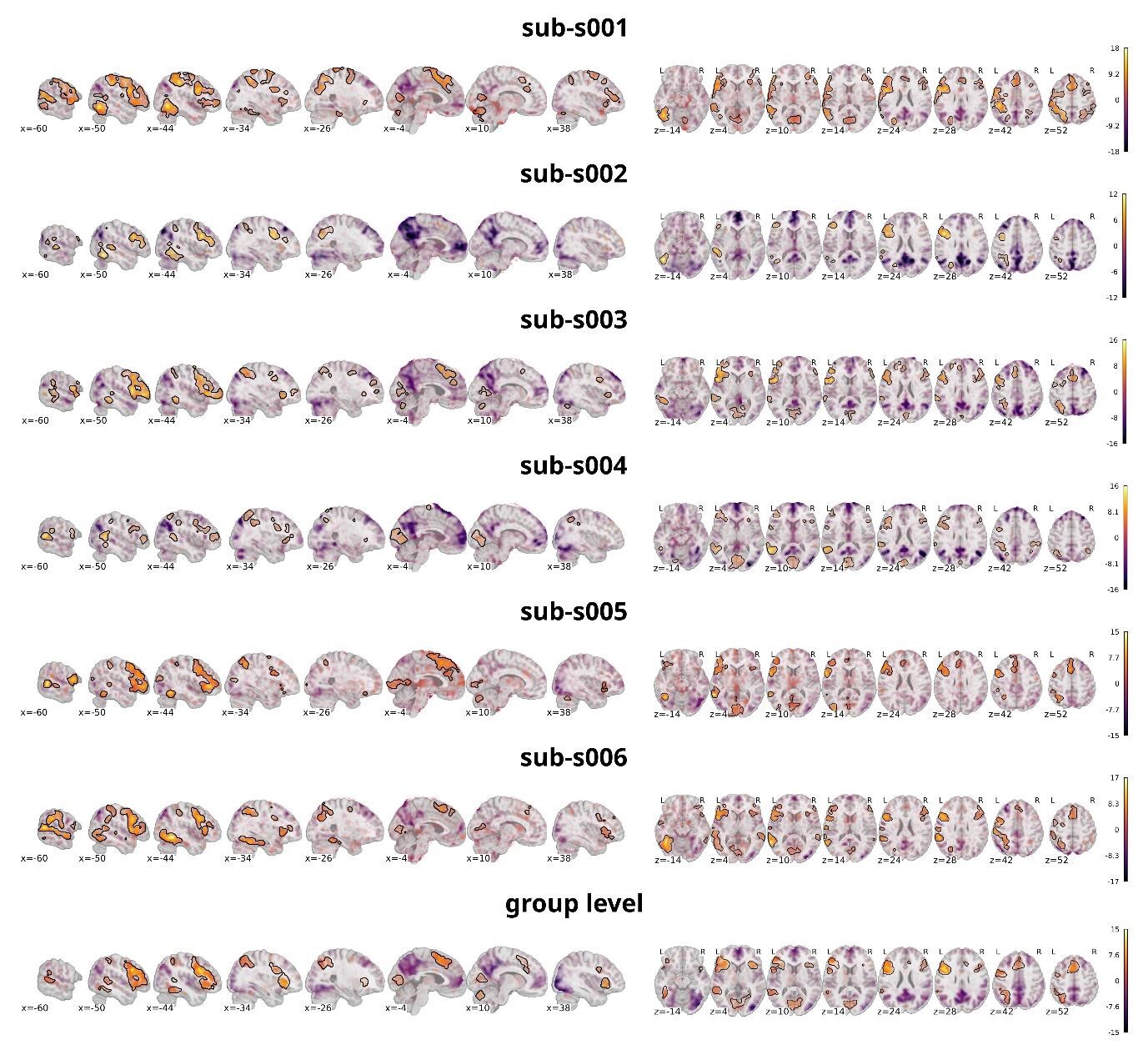

The goal of this section is not to provide definitive scientific findings, but rather to illustrate the kinds of insights the dataset can support. These demonstrations are intentionally limited in scope: they are meant to showcase data quality and usability, not to serve as a substitute for the comprehensive statistical analyses that future research may pursue. To that end, we focused exclusively on the visual modality, combining data from four sessions per subject, each comprising two runs of tasks.

The analysis targeted the same contrast as on the individual level, comparing all discrimination tasks against the false-font condition. Figure 9 shows the statistical activation maps with transparent thresholding for six individual participants (sub-s001 to sub-s006) overlaid on the individual T1w images as well as the activation map on the group level overlaid on a template provided by nilearn.86 Significant clusters (p<0.001 uncorrected, cluster extent thresholds k=100 voxels) are outlined in black. For figure creation the nilearn toolbox86 within a python92 environment was used.

Neural activation was predominantly left-lateralized, including the vOT, IFG, and lateral temporal areas — consistent with previous findings on word processing, demonstrating that the task reliably engages expected language-related regions. As this is also evident on the single subject level, it shows that the data quality is sufficient to detect meaningful effects without group averaging. This supports the dataset’s utility for future analyses focusing on individual variability and subject-level decoding. Importantly, the individual maps also reveal visible differences between participants. In comparison with the group-level maps both overlap, and divergence is observable. Most regions that reached significance at the group level were also present in most individual participants, underscoring the robustness of these effects. However, some clusters observed in single participants did not appear in the group map, while other regions absent in individual maps emerged at the group level. For instance, sub-s002 did not show significant activation in the right prefrontal cortex, yet this region was reliably present in the group analysis, suggesting that individual differences can be masked in aggregate results. Additionally, regions with no significant activity at the group level often overlapped with similar patterns in individual maps, suggesting consistent engagement even when statistical thresholds were not reached. Taken together, these observations highlight how precision MRI, through dense and reliable sampling, can detect neural activity with greater detail. This makes it possible not only to investigate brain function at the level of individual participants but also to characterize variability between individuals. It is important to note, however, that these are preliminary analyses intended to illustrate the dataset’s potential; more comprehensive statistical evaluations will be necessary to fully substantiate these points, but such analyses fall outside the scope of this dataset description.

Strengths and Limitations

This dataset represents a high-quality resource that significantly contributes to the fields of neuroimaging and language research, particularly in the context of individual variability and precision fMRI.

A key strength of the dataset lies in its high data quality, achieved through multi-echo fMRI. This approach enhances signal reliability and reduces noise — factors especially important when examining subtle, subject-specific neural patterns.23,93 While the sample includes a relatively modest number of participants (n=28), each completed four sessions, contributing two hours of task data per modality (visual and auditory) and one hour of traditional fixation-cross resting-state data. In total, the study generated 161 hours of MRI data. This dense sampling yields exceptionally rich data per subject, making the dataset particularly well-suited for studying intra- and inter-individual variability in brain activity. One limitation, however, is that word processing was assessed using only a single task type — word discrimination — which may limit the breadth of cognitive processes examined. On the other hand, this focused design enabled the collection of extensive data for this specific task, a depth that would not have been feasible had multiple tasks been included.

In designing the study, we aimed not only for depth but also for breadth, creating a multimodal dataset that supports the investigation of word processing from multiple perspectives. Beyond task-based fMRI, the dataset includes two types of resting-state acquisitions: a traditional fixation-cross condition and a naturalistic movie-viewing paradigm. This combination allows for comparisons between different resting-state approaches and supports varied analytic strategies. The dataset is further complemented by detailed anatomical scans (four T1w and one T2w image per subject), DWI, and, once integrated, MPM. Together, these modalities support the analysis of function, structure, and connectivity within a unified dataset. This design was intended to offer flexibility for addressing a range of research questions.

In terms of task design, the dataset includes 1,020 distinct word stimuli, providing high linguistic coverage and reducing stimulus-specific biases to support more reliable generalizations. The use of identical word sets in both auditory and visual modalities enables systematic comparisons between sensory modalities in word processing. It is important to note that the study was conducted in German, a language with a relatively consistent orthography, which may influence phonological and orthographic processing and could limit the generalizability of findings to languages with less consistent spelling-sound correspondences.

Another limitation of the study is the participant pool, which consists mainly of university students. This results in a relatively homogeneous sample in terms of age, education, and language abilities, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the gender distribution is unbalanced, which may influence findings related to sex differences. However, limitations related to the sample can be mitigated by future studies focusing on more diverse populations or by leveraging this dataset as a comparison group or as part of meta-analyses to enhance generalizability.

Reflecting current standards in open science, the dataset was curated in adherence to the FAIR principles77 — findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability — ensuring its lasting value to the research community. The dataset is fully organized according to the BIDS,94 a widely accepted standard that ensures interoperability and compatibility with existing neuroimaging analysis tools. The dataset is accompanied by rich metadata, including HED,95 enabling precise, machine-readable annotation of task events. These features not only improve transparency but also enhance the dataset’s utility for large-scale or automated meta-analytic studies. The dataset is assigned a DOI for persistent accessibility and is hosted on the ANC.47 This comprehensive curation ensures that the dataset remains a reliable, accessible resource for future research, contributing to cumulative scientific progress in the fields of neuroimaging and language.

Conclusion

In summary, this dataset combines high-quality imaging, dense within-subject sampling, and standardized organization, offering a valuable resource for studying individual variability and the neural basis of word processing. Its structure and metadata support reproducibility and facilitate integration with existing neuroimaging tools. By providing a well-curated and accessible dataset, this work contributes to ongoing efforts in precision neuroimaging and lays the groundwork for future research in cognitive neuroscience.

Data Availability Statement

The ANC language study dataset is available through the Austrian NeuroCloud (https://anc.plus.ac.at/)47 at: https://doi.org/10.60817/39tp-6031. The ANC is a research data repository designed for FAIR77 and trustworthy data management in neuroscience. The dataset is assigned a persistent DOI to ensure long-term findability and citation, and metadata are publicly accessible via the DOI landing page.

The dataset contains MRI images from which facial features could be reconstructed. In compliance with the GDPR, data that may carry personal information, such as identifiable facial features, cannot be made publicly available and demand access control. Therefore, access to this dataset is restricted but may be granted upon request. Only requirement to obtain access is the agreement with the ANC terms of use (https://handbook.anc.plus.ac.at/terms/). Please mind that these currently limit access for research purposes only. This special care is required to satisfy European and Austrian data protection laws, for details please refer to the ANC (https://anc.plus.ac.at/). Once access is granted, you will be able to simply download the dataset.

In addition to the dataset repository on the ANC, we also created a repository (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/W7BFA)50 on Open Science Frameworks OSF to provide additional information. This repository contains all stimuli, the experiment scripts and the MRIQC output on the group and subject level. As no data per se is shared within the OSF repository no access restrictions were necessary, and it is publicly available.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Austrian NeuroCloud (ANC) under grant number 2920, funded by the Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF). The authors gratefully acknowledge the data storage infrastructure and organizational support provided by the ANC, as well as the computational resources and services offered by Salzburg Collaborative Computing (SCC), funded by the BMBWF and the State of Salzburg.

We extend our sincere thanks to the ANC team for their dedicated support throughout the project. In particular, we thank Dr. Mateusz Pawlik for his assistance with the development and troubleshooting of code related to MRI data processing and management; Monique Denissen for her contributions to HED tagging and experiment programming; and Bianca Löhnert for her work on implementing randomization procedures in the experimental design.

This research also benefited from the use of the PsychoPy-BIDS plugin,56 which facilitated the integration of our experimental design with BIDS-compatible data formats.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

_the_visual_and_b)_the_auditory_discrimination_tasks.jpg)

_the_visual_and_b)_the_auditory_discrimination_tasks.jpg)