Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most common neuroimaging modality in neuroscientific research, since it is non-invasive and can provide good contrast between cortical gray matter (GMc) and white matter (WM), enabling assessment and quantification of different brain structures and pathologies. Different MRI acquisition protocols and technologies have been developed in the last few decades, increasing our ability to estimate whole brain, GMc and WM volumes,1 volumetric and relaxation changes of specific structures in neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., hippocampal volume changes in dementia),2,3 and lesion occurrence and their longitudinal evolution (e.g., WM hyperintensities in cerebrovascular disease).4 However, to confirm MRI findings, histology remains the gold standard in neuroscientific research since it provides cellular resolution.5,6 Being able to correlate MRI imaging with cellular histology is of utmost importance to establish a meaningful anatomical and pathophysiological conclusion.

Biopsies from living individuals for histopathological study can only provide very small samples and are rarely performed due to their invasive nature. Therefore, researchers commonly use post-mortem tissue samples that are generally provided by brain banks. However, brain banks usually provide limited numbers of small tissue samples, one hemisphere being fixed by immersion in neutral-buffered formalin (NBF), and the other frozen.7,8 Alternatively, neuroscientists could obtain higher numbers of full brains from gross anatomy laboratories that collaborate with body donation programs. These brains are fixed through whole-body perfusion, using solutions other than NBF, which are typically used in brain banks since the body is used for teaching gross anatomy. Our team’s previous work has shown that two solutions used in our human anatomy laboratory, a saturated-salt solution (SSS) and an alcohol-formaldehyde solution (AFS), preserve antigenicity of the four main cell populations in mice brains9 and in human brain samples.10 This work established that histology of human brain tissue fixed with SSS or AFS is of sufficient quality for neuroscientific research, potentially increasing the amount of brain tissue available to neuroscientists for histological studies. Furthermore, performing MRI scans in these brains is also feasible, enabling correlations with histology findings.11,12

Since MRI is the most common neuroimaging modality, and histology remains the gold standard, registration of images obtained with these two modalities is essential to correlate findings.13–15 Previous work on Alzheimer’s disease,16–21 Parkinson’s disease,22 strokes,23 cerebrovascular diseases,24–27 white matter hyperintensities,28,29 multiple sclerosis,30–33 etc., have used registration between MRI and histology (of tissue fixed with NBF) to either confirm the clinical diagnosis or to elucidate the cellular changes in tissues and lesions that are characteristic of these pathologies.

While both MRI and histology assessments are feasible in tissues fixed by perfusion using neuroanatomy solutions (i.e., AFS and SSS), previous work has not established whether studies that use registration would be feasible and of sufficient quality in these brains. Hence, the goal of the present study was to describe the protocols that are suitable for manual linear registration of the histology sections to MRI in human brain blocks fixed with three solutions (SSS and AFS used in anatomy laboratories, and NBF used in brain banks), and to compare the robustness of the alignments in different histology stains across the fixatives as well as different staining types.

Methods

Population

We used a convenience sample of 12 human brain blocks (SSS: N=4, AFS: N=4, and NBF: N=4) from our body donation program (University of Quebec in Trois-Rivieres, UQTR), that were fixed by whole-body perfusion. The bodies are injected with 25 liters of one of the three fixatives through the right common carotid artery using a pump at 30 pounds per square inch. Prior to death, the donors consented to body donation and sharing their medical information for research or teaching purposes. This study was approved by the University’s Ethic Subcommittee on Anatomical Teaching and Research (UQTR) and by the Douglas Research Centre Ethic Committee (McGill University, Montreal). The mean age at time of death was 81 years old (SD=9.65; range from 64 to 96). Female to male ratio reached 2:1. The mean post-mortem interval (PMI, i.e., delay between death and injection of the fixative solution) was 18.6 hours (SD=8.6; range from 3 to 36). The mean processing delay (PD, i.e., delay between injection of the fixative solution and MRI scans followed by histology procedures) was 32.9 months. The donors’ demographics are reported in Table 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging protocol

Tissue blocks of approximately 3x3x3 cm3 were cut from regions that were macroscopically of good quality (i.e., avoid tears that could have happened during brain extraction and during removal of the arachnoid). One block containing neocortex and subcortical WM was taken from each lobe (i.e., temporal, frontal, parietal and occipital) for each of the fixative groups. Blocks were packed in small containers filled with a high-density fluoropolymer fluid free of MRI signal (Christo-Lube, Engineered Custom Lubricants). To avoid air bubbles, the tissue blocks were packed in the container while fully immersed in a bucket filled with the fluoropolymer fluid, closing the lid while the specimen and container were fully immersed. The blocks were packed so that the flat-cut surface of the block was orientated to the top (i.e., in which the high-density fluid pushed the flat surface consistently to the top of the lid), allowing for a consistent orientation of the high-resolution plane of the MRI acquisition (0.13 x 0.13 mm). Blocks were then scanned in a 7 Tesla Bruker Biospec 70/30 animal MRI scanner at the Douglas Cerebral Imaging Centre (CIC) using a Bruker transmit-receive volume coil with an 86-mm inner diameter. Six high-resolution sequences (T1-FLASH, T2-TurboRARE, T1-map, T2-map, T2*map, and MP2RAGE) were acquired overnight using parameters that were described in the Douglas-Bell Canada Brain Bank Post-mortem brain imaging protocol.34

Histology procedures

Sectioning and mounting

After MRI scans were completed, the tissue blocks were rinsed in 0.1M Phosphate buffer and photographed. The blocks that were too large to fit into the vibratome (Leica VT1000S) were cut and photographed again before cutting into 40 μm sections. The flat surface of the blocks was mounted on the vibratome, allowing for sectioning in the same orientation as the high-resolution plane of the MRI (since the flat surface was lying on top of the lid while scanning, which was used to adjust the field of view for the high-resolution MRI plane, and since we opened the MRI in Display to visually validate the high-resolution plane). Sections of two different levels of the blocks (also photographed), which resulted in parallel levels to the high MRI resolution plane, were selected as followed: five sections per level (ten total) were mounted on 70 x 50 mm slides and processed with five histochemistry (HC) stains. Similarly, two consecutive sections (i.e., from the same level parallel to the high MRI resolution plane) were mounted for immunohistochemistry (IHC) with 4 different antibodies. We selected the level that showed the least amount of deformation and tears to obtain these eight sections. One section per antibody was processed with a heat-induced antigen retrieval (AR) protocol (boiling 20 minutes in 0.01M Citrate Buffer), and the other was processed with IHC directly, to avoid the potential additional tearing and deformation caused by the heat of the AR procedure. This procedure resulted in 18 mounted sections per block.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was used to label the four main cell populations: neurons, using neuronal nuclei (NeuN) antibodies, astrocytes, using glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody, microglia, using ionized binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) antibody and oligodendrocytic myelin using proteolipid protein (PLP) antibody. Procedures were followed as described in Frigon et al., 202410 but sections were processed mounted on the slides rather than free-floating.

Histochemistry stains

We used five HC stains to label the main brain cell populations, avoiding antibodies that require antigen configuration specificity. We used Cresyl Violet (Nissl stain, which labels neurons and glial cell bodies), Luxol Fast Blue (myelin), Prussian blue staining (Perl’s stain, which labels iron deposits), Bielschowsky’s silver staining (which labels axons and neurofibrillary tangles) as previously described in Frigon et al., 2024.10 We also used Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining Kit from Abcam (ab245880) and followed their guidelines.

Imaging

Mounted stained sections were scanned at 40X magnification with an Olympus VS120 Slide scanner at the CIC. The images were converted from .vsi format to .nifti format and downsampled by a factor of 20 to reduce file size to facilitate the registration step using an in-house MATLAB script. The resulting images were converted to minc format to allow the use of the Register software from the MINC Tool-Kit (McConnell Brain Imaging Centre) to perform manual registration.

Registration

The T2-TurboRARE images (voxel resolution of 0.13*0.13*0.5 mm) were used for registration with histology since they provide good anatomical contrast that are close to in vivo images, in comparison to post-mortem T1w images in which the gray level contrast is reversed.34 Registration between histology images and MRIs was performed using a manual linear registration approach (3 rotations, 3 translations, 1 scale), tagging a minimum of 4 landmarks using Register software (included in the MINC Tool-Kit). More fiducial markers (i.e., tags) were placed if necessary, and the required number was considered as a variable of interest (see next section). Since all the acquired post-mortem sequences are co-registered together, histology images could also be co-registered to the other acquired sequences using the same transformations. The same approach was repeated to register the block photos to the MRIs.

Variables of interest

Histology quality

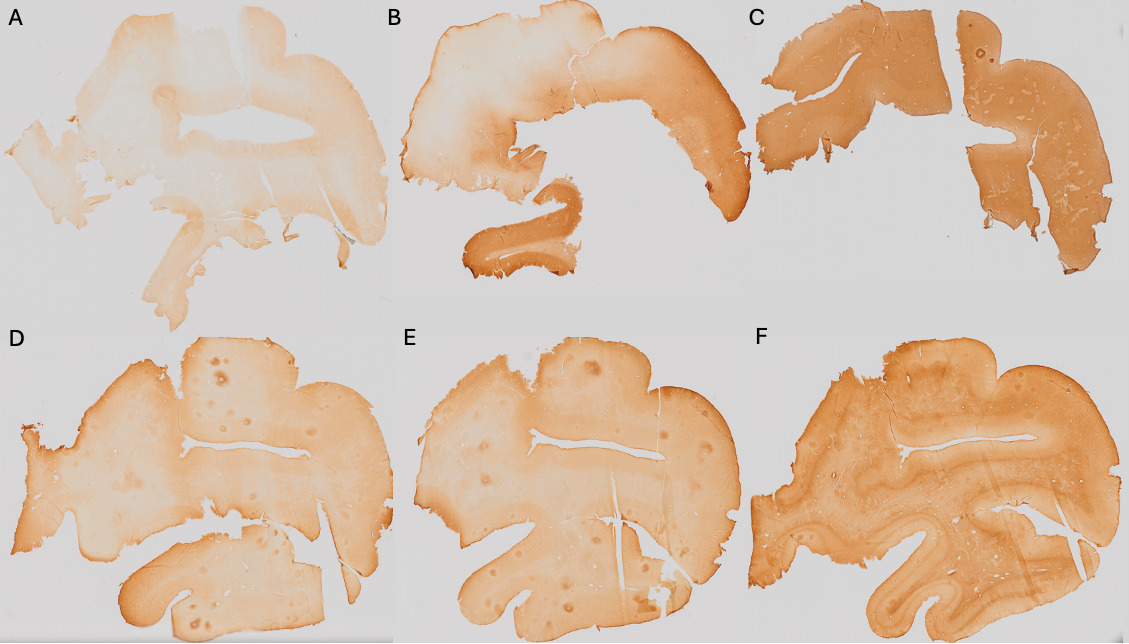

Staining intensity

Histological staining intensity of the sections was qualitatively assessed as it could impact the alignment of the tissue (i.e., if certain parts of the tissue are not sufficiently stained, then those areas could be impossible to align). Darker sections were considered of higher histological quality, since they provided clearer visualization of anatomical landmarks.

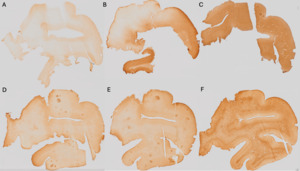

Pale=0 (Figure 1A); Heterogeneous=1 (Figure 1B); Dark=2 (Figure 1C).

Gray matter to white matter contrast

The GM-WM contrast was assessed since more contrast on the histology sections allows for better placement of markers on different boundaries of the tissue (i.e., pial surface of the GMc and GMc-to-WM boundary). A sharp GM-WM contrast reflected higher histological quality, since it provided a clearer visualization of anatomical landmarks.

No contrast=0 (Figure 1D); Blurred contrast=1 (Figure 1E); Sharp contrast=2 (Figure 1F).

Registration quality

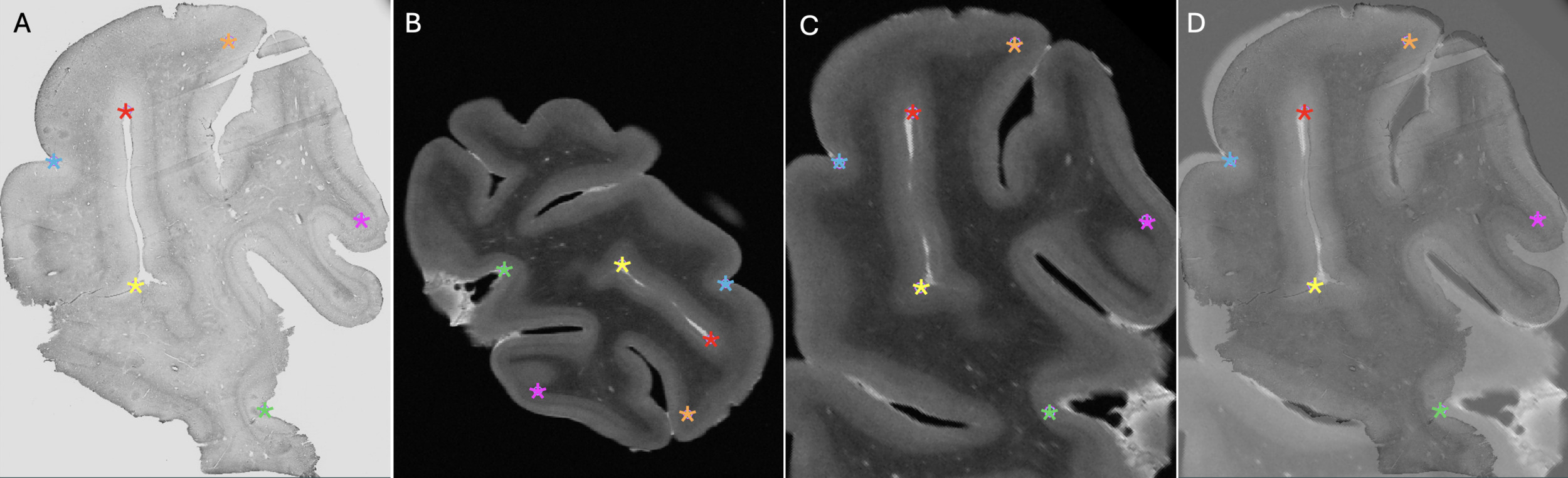

Number of tags

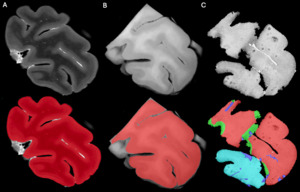

The number of tags used for manual registration was considered a variable reflecting the ease of registration. If more than 4 tags were needed (minimum to initiate manual alignment), this suggested a more complex registration. An example of the anatomical landmarks (6 tags) that were used is shown in Figure 2.

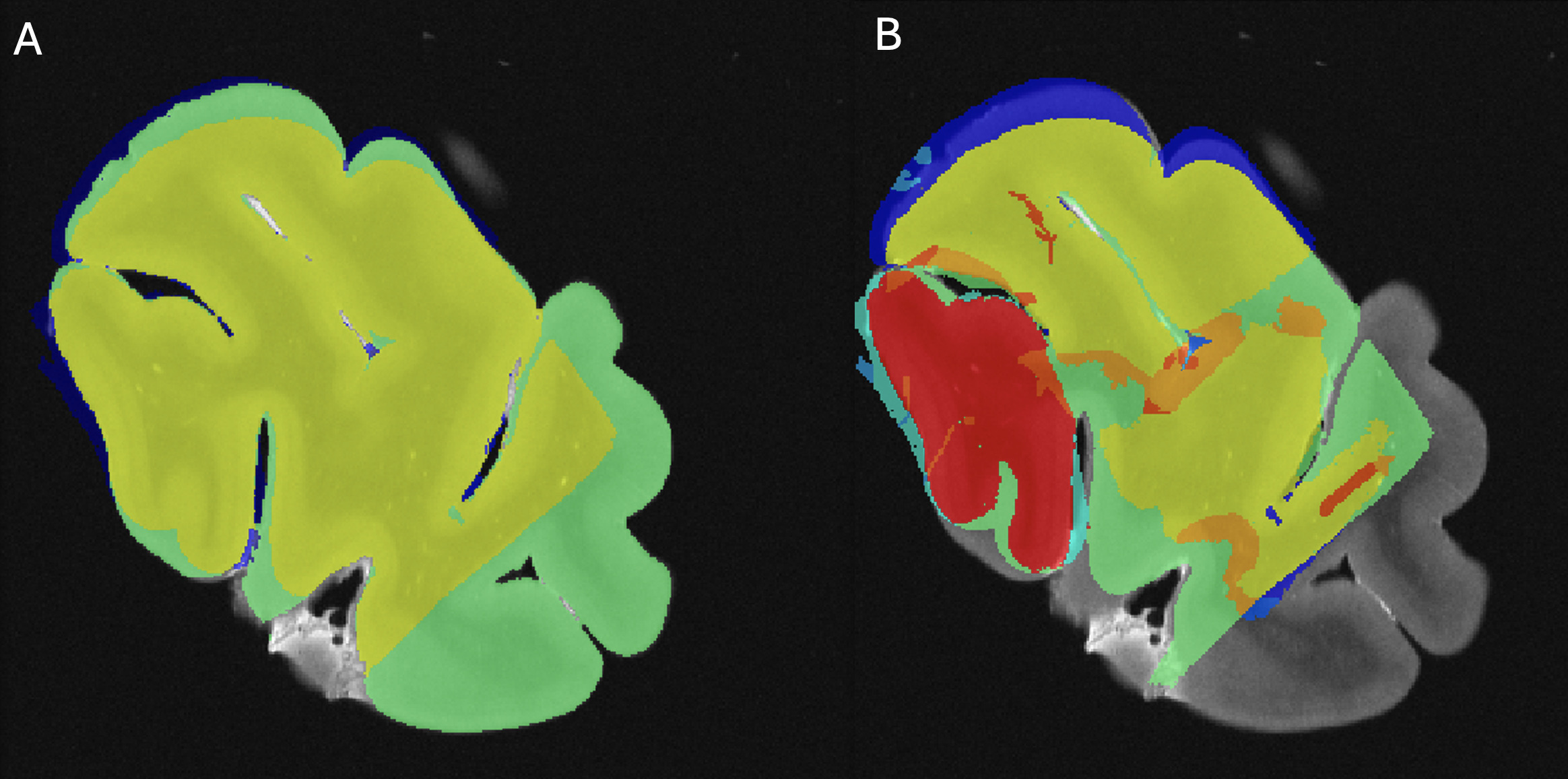

Tissue block-MRI-histology colocalization

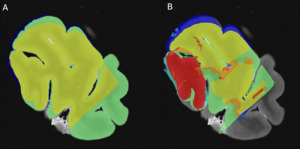

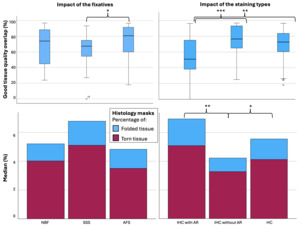

Using Display software from the MINC toolkit, we segmented the surfaces of the same level of the MRI slide (Figure 3A) and the photograph of the tissue block (Figure 3B) registered to the corresponding histology section (Figure 3C). The histology sections were segmented by an expert with more than 8 years of experience (EMF), creating the following masks: Label 1 (Red)=Non-folded/Non-torn tissue (Good quality); Label 2 (Green)=Folded tissue; Label 3 (Blue)=Torn tissue; and Label 4 (Cyan)=Non-folded/Non-torn tissue that was not parallel to the MRI plane (Good quality but off plane) (Figure 3C). The surface of each mask was calculated as number of pixels in the MRI image space by transforming the histology and tissue block images to the MRI image space using the generation transforms. The MRI and photo block masks (Figure 3A-B) were then overlapped (Figure 4A) to assess the amount of tissue that was cut from the scanned block to be able to fit the vibratome. Then, the overlap of the histology mask (Label 1, Non-folded/Non-Teared tissue) and the photo block mask (Figure 3B-C and Figure 4B) was used to assess the percentage of tissue loss in the histology sections. Dice Kappas of the overlapped masks were also calculated to assess the amount of overlap. All measurements were generated automatically using an in-house MATLAB script. The percentage of tissue showing Good quality was then compared according to the fixatives and the staining types. We also assessed the mean percentage of Folded tissue and Torn tissue for each group to assess if the quality of the histology section affected the registration quality.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables (sections ‘Staining intensity’ and ‘GM-WM contrast’) were assessed using chi-square test. Quantitative variables (sections 'Number of tags and ‘Tissue block-MRI-histology colocalization’) were assessed using Kruskal-Wallis analyses according to their distribution. All the variables were compared between the three experimental groups (NBF, SSS and AFS), as well as between the three different staining types (IHC with AR, IHC without AR and HC). All variables were also assessed individually within the comparison groups so that the variables were evaluated independently. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS statistics (version 29.0.2.0) and were adjusted for multiple comparisons following a Bonferroni correction.

Results

Histology quality

Staining intensity

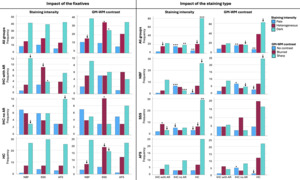

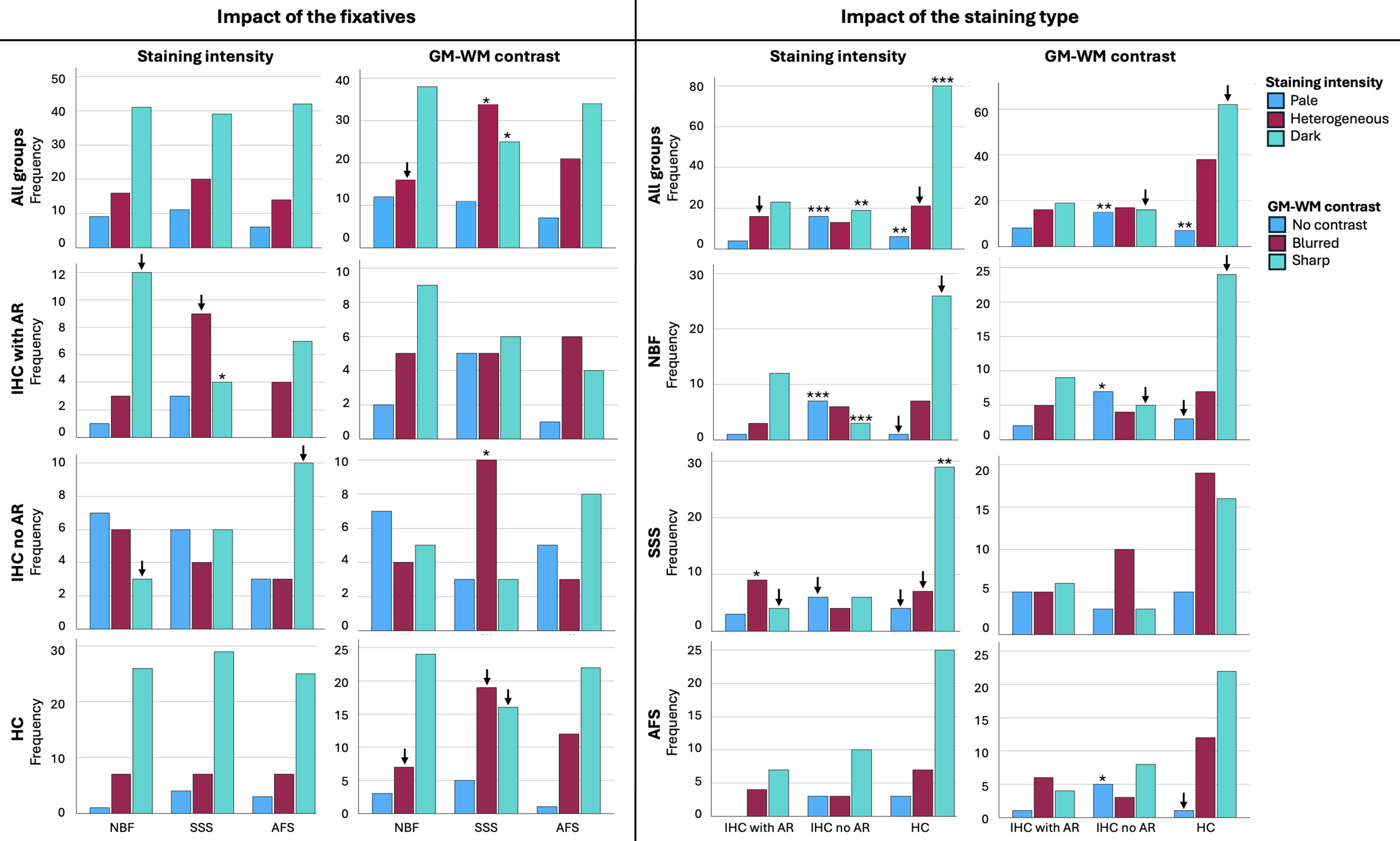

No significant difference was found in the staining intensity of the histology sections across the three fixatives (p=0.696) (Figure 5, top left). However, when considered individually, in IHC sections processed with AR, SSS-fixed brains showed a significantly lower frequency of Dark sections (p=0.0037) and a higher number of Heterogeneous sections (p=0.045), while the later did not retain significance after a Bonferroni correction. The other two staining types (IHC without AR and HC) showed the same pattern as the overall staining intensity according to the fixatives (Figure 5, left column).

According to the impact of the staining types, IHC with AR showed more sections with a heterogeneous staining intensity, but this did not retain significance after a Bonferroni correction (uncorrected p=0.04). IHC without AR showed a significantly higher number of Pale sections than with AR and HC staining (p<0.0001) and significantly fewer Dark sections (p=0.0003). Finally, HC sections showed significantly fewer Pale sections (p=0.0007) and a significantly higher number of Dark sections (p<0.0001) (Figure 5, top right). When considered individually within the fixative groups, NBF, SSS and AFS brain blocks followed the same pattern of a higher number of Dark sections in HC sections, and a higher number of Pale sections while lower number of Dark sections in IHC without AR (Figure 5, third column).

Gray matter to white matter contrast

GM-WM contrast showed significant differences between sections of blocks that were fixed with the three solutions (p=0.03). NBF-fixed blocks showed fewer sections with a Blurred contrast than the other two solutions, but this did not retain significance after a Bonferroni correction (uncorrected p=0.016). SSS-fixed blocks showed a significantly higher number of Blurred contrast (p=0.005) and significantly fewer Sharp contrast (p=0.005) than the sections fixed with the other two solutions (Figure 5, top row, second column). When considered individually, sections processed with IHC without AR showed a significantly higher number of Blurred GM-WM contrast when fixed with SSS (p=0.005), and sections processed with HC also showed more sections with Blurred contrast and fewer with Sharp contrast, but this did not retain significance after Bonferroni correction (p=0.037 and p=0.0069, respectively) (Figure 5, second column).

GM-WM contrast was also significantly affected by the staining type (p=0.001). IHC with AR did not show any statistical difference. However, IHC without AR showed significantly more sections with No contrast (p=0.0003) and fewer sections with a Sharp contrast than HC, but this did not retain significance after a Bonferroni correction (uncorrected p=0.012). Finally, HC staining showed significantly fewer sections with No contrast (p=0.0002) and more sections with Sharp contrast, but this did not retain significance after Bonferroni correction (uncorrected p=0.0069) (Figure 5, bottom right). This pattern was also observed when blocks fixed with the three fixatives were considered individually; NBF-fixed and AFS-fixed blocks processed with IHC without AR showed significantly more sections with No contrast than when processed with the other two staining types (p=0.0027 and p=0.0037, respectively) (Figure 5, fourth column).

Registration quality

Number of tags

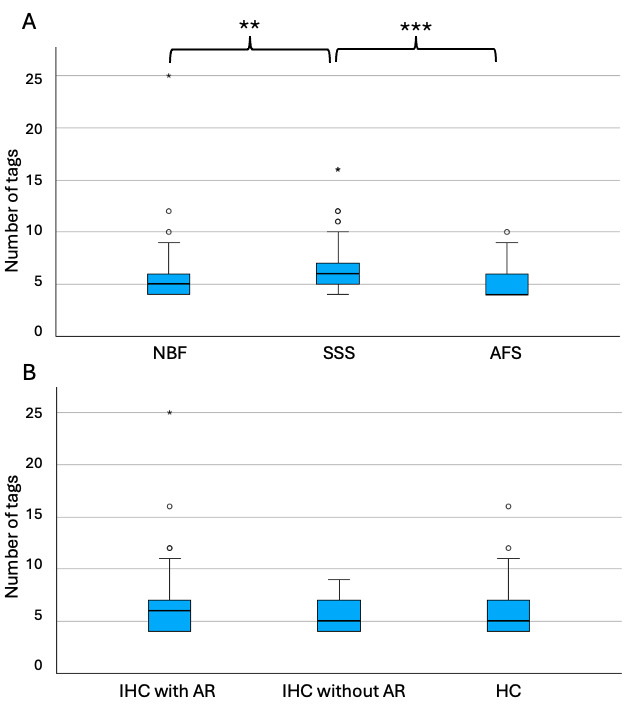

SSS-fixed blocks required significantly more tags to initiate alignment (median=6, range 4-16) than the blocks that were fixed with the other two solutions (NBF; median=5, range 4-25; p=0.002 and AFS, median=4, range 4-10; p<0.001) (Figure 6A). The staining type (IHC with AR, IHC without AR and HC) did not have an impact on the number of tags that were necessary to manually register the sections, since no significant difference (p=0.55) was found across groups (IHC-AR, median=6, range 4-25; IHC-noAR, median=5, range 4-9; HC, median=5, range 4-16) (Figure 6B).

Tissue block-MRI-histology colocalization

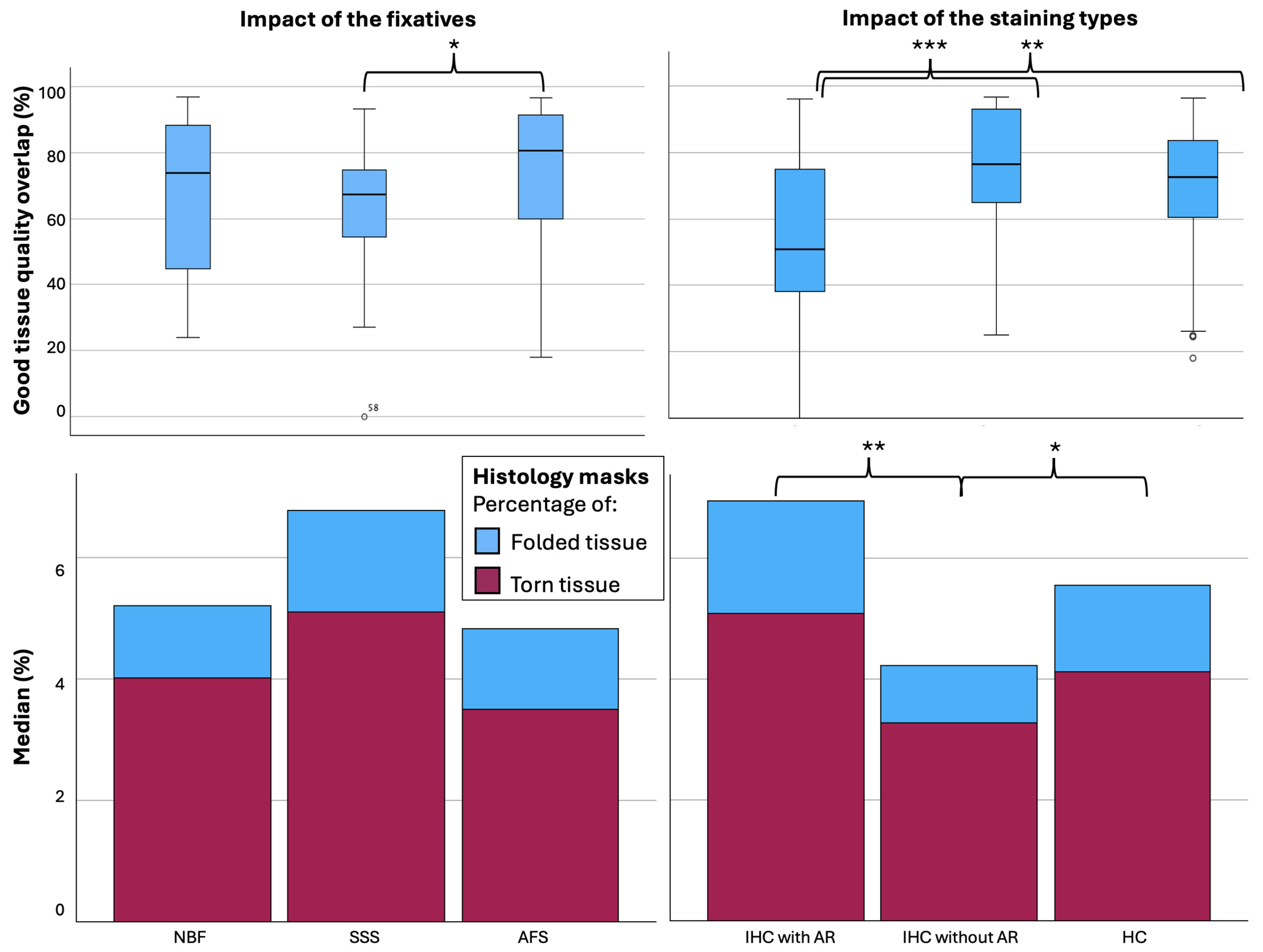

We used the overlap of the photo block and MRI (Figure 4A) as the target of the histology masks to assess the percentage of the histology sections of Good quality (label 1=Non-folded/Non-torn tissue) that colocalized with the MRIs. AFS-fixed blocks showed significantly higher overlap (%) between the MRI and Good quality histology mask (median=80.49, range 18-97, median kappa=0.892) than SSS-fixed blocks (median=67.40, range 0-93, median kappa=0.805) (p=0.012) (Figure 7 top left). Percentage of the good quality histology masks overlap with MRI and tissue block overlap were significantly different between the staining types, with a median of IHC with AR, IHC without AR and HC of 50.78 (range 0-96, median kappa=0.674), 76.45 (range 25-97, median kappa=0.841) and 72.46 (range 18-96, median kappa=0.870) respectively (p<0.001). IHC with AR histology sections showed significantly less overlap than IHC without AR (p<0.001) and HC (p=0.003) (Figure 7, top right).

We also found that there was a higher percentage of Torn tissue in the brain blocks fixed with SSS, but this did not retain significance after a Bonferroni correction (Figure 7, bottom left). The histology sections processed with IHC without AR (median=3.24, range 0.82-23.60) showed significantly less Folded tissue than sections processed with HC (median=4.13, range 0-25.57, p=0.027) and with IHC with AR (median=5.08, range=1.35-71.40, p=0.004) (Figure 7, bottom right).

Discussion

This study aimed to describe the quality of linear registration between histology sections and MRI in human brain blocks fixed with three solutions, and in histology sections that were processed with different staining types to provide new insights on registration protocols of brain blocks from gross anatomy laboratories.

Histology quality

Staining intensity

Since we had previously found slight differences in the background staining intensity of mice brains fixed with SSS,9 we assessed intensity of the background staining on a scale of pale to dark. Although we acknowledge that higher staining intensity does not always reflect good histological quality, we assessed staining intensity as it could impact the visibility of anatomical landmarks on the histology sections, consequently affecting the registration quality; it was not intended as a measure of cell preservation. In microscopic cellular assessment, an increased staining intensity would not be ideal since it hides the contrast between cells and the background. However, for registration purposes, there is a degree of staining intensity that must be dark enough to allow for landmark visualization to place the tags but also pale enough to still see the contrast with the cells for further biological analysis. Here, we found a higher frequency of Dark sections (which helps the rater placing the tags for the manual linear registration to decide on the landmarks that will be selected) in the blocks fixed with the three solutions, reflecting no impact of the chemical composition of the different solutions on the staining background when considered altogether (Figure 5, top left). However, SSS-fixed brains showed a higher number of Heterogeneous sections and lower Dark sections when processed with IHC with AR, while more Pale sections were also observed when processed with IHC without AR in these cases. Therefore, staining intensity of immunohistochemistry procedures seems to be affected more in SSS samples. This is in accordance with the fact that SSS-fixed brains showed less homogeneous distribution of the antigens of interest (perhaps less staining intensity) in our previous study.10

Furthermore, the staining intensity seems to be affected by the staining type. Indeed, HC showed significantly more Dark sections, which was expected as our previous assessments had also shown strong labeling and no impact of fixative.10 Furthermore, antigenicity preservation (and therefore staining intensity) was not homogeneous between the antibodies and the fixatives.10 Our results showed that IHC without AR have significantly more sections with both pale and dark backgrounds, especially when fixed with NBF, while IHC with AR showed more Heterogeneous sections, especially when fixed with SSS. This could be caused by the fact that AR increases antigen staining but also may decrease in some cases non-specific background labeling.10,35–37

Gray matter to white matter contrast

Gray to white matter contrast was also assessed since it could have an impact on the chosen landmarks and therefore on the registration quality. We found that SSS-fixed brain blocks showed a higher number of sections with Blurred contrast compared to the other solutions, especially when they were processed with IHC without an antigen retrieval protocol. This was consistent with our previous observations showing a slightly lower contrast of the MRIs in SSS-fixed brains.12 This is also consistent with previous findings in histochemical sections where SSS-fixed brains showed paler neurons in Cresyl violet stain, heterogeneous fibers in Luxol fast blue, and lower quality in Bielschowsky’s staining, as well as lower antigenicity distribution without AR.10 GM-WM contrast was also affected by the staining type, where IHC without AR showed more sections without contrast. Again, this is because AR increases the labeling of the cells and therefore shows a higher differentiation between gray and white matter layers, otherwise this is lacking when no antigen retrieval is applied to the procedure.

Registration quality

The number of tags that were used to manually register the T2-TurboRARE sequence with histology sections was significantly different in the brains fixed with the three solutions. AFS and NBF-fixed blocks required fewer tags than the SSS-fixed blocks, reflecting a more difficult registration with the latter. This is consistent with our previous findings that SSS-fixed tissue is more friable and difficult to manipulate than the other fixatives, resulting in more tears and folding of the tissue,10 and therefore more distortions compared to the MRI sections. This is also supported by our quantitative analysis of the percentage of Good quality tissue masks, where we found that SSS-fixed blocks showed less overlap with the tissue block masks than AFS-fixed sections, and that a higher percentage of Torn tissue was found in the SSS-fixed brains. Although this latter statement did not retain statistical significance, it was again consistent with previous qualitative findings of our team.10

Regarding the relation between registration quality and the staining types, we found no difference in the number of tags required to initiate manual alignment between the three solutions. However, we found a higher Good tissue quality overlap and less Folded and Torn tissue in the histology sections that were processed with IHC without an antigen retrieval protocol. Indeed, we expected that it would be more difficult to register the sections when an AR protocol was conducted prior to IHC since it is known to enhance tissue tearing and tissue loss.10,38 However, AR staining being darker (higher contrast with the cells which resulted in a higher GM-WM contrast), it was unexpectedly easy to put the tags in most cases, since it enhanced the visibility of the landmarks. Therefore, we suggest using an AR protocol in IHC even if this results in a more difficult manipulation of the sections, since it also results in a better staining and therefore, better correlates with MRI findings.

Groups of comparison

Fixatives

Immersion of freshly extracted brains in 10% NBF is a ubiquitous fixation protocol in brain banks.8,34 This is currently coined as the control group since neuroscientific findings have been made with these brains so far. However, NBF solution is not ideal for anatomy dissection and also show inconveniences in histology and MRIs since the surface of the brain shows signs of over-fixation, while the deep white matter and nucleus is more poorly preserved.39,40 Furthermore, brain banks offer very few and small tissue samples to researchers, so we suggest that brains from anatomy laboratories may be used as an alternative. Moreover, perfusion fixation with NBF is feasible,41 and can be combined with perfusing the rest of the body with another solution.42 This would allow the adequate preparation of cadaveric specimens for gross dissection and surgical training along with optimal brain preservation for histochemical and immunohistochemical processing. However, practices in multiple anatomy laboratories are not yet ideal and use AFS and SSS as alternatives.

Our results support that AFS provides a good alternative for fixation, since it preserves brain MRI contrasts,11,12 histology quality and manual registration of both modalities in a good manner, as well as for combining gross anatomy dissection and histology assessment of different tissues.43–50

Conversely, SSS-fixed brains are of lesser quality, impacting the registration of MRI and histology images, although still feasible and of sufficient quality. These brain blocks require greater care in manipulation and histology protocols to achieve registration results closer to those obtained with the other two solutions. This is probably due to the lower amount of formaldehyde in its formulation,51 leading to a poorer preservation of the tissue integrity, as explained in our previous findings.10

Staining type

IHC without AR group included the 4 labeled sections per specimen (NeuN, GFAP, Iba1 and PLP) that did not go through an AR procedure, while IHC with AR did. We decided to separate these two groups since we considered that heat-induced antigen retrieval could impact: 1-GM-WM contrast and staining intensity and 2-tears and folding of the tissue as we observed in a previous study of our group.10 Furthermore, we chose to include 4 IHC stains (NeuN, GFAP, Iba1, and PLP) to label the main brain cell populations (i.e., neurons, astrocytes, microglia and myelin), which are commonly used in histopathology diagnosis, using protocols already validated for the three solutions in our previous study, which made this new assessment more robust.10

The HC protocols included the two levels of sections using five different stains (i.e., ten slices per specimen), to label: 1) the endoplasmic reticulum and cellular nuclei, which stained cell bodies of neurons and glial cells, using a Cresyl Violet and a Neutral red staining52; 2) the myelin of oligodendrocytes using Luxol Fast Blue,53 frequently used in multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease or cerebrovascular diseases17,24,26–28,30–32,54–56; 3) the ferric iron aggregation in the neuropil of the brain, using a Prussian blue staining (Perl’s stain),57–59 commonly used in different white matter pathologies detected by MRI, or again, neurodegenerative diseases28,60–64; 4) the nerve fibers and neurofibrils using Bielschowsky’s silver staining method,65 used typically to demonstrate axonal tangles and senile plaques,66–73 and 5) the cell bodies and small capillaries using H&E staining, the most common histopathological stain used in diagnosis of neuropathology.26,27,29,54,61,72,74–76 HC stains seem generally more robust than IHC, giving the highest staining intensity and sharpest GM-WM contrast. This can be related to the fact that antigens and epitopes recognition, which can be modified by cross-linking of the proteins related to chemical fixation, is not involved in these HC staining protocols.

Limitations

We acknowledge that this study was conducted with a small convenience sample. Therefore, all statistical results should be mostly considered as descriptively informative. Nonetheless, while there were only 4 blocks per fixative, this resulted in 9 stains per blocks * 12 = 120 stains and their subsequent registrations. The samples were heterogeneous in terms of the cause of death, the post-mortem delay, and the cortical area; however, we always took neocortex and subcortical WM for all the blocks. The use of this heterogeneous sample may be seen as a disadvantage by most, since the control of as many variables as possible is what is generally desired when designing an experiment. However, we consider this heterogeneity as an advantage for the general scope of our research, which is the assessment of MRI and histology feasibility in specimens of unpredictable characteristics, since we have no control on the comorbidities, causes of death, etc. of the donors that arrive to anatomy laboratories. So, this study shows that even in different circumstances and with various confounding variables, which could affect the tissue quality, registration between histology and MRI is still feasible. Finally, the small sample size resulted in heterogeneous groups of comparison regarding the staining types. It is not possible to know the impact of each antigen of interest (NeuN, GFAP, Iba1 and PLP) considered individually since they were included in the same staining type. Another limitation of this study is that our blocks were too large to be cut as they were scanned (we had to trim them to fit them in the vibratome). This resulted in an impossible direct comparison on tissue loss and colocalization between the histology and MRIs. However, we tried to overcome this issue by segmenting masks of the photographs of the tissue blocks after being trimmed, of the MRIs, and of the histology to facilitate the comparisons. Finally, we also had to deal with sections that showed Good histology results but that were off plane (Label 4 of the masks), which resulted in poor registration quality (high number of tags) since they were not cut parallel to the MRI scans (i.e., poorer orientation of the flat surface of the block on top of the lid while scanning). However, this is not a problem related to the fixative groups or the staining type, but it could have impacted the overall results. This problem could be resolved in future studies by applying an automatic nonlinear registration to the histology-MRI manual registration (Note: our in-house pipelines for automatic nonlinear registration are still under development).

Conclusion

We conclude that brain blocks fixed with solutions used in gross anatomy laboratories, preferably an AFS, may be used for manual linear registration of histology photomicrographs and high-resolution MRIs of the blocks, allowing to take advantage of the two most common neuroimaging modalities. This is promising for neuroscientists interested in using larger brain samples from anatomy laboratories to correlate histology findings with MRI and possibly increase knowledge on biomarkers of normal aging or neurodegenerative disease in post-mortem diagnosis.

Data and Code Availability

We have used the MINC ToolKit developed by the Brain Imaging Center of the Montreal Neurological Institute (McGill University) which is publicly available at: https://bic-mni.github.io.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the generosity of the body donors and their families for making our projects possible. We also acknowledge funding resources and the anatomy laboratory staff of the UQTR for their support and help at the lab. We would also like to thank the Cerebral Imaging Center staff (at the microscopy platform and Roqaie Moqadam) who helped in tissue management.

Funding Sources

All authors are funded by the Government of Canada, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no competing interests